“Many secrets, no mysteries”: That is the basic rule of all Donald Trump scandals.

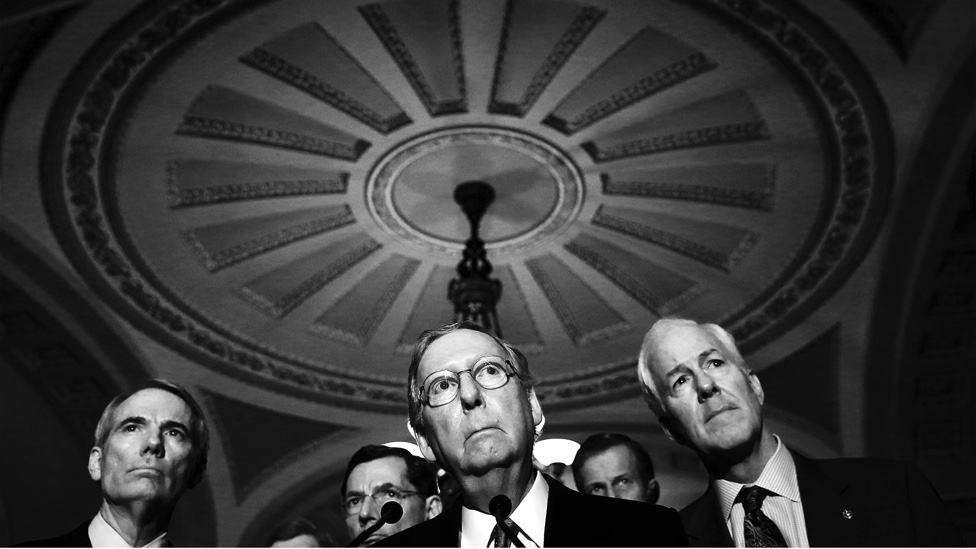

There has never been any mystery about what happened on January 6, 2021. As Senator Mitch McConnell said at Trump’s second impeachment trial, “There’s no question—none—that President Trump is practically and morally responsible for provoking the events of the day.”

Thanks to the work of the congressional committee investigating the attack on the Capitol, Americans now have ample detail to support McConnell’s assessment. They know more about when and how Trump provoked the event. They have a precise timeline of Trump’s words and actions. They can identify who helped him, and who tried to dissuade him.

But with all of this information, Americans are left with the same problem they have faced again and again through the Trump years: What to do about it? Again and again, they get the same answer: “It’s somebody else’s job.”

Special Counsel Robert Mueller investigated Trump’s collusion with Russia. Mueller brought charges against Trump’s former campaign chair, Paul Manafort; against Trump’s former national security adviser, Michael Flynn; against Trump’s personal lawyer Michael Cohen; against Trump’s longtime political ally Roger Stone; against many Russian nationals and organizations too. But on Trump himself, Mueller refused to pass judgment, because he believed he had no legal power to indict a serving president. He further believed that because he did not have that power, he should make no clear comment on whether the president’s conduct was indictable. Mueller presented evidence of Trump’s obstruction of justice, but beyond that … he tossed the responsibility over to Congress.

Within a few months of Mueller’s report, brave whistleblowers revealed Trump’s scheme to blackmail the president of Ukraine to help Trump’s 2020 reelection campaign. This time, Congress took responsibility for investigating the matter. Testimony on the record confirmed the whistleblowers’ allegations. The House impeached Trump; the Senate tried him. The main argument of Trump’s defense? Holding Trump to account should be somebody else’s job: in this case, the voters.

Trump White House Counsel Pat Cipollone argued, “For all their talk about election interference, they’re here to perpetrate the most massive interference in an election in American history—and we can’t allow that to happen.” If Trump did wrong, let an election decide the matter, not Congress. Enough Republican senators accepted that argument to ensure Trump’s acquittal.

In November 2020, the voters delivered their verdict. By a vote of 81 million to 74 million, they repudiated Trump. Trump and his supporters refused to accept the outcome. First by fraud, then by force, they tried to overturn the election. Once again, they argued, it was somebody else’s job to hold Trump to account: not the voters but the state legislatures, which should reject the popular vote and appoint their own electors instead.

Trump’s plot led to his second impeachment—and to one more round of “It’s somebody else’s job.” Trump’s attempted coup had failed, his enablers argued, and he would be leaving office on schedule. Impeachment is not the only remedy for presidential misconduct, McConnell said: “We have a criminal justice system in this country. We have civil litigation. And former presidents are not immune from being held accountable by either one.”

And so the circle was complete. Criminal prosecution? No, it’s up to Congress. Congressional impeachment? No, leave the decision to the voters. Refusal to accept an election defeat? Back to criminal prosecution.

To repeat McConnell’s phrase, it’s “practically and morally” very difficult to hold a wayward president to account. An American president is bound by law and operates through legal institutions, but a president also has sources of personal authority that are not beholden to the law and are exercised outside institutions. Trump drew more deeply than most presidents on nonlegal, noninstitutional authority.

He and his core supporters repeatedly threatened that any attempt to apply laws to him would provoke violence against the law. Trump allies and Trump himself have warned of riots if he were ever prosecuted.

Maybe these threats are empty boasts. But nothing like them has ever been heard before from a modern American leader. On January 6, Trump welcomed political violence on his behalf—and got what he wanted. He has not repented or reformed in the two years since.

But the very threat makes it all the more necessary to proceed with the January 6 Committee’s criminal referrals. If Trump does not face legal consequences for the events of that day, he and his supporters have reason to believe that Trump somehow frightened the U.S. legal system into backing down from otherwise amply justified action.

Show Trump a line, and he’ll cross it. That was his record as president, down to his last days in office, when he absconded with boxes of government materials as though they were his private property. Trump has already announced a run for president in 2024. Whatever happens with that run, his likeliest Republican rivals are studying his methods, considering which to emulate and which to discard. The incitement of violence by the head of the government is not an infraction that can be dismissed and forgiven by any political system that hopes to stay constitutional.

For six years, the job of upholding the rule of law against Donald Trump has been passed from one unwilling set of hands to the next. Now the job has returned to where it started. There is nobody else to pass it to. The recommendation has arrived. The time for justice has come.