I grew up in Morelos, Mexico, with four siblings. My parents were well educated and open-minded. Still, gaps existed. One afternoon, in 1976, when I was ten years old, my father returned from work with a volume of Jacques Cousteau’s iconic book, The Ocean World, and proudly presented it to my brother. I yearned for that book just as much as I yearned for my father’s validation. When my brother got bored with it, I snuck into his bedroom to explore its pages. Even as a child, I understood the underlying message of this experience: the ocean and its vast trove of mysteries was for men.

I was the one who was fascinated by the ocean, and this fact was lost on my father. I was also the one who, against societal expectations for a middle-class Mexican woman in the eighties, pursued an education as a marine scientist. I then became an underwater photographer for National Geographic, immigrated to two countries, and founded an influential ocean conservation organization. What if my father had recognized my passion and potential and had understood what it would have meant for me to be the one receiving that special book?

And I was one of the lucky ones. As the planet’s economic and geopolitical systems continue to destabilize under the combined weight of a pandemic, climate disruption, and fascism, women of color are far more likely to suffer the impacts of environmental distress, earlier, and more violently. These women, who struggle to pay rent, survive police brutality, and avoid deportation, all while dealing with a deadly virus, don’t have the luxury to think about solving the planet’s big environmental issues.

What if more young women of all races were empowered to participate and take charge of innovative solutions for climate change and social justice? On the flip side, what if young women never get the chance to receive an education, choose their reproductive futures, and become leaders, business owners, and scientists? As the global ship sinks, do we want the whole crew bailing out the boat or just the men?

This year’s explosive Black Lives Matter movement tore through the thin veneer shrouding America’s—and the rest of the planet’s—systemic racism towards people of color. Alongside it came the clear message that climate change and racial justice are fundamentally intertwined. Climate change affects black and brown people disproportionately, but it also concerns them disproportionately, with 57 of black Americans and 70 percent of Latinx vs. only 49 percent of whites, according to a study from the Yale Program on Climate Change. Those disproportionate effects—everything from a lack of economic advancement to mental illness—are further compounded for women in those marginalized communities; women without the freedom or opportunity to become environmental champions.

I’ve met them at home and in my travels: the street vendor with five hungry children; the destitute fishmonger up since 3 a.m.; the young girl who walks several miles each day to fetch clean drinking water for her family instead of attending school. Poor, overworked, and undereducated, it’s a heartbreaking truth that many women cannot afford to worry about much more than where their next meal is coming from.

Even as Kamala Harris, a woman of color and the daughter of immigrants, rises to one of the highest positions of power in the world, a climate change-fueled virus has set women back decades in their gains to achieve equality in the global labor force. COVID-19 aside, the World Economic Forum lists at least 18 nations in which women still need permission from their husbands to work. In many others, women are not able to decide their reproductive fates, because contraceptive treatments are denied for religious reasons or are unattainable to all but the wealthy. The World Health Organization reports that approximately 800 mothers a day die in childbirth or from pregnancy-related complications. Then there is the ongoing barbarity of physical and sexual violence against women and femicide. How can a woman be expected to “Think Different” or “Just Do It”—let alone worry about plastic pollution or the loss of wildlife—when their personal safety is threatened by a society that condones such brutality.

To safeguard the future of our planet and humanity, we must not only lift women up, but give them the opportunity to lead. From Jacinda Ardern to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, women in leadership are showing us that using empathy as our compass is the best way to achieve the kind of social reform and economic prosperity that benefits all genders, races, and classes. We must invest in reforming the institutions that ignore or do not recognize potential. We must encourage the inclusion of more women in leadership and executive positions. Positions of power. We don’t need women to work harder than they already are; we need to normalize them sitting at the global decision-making table.

Forty years later, I still have that copy of The Ocean World. I often flip through its pages and marvel at the wonder and beauty of the sea. It remains a strong symbol of so much of my personal journey. What if I had been comfortable asking my father if I could read it, or have a copy of my own? I know my father wasn’t intentionally excluding me all those decades ago, but if 2020 has taught us anything, it’s that our blind spots must be exposed. I am writing this to ask you to find your own blind spots when it comes to the girls and women in your life. Are you able to see and encourage their potential? Because what is good for women and girls is absolutely good for the Earth.

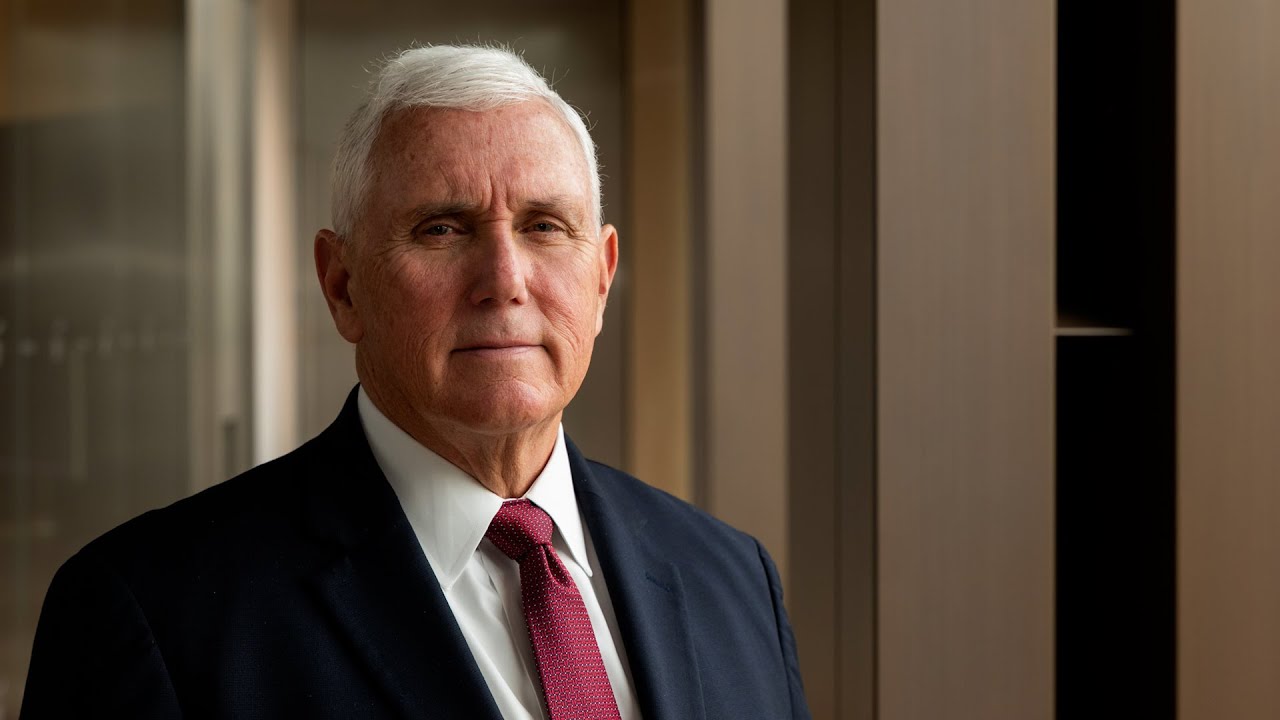

Cristina Mittermeier is co-founder of SeaLegacy. President of the Only One Collective and a National Geographic photographer.