Lisa Bodell: Change Is a Choice

In this article, Lisa Bodell challenges the way we typically think about change. Rather than viewing it as a dramatic, all-or-nothing leap, she reframes change…

Thought Leader: Lisa Bodell

Over the past few weeks a common joke I hear from family and friends is: “Hey Mike, I bet you wish you were in space now!” As today is officially “National Astronaut Day,” and I am most definitely on Earth, I will be using my astronaut experiences to deal with our current situation.

As a former NASA astronaut with two space shuttle missions and four spacewalks worth of experience, I am familiar with feeling separated from the Earth, sheltering in space with my crew mates while executing our mission with our ground control team back on the planet, coping with loss and tragedy, not letting fear get in the way of success, and being resilient to overcome unforeseen challenges while away from traditional support systems. I believe we will get through this, together.

My astronaut training and space flights have helped to prepare me for the COVID-19 pandemic we are now experiencing. When I was selected to be a part of NASA Astronaut Group 16—the class of 1996 who were nicknamed “the sardines” as we were the largest astronaut class ever selected—astronauts were preparing to be sent to space for longer periods of time and for very challenging missions.

Some of our guidelines were: embracing the situation as best we could; keeping open the lines of communication between friends, family and co-worker back on Earth; keeping a regular schedule including an emphasis on exercise, hygiene, and health; putting the well-being of our crew mates first by being respectful and practicing good “expedition behavior” while sharing our living area, and using time away from the hustle and bustle of our normal daily routines to think introspectively about our lives.

I am sure these guidelines are being used by my colleagues in space today, and can help the rest of us back here on planet Earth. My experiences as astronaut taught me valuable lessons, one of which is that our finest moments can come out of our most challenging times.

When people ask me what it feels like the first time you spacewalk, what I tell them is this: Imagine you’ve been tapped to be the starting pitcher in game seven of the

World Series. Fifty thousand screaming fans in the seats, millions of people watching around the world, and you’re in the bullpen waiting to go out. But you’ve never actually

played baseball before.

You’ve run drills and exercises with mock-ups and replicas. You’ve spent months playing MLB on your Sony PlayStation, but you’ve never once set foot on that mound.

And guess what. The Series is tied and the whole season is on the line and everyone is banking everything on you. Now go get ’em. That’s how I felt sitting in that air lock. NASA was trusting me to do millions of dollars in repairs to this billion-dollar Hubble telescope, and until that moment I’d never laid a hand on the actual telescope.

During our training, as the only two rookies, Duane “Digger” Carey and I had become close. In the months leading up to the flight in March 2002, we talked about dreaming about space since we were kids and what we were most looking forward to. Right before we launched, he’d come up to me and said, “Mass, since I’m a pilot, I’ll never get a chance to spacewalk, but you gotta do something for me. I want you to look around out there and, as soon as you get in, I’m going to come to you and I want you to tell me what it’s like. I want a description fresh from your mind. You gotta promise me you’ll do that.” Now he wanted to make sure I made good on my promise. “Good luck, Mass,” he said. “You’ll do great, and remember, I want a full report.”

I told him I would give him one, and quietly I thought to myself: I hope it’s a good one. Then John M. Grunsfeld floated over to the air lock’s inner hatch and pushed it closed. He pulled the handle down and spun it shut. It sounded like I was being locked in a prison cell. Whomp! Cha-Chunk! I looked over at James H. Newman like, “I guess this is it. There’s no going back now.”

Newman switched our suits over to their own battery power and oxygen. Then he started to depress the air lock. After a final purge of air from the air lock, we were in a

complete vacuum. There was no sound. The cha-chunk I heard when they locked us in, I wouldn’t hear that now.

At that point we were clear to go. Newman pulled open the door to the payload bay and

pushed the thermal cover aside. Then he went out first to make sure the coast was clear and to secure our safety tethers. He was out there for a few minutes.

Finally he said, “Okay, you’re clear to come out.” I put my hands on the hatch frame and pulled myself through. I was floating on my back, looking up and out of the payload bay. The first thing I saw was Newman floating above me, hanging out with this grin on his face like, “check this out!” Behind his head was Africa.

Hubble is 350 miles above Earth; astronomers wanted the telescope as far away from the planet as possible in order to have a longer orbit, see more of the sky, and be farther away from the atmospheric effects of Earth. The space station is 250 miles above Earth.

From that vantage, you can’t fit the whole planet in your field of vision. From Hubble, you can see the whole thing. You can see the curvature of the Earth. You can see this gigantic, bright blue marble set against the blackness of space, and it’s the most magnificent and incredible thing I’ve ever seen in my life.

One thing I was not prepared for was how blue it is, how much water there is. After seeing the Earth, I looked down the payload bay at the telescope, and noticed the bright light from the sun. The sunlight on Earth is filtered through the atmosphere; it can appear bright yellow or as that golden hue you get at sunset.

You get different colors depending on the place and the time of day, which in turn affects the color of objects as we perceive them. In space, sunlight is nothing like sunlight as you know it. It’s pure whiteness. It’s perfect white light. It’s the whitest white you’ve ever seen. I felt like I had Superman vision.

When you train for space walks, you’re used to moving around in the pool, where there’s drag on your suit from the resistance of the water. It slows you down and makes you more stable. In space there’s no resistance to any move you make, so you have to go really slow.

I moved up and down the forward part of the payload bay. I did some pitch and roll maneuvers, getting a sense of how it felt. I took note of how my safety tether was moving behind me so I could make sure I wouldn’t get tangled up in it.

Then it was time to go to work. The robot-arm platform was positioned right at the front of the payload bay where we’d come out. I climbed onto the top of the robot-arm

platform, slotted my boots into the foot restraints, and they clicked right into place. Flat and go. Perfect on the first try.

You see the stars, of course. You can see the whole universe. At night, without the sun, space becomes a magical place. In space, stars don’t twinkle. Because there’s no atmosphere to distort your view, they’re like perfect pinpoints of light. Stars are different colors, too, not just white. They’re blue, red, purple, green, yellow. And there are billions of them. The constellations look like constellations.

You can make out the shapes and see what early astronomers were getting at with their descriptions. The Southern Cross was my favorite. And the moon feels like it’s right there. It’s not a two-dimensional white disc anymore. It looks like a ball, a gray planet. You can see the mountains and craters clearly. It feels closer than it is.

You can see the gas clouds of the Milky Way. You’re in the greatest planetarium ever built.

Lisa Bodell: Change Is a Choice

In this article, Lisa Bodell challenges the way we typically think about change. Rather than viewing it as a dramatic, all-or-nothing leap, she reframes change…

Thought Leader: Lisa Bodell

Sara Fischer on Meta’s AI Infrastructure Push

In an article by Sara Fischer, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg outlines the company’s launch of Meta Compute, a new top-level initiative focused on scaling AI…

Thought Leader: Sara Fischer

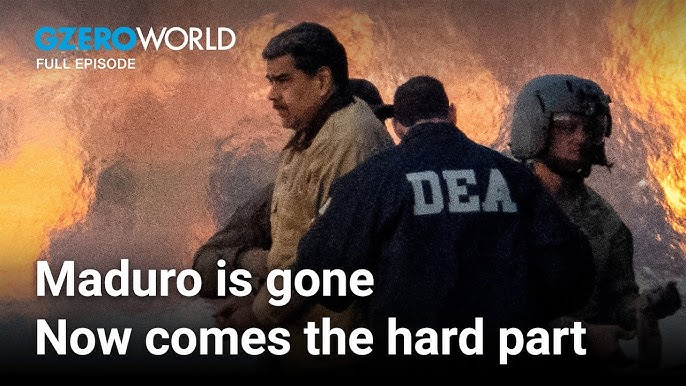

Ian Bremmer: What’s Next for Venezuela

After the US captures Nicolás Maduro, is Venezuela headed for stability, or chaos? Ian Bremmer talks to Senator Ruben Gallego and Frank Fukuyama about what…

Thought Leader: Ian Bremmer