Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

As word circulated late last year that Stephen Harper, Canada’s 22nd Prime Minister, was planning to launch an activist investing fund with a protégé of Wall Street raider Carl Icahn, some eyebrows were raised on Bay Street and in political circles.

While former prime ministers have not shied away from private sector work after their time at 24 Sussex (if they leave politics at all, that is) in most cases that involvement has come through cushy positions at blue chip law firms, where drumming up business and making introductions at home and abroad has been the order of the day.

The rough-and-tumble world of activist investing, in which outsiders target underperforming companies and take stakes in them while sometimes less-than-gently encouraging a change in direction, would seem to be a deeper and more hands-on venture into the corporate realm than most have attempted.

But the prospect of a former prime minister shaking things up in corporate boardrooms may not be as jarring when one considers Harper’s political legacy. Trained as an economist, Harper was instrumental in upending Canadian politics through the formation of the right-wing Reform Party and later helped unite the country’s sharply divided conservative political factions. When it came to governing, he actively courted business leaders to his team, including recruiting Onex Corp. managing director Nigel Wright to become his chief of staff.

“Harper was, in the best sense of the word, an activist as Prime Minister,” said Karl Moore, associate professor of strategy and organization at McGill University’s Desautels Faculty of Management, adding that he never pulled back from his vision to reshape the country.

“Activist investors have done some good things, and a few not so good to shake things up … and one could argue Stephen Harper did that as Prime Minister.”

As in most matters, Harper has in his post-prime-ministerial life refused to follow too neatly in the footsteps of his predecessors, Liberal or Conservative.

Some, like Paul Martin, who was wealthy before going into public life — having run and then purchased shipping company CSL Group Inc. — occupied their time out of office with projects of personal interest. Martin, for example, became involved in a number of educational and entrepreneurship initiatives for indigenous communities and advised the African Development Bank.

Brian Mulroney returned to law firm Ogilvy Renault, now part of Norton Rose Fulbright, after his run as Canada’s 18th Prime Minister. Before his life in politics, Mulroney had also served as president of the Iron Ore Company of Canada, and afterwards he took up seats on the boards of companies including Barrick Gold Corp., Quebecor Inc. and Archer Daniels Midland Co. (ADM).

John Turner and Jean Chrétien, too, returned to the law. Turner joined Miller Thomson LLP, while Chrétien became counsel for Heenan Blaikie LLP and later Dentons Canada. Chrétien also became involved in international organizations dedicated to democracy, peace and solving problems facing the global community.

Following his government’s defeat in 2015, Harper established a private consultancy called Harper & Associate in partnership with his former chief of staff Ray Novak. Upon leaving politics, Harper — who had become heavily associated with western Canada after moving from Toronto to Calgary, where he earned a Master’s degree in economics — worked out of the Calgary office of international law firm Denton’s, where he advised clients on market access and managing global geopolitical and economic risk.

According to a 2018 article in Maclean’s magazine, his pitch included a pledge to help clients navigate international waters — with the calling card that Harper’s Conservative government had reached several overseas trade deals without public backlash.

In contrast with many of other former prime ministers, he also went on to become directly involved in a handful of corporate ventures, mostly with an investment focus.

Among them is AWZ Ventures, a Canadian private investment company that invests in Israeli cybersecurity, intelligence and security technology. Harper is a partner and president of the advisory committee at the firm, whose website boasts management and advisors including former directors and senior executives from global security and intelligence agencies such as Mossad, the CIA, FBI, MI5 and CSIS.

Harper is also an adviser to 8VC, a San Francisco-based venture capital firm that aims to partner with founders and entrepreneurs to build “transformative” technology platforms, and whose managing partner, Joe Lonsdale, was an early institutional investor in Oculus, a virtual reality platform later acquired by Facebook/Meta, and a co-founder of Palantir, a sometimes controversial data-mining software company.

Closer to home, Harper became a director at Toronto-based real estate firm Colliers International, a global leader in real estate services and investment management with operations in 65 countries and $4 billion in annual revenue.

Ed Waitzer, a former chair of Bay Street law firm Stikeman Elliott LLP, who is an investor in AWZ and did legal business with Colliers over the years, said Harper has proven himself to be “excellent” as a director and adviser.

“While we may differ on policy issues, I find him thoughtful, diligent and strategic,” Waitzer said, noting that their paths crossed previously when Harper was in government and Waitzer was involved in initiatives to create a national securities regulator and strengthen business ties between Canada and Chile.

In their dealings, Waitzer said, Harper has brought “experience, judgment and ability to deal with people (through skills) gained from earlier parts of his career.”

Former politicians, and particularly highly placed ones such as country leaders, are typically retained because they bring access to prospective investors or investment opportunities, and credibility.

“Good ones also bring a unique perspective and good judgment,” Waitzer said.

Harper could be brash while in office, pushing hard for pipelines and energy development, curtailing media access and heavily scrutinizing charities, including funding an audit crackdown by tax authorities.

But courting controversy is not uncommon in public office and it is unlikely to get in the way of good business in life after politics, said Waitzer, who retired from Stikeman last year.

“Any public figure worth his/her salt has baggage. If not, it means they never took a stand on issues worth fighting about.”

Waitzer said Harper will undoubtedly “add value” to his latest venture in activist investing with partner Courtney Mather, a former portfolio manger at Carl Icahn’s investment fund manager Icahn Capital — if they get the firm up and running as planned.

According to a Bloomberg News report, the firm is to be called Vision One, and the intent is to target mid-sized companies — including those in the consumer and industrial sectors — in which they could unlock value through governance improvements, among other changes.

Harper would be chairman and Mather, whose professional designations in chartered alternative investment analysis, financial analysis, and financial risk management, would serve as chief executive and chief investment officer.

Educated at Rutgers and the U.S. Naval Academy, Mather spent more than a decade at Goldman Sachs & Co., from 1998 to 2012, where he became the managing director for private distressed trading and investing and was responsible for finding investment opportunities for both Goldman Sachs and the firm’s clients. He has also served on the boards of Newell Brands and Caesars Entertainment.

Nigel Wright, senior managing director of Onex who was a high-profile hire as Harper’s chief of staff in 2010, said in an email from Onex’s London office that he had been told about Harper and Mather’s investment venture and provided materials. Wright said he did not feel comfortable discussing the plans unless the principals — neither of whom responded to requests for comment from the Financial Post — were ready to elaborate.

In April, Reuters reported that activist investors pushing for boardroom changes were outperforming broader market, with smaller players and upstarts such as Ancora Alternatives and Honest Capital LLC ringing up double-digit gains.

But getting established isn’t the easiest path, even for investment industry stars.

Jim Keohane, a former senior pension executive and adviser, recalled one such senior pension executive who tried to start his own fund in 2008 but returned to the pension world when he was unable to raise sufficient funds.

“He had a very strong track record and was unable to secure funding, Keohane recalled.

Not only are activist funds capital intensive but they are competitive, he said, noting that large funds such as The Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and other Canadian pensions heavyweights are already set up with dedicated in-house teams and pools of capital to take meaningful positions in companies whose boards and managers they seek to influence.

“It will be very challenging to get this off the ground,” he said, though he added that Harper’s former job as Prime Minister of Canada — and his reputation from that time — will undoubtedly be a draw for some.

“I would say that he has strong business acumen. I am sure that a lot of people would take a meeting with them because they would be interested in hearing Mr. Harper’s views.”

Harper’s ties to the business world were evident throughout his time in public office.

Though most Canadian prime ministers have tapped the business community to some extent for advisers, Harper made a decisive move early in his nearly decade-long tenure that began in 2006 by plucking high-profile executives to join his party — even courting controversy to do so.

“Mr. Harper went out of his way to recruit David Emerson, former CEO of various enterprises, and Michael Fortier, (a Bay Street lawyer and investment banker at Toronto-Dominion Bank) in the financial industry, into his early cabinet,” said Ian Brodie, another former chief of staff to Harper and now undergraduate program director in the department of political science at the University of Calgary.

Fortier served as the minister of both public works and government services and international trade, while Emerson served as trade and foreign affairs minister.

Neither political ally was easily attained.

“Emerson was poached from the Liberal caucus and Fortier was appointed to the Senate in order to let him sit in cabinet,” noted Brodie.

The Senate appointment was a rarity and was therefore somewhat controversial, while Emerson’s appointment led to a conflict of interest and ethics inquiry, which found no wrongdoing.

Moore, who has lived and taught in the United Kingdom and the United States, said there is an uneasy relationship between the public and private sectors in Canada that doesn’t exist elsewhere.

“The back and forth between government and business does not happen in Canada the way it does in the U.S. and U.K.,” he said. “There’s something where government is suspicious of business, and business is suspicious of government.”

There are some notable exceptions, such as Bill Morneau, who served as Justin Trudeau’s finance minister for nearly five years after running human resources consulting firm Morneau Shepell for a couple of decades.

That typical Canadian reticence was also not evident when Harper tapped Wright in 2010, then a senior executive at successful private equity firm Onex, as his chief of staff. Onex has been known for decades as one of Canada’s most successful buyout firms, with an international profile and $47 billion in assets under management.

Jack Mintz, chair of Alberta Economic Recovery Council — whose members include Harper and which was created to provide insight and expert advice on how to protect jobs during the economic crisis stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic and the recent collapse in energy prices — said Harper was always focussed on the international stage and did not pay particular attention to the line between the public and private sectors when building his team in government.

“Nigel is extremely smart and actually he was really an excellent Chief of Staff,” said Mintz.

“And he was looking for a big change.”

Harper was relatively young when he became Prime Minister, and still in his mid-fifties when he left politics, Mintz noted, adding that it’s not usual for Canadian politicians to seek “life after office.”

Now 62, he is looking to make his mark in perhaps the biggest way since his near-decade as Canada’s leader.

“After he stepped down as Prime Minister we had lunch together and I remember he told me his big focus was on doing international work, he didn’t want to really focus on Canada,” Mintz said.

“I think he wanted to maybe sprout his wings.”

Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

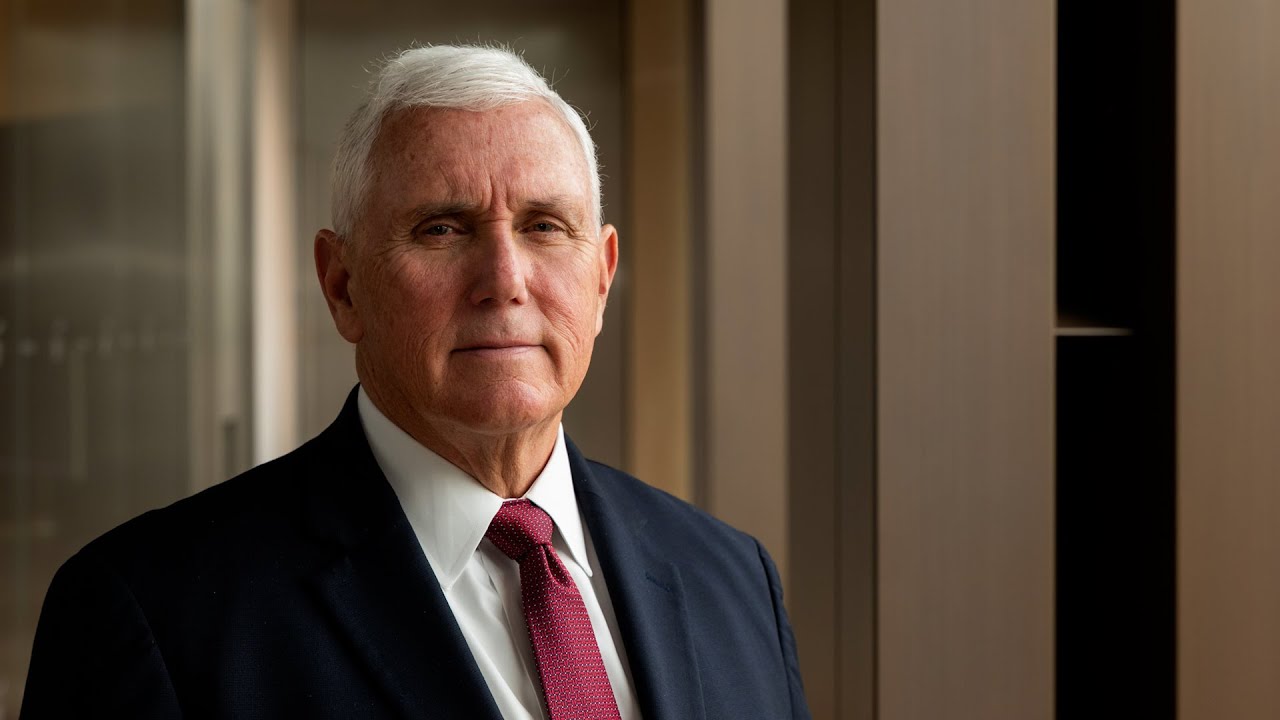

Mike Pence on U.S. Leadership and Global Strategy

Former Vice President of the United States, Mike Pence, shares his thoughts about President Trump’s framework on trying to acquire Greenland, and discusses what he…

Thought Leader: Mike Pence

Barbara Corcoran on Why Most Entrepreneurs Fail

Shark Tank star and real estate mogul Barbara Corcoran shares her unfiltered advice on entrepreneurship, investing, and building long-term success. Corcoran explains how she evaluates…

Thought Leader: Barbara Corcoran