One reason so many are quitting: We want control over our lives again

The pandemic, and the challenges of balancing life and work during it, have stripped us of agency. Resigning is one way of regaining a sense…

Thought Leader: Amy Cuddy

After Beijing used restrictions on rare earth magnet exports to shut down Ford auto plants and force Trump to stand down in his tariff war with China, reducing America’s minerals dependencies have been a fixation in Washington. The Pentagon signed a very generous deal with America’s only rare earth mining firm, MP Materials, giving the government an equity stake in the firm and guaranteeing it would buy minerals from the company at a price far above market value. U.S. officials are looking for more deals in the rare earth space.

Concern about “critical minerals” has shot upward in recent years as China has monopolized supply, largely in the midstream processing steps. Parts of the critical mineral debate are new. Electrification plus advanced manufacturing have driven up world demand for minerals from graphite to ruthenium.

Yet the mixing of resources and political competition is not new. Several years ago, I read a fascinating dissertation by Rob Konkel titled “Building Blocs: Raw Materials and the Global Economy in the Age of Disequilibrium.” I dug back into Konkel’s dissertation amid the rare earth crisis this spring and found the parallels even more striking now. Here are my notes.

Steel required iron ore and coal, of course. But metallurgists quickly realized that adding other materials to steel could make steel harder or allow it to withstand higher temperatures. Manganese, chromium, nickel, tungsten, and other metals were soon being added to steel to deliver better properties. Konkel calls this the “age of alloy steel”—meaning that industrial powers needed not only iron and coal, but these other materials too.

This presented challenges for the world’s steel powers, because they often lacked deposits of these niche metals. “The mighty Americans were not self sufficient,” Konkel notes. “The most critical shortages were the ferro-alloying minerals, like manganese, tungsten, and chrome. But there were several other minerals which did not reside within the United States’ borders, like tin, mica, graphite, mercury, antimony, and nickel.” If the U.S. were to lose access, one analyst warned, it would return to “horse and buggy days.” Now, like then, the auto industry was a critical source of demand for niche minerals.

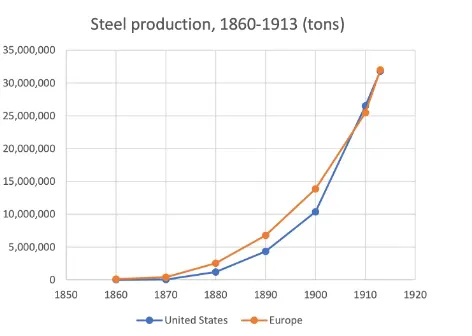

The U.S. wasn’t alone in having lots of steel but comparatively few alloying materials. “The four leading steelmaking countries in the world,” Konkel writes, “the United States, Great Britain, Germany, and France—accounted for 90 percent of the world’s steel production, but perhaps only 1 to 2 percent of the world’s manganese.” Most of the world’s manganese in 1913 came either from India, then part of the British Empire, or from a mine in present-day Georgia, then the Russian Empire but soon the Soviet Union. That was a whole lot of what today would be called “political risk.”

Tungsten presented similar challenges. “Over half the world’s tungsten was mined by hand in the Chinese provinces of Hunan and Jiangxi. There were other significant deposits in Burma and Bolivia. Across the entire North American continent there were only small deposits that were highly expensive to produce. Germany was worst off, Konkel writes, importing “practically 100 percent of its chrome and tungsten ore requirements.”

World War I drove a surge in demand for these alloy metals, and a scramble to secure supply. U.S. mineral imports surged over the course of the war, partly driven by higher volumes, partly by higher prices. U.S. tungsten prices increased from $750 in 1913 to a peak of $10,000. Higher prices drove up domestic production, making some previously non-viable projects economical. But imports shot upward, too, because domestic geology couldn’t support the voracious needs of American industry.

Yet geology wasn’t everything. Processing mattered too. And processing, the allied powers discovered in World War I, was disproportionately concentrated in Germany. Before the war, Germany’s geological deficits had driven its traders to scour the world for supply. They’d bought mines across the world and built processing supply chains. Konkel writes:

Shortly after the war began, British officials discovered the embarrassing situation in which the Empire produced about half of the world’s tungsten ore but British industry depended wholly upon Germany not only for ferrotungsten, but for many of its tungsten steel cutting tools. German manufacturers crafted their industrial tools with tungsten ore sourced from the British Empire, especially Burma. Prior to the war, there were British attempts to produce ferrotungsten commercially, but they proved unable to compete. At the time, this was a disappointment—after the war began, it became a dire threat to Britain’s war-making capacity.

Australia—part of the British Empire—was the world’s second largest zinc producer, but German firms controlled its output. The Germans were expropriated when World War I began, but that didn’t solve the problem:

Though the Enemy Contracts Annulment Act expropriated the German firms of their Australian possessions, doing so destroyed the channels through which Australian ores found their market. Typically, the [German] Zinc Trio funneled the ores to European smelters, which they also controlled. Germany had effectively captured the main smelting outlets for Australian minerals, especially after invading Belgium. So while the Australian government had turned the country’s zinc over to nationals, their primary markets had been foreclosed—and there did not exist capacity elsewhere to absorb the output.

The same problem was present in tungsten:

Before the war, the European tungsten market resided in Hamburg, where more than 2000 tons of concentrated ore was sold annually. This was remarkable, considering Germany produced, at best, one percent of the world’s tungsten ore. Indeed, most of the world’s tungsten ore was being mined in parts of the British Empire, but more than half of global production found its way…to Hamburg, where it was either smelted and sold to Britain as a more expensive refined product (ferrotungsten) or used to make high-speed steel cutting tools.

Before the war this had seemed like a commercial vulnerability. In 1914 it became a military crisis. The UK needed an entire year before it could smelt its own tungsten. The Allies called this network of German metal trading companies “the octopus.” It took the full force of wartime economics to unwind it.

After World War I ended, the importance of these alloys was clear. But the shift to a civilian economy removed the willingness to pay any price, making some wartime projects non-viable. The depression-era slump in steel demand pushed prices down further, intensifying this dilemma. Diversifying supply sounded good in theory. But who was willing to pay? Some miners preferred to find cheaper but less reliable suppliers. The search for manganese led Averell Harriman to venture into the Soviet Caucasus to buy the Georgian manganese mine.

As World War II wound down, solving the minerals problem was a postwar priority. The U.S. and other powers built stockpiles and took other steps to guarantee supply. Yet the primary strategy was to use American power to guarantee open markets for minerals and secure trade routes. Minerals were just as “critical” to the world economy in the postwar period, but American power guaranteed their supply. The German “octopus” was replaced by a Western octopus—the network commodity traders based in New York, London, and Switzerland, all of whom depended on the U.S. financial system.

Now this has partially reversed. Western commodity traders’ power, at least when it comes to certain niche metals. Germany’s near-monopoly on tungsten smelting in the 1910s has been replaced by China’s monopoly on rare earth processing today. Konkel argues that “the Pax Americana was the resolution to the interwar raw materials problem.”

So we shouldn’t be surprised that the demise of the Pax Americana has coincided with the re-emergence of the minerals dilemma.

Professor Chris Miller is a geopolitical expert who talks about the origin, impact, and future of AI. He is the author of Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology, a book that explains how computer chips have made the modern world—and how the U.S. and China are struggling for control over this fundamental technology. Chip War won Financial Times’ Best Business Book of the Year award. Breaking down the motives behind international politics and economics in a thoughtful and concise manner, Miller provides audiences with fresh, alternative perspectives and leaves them wanting to know more. Contact WWSG to host him at your next event.

One reason so many are quitting: We want control over our lives again

The pandemic, and the challenges of balancing life and work during it, have stripped us of agency. Resigning is one way of regaining a sense…

Thought Leader: Amy Cuddy

Scott Gottlieb: How well can AI chatbots mimic doctors in a treatment setting?

This is an Op-ed by WWSG exclusive thought leader, Dr. Scott Gottlieb. Many consumers and medical providers are turning to chatbots, powered by large language…

Thought Leader: Scott Gottlieb

Sara Fischer: The AI-generated disinformation dystopia that wasn’t

This piece is by WWSG exclusive thought leader, Sara Fischer. Amid the craziest news cycle in recent memory, AI-generated deepfakes have yet to become the huge truth…

Thought Leader: Sara Fischer