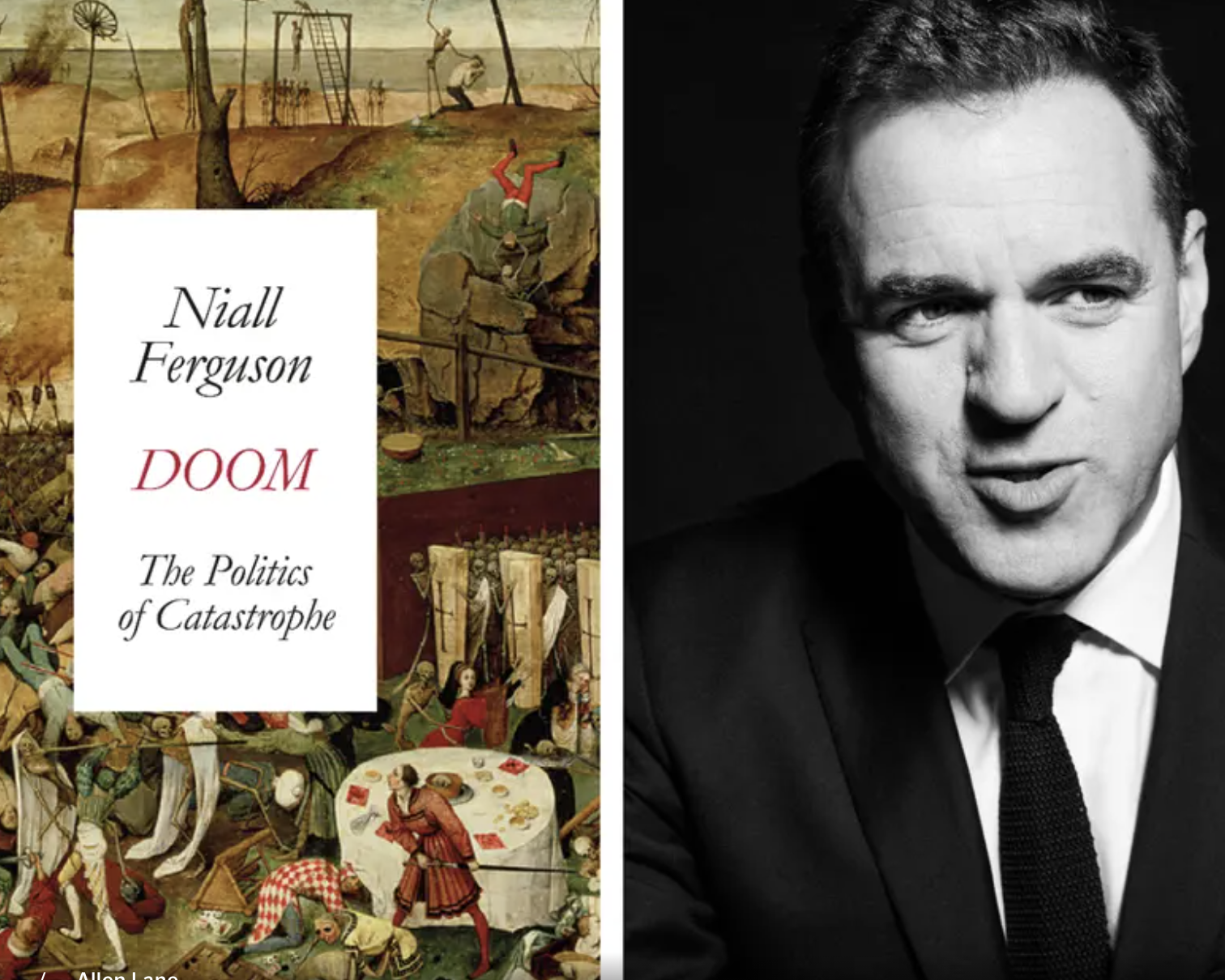

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson review

(Evening Standard) – From plagues and volcanic eruptions to the current Covid pandemic, mankind has always been faced with catastrophes.

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

The writer is the author of ‘Chip War’

The Biden administration liked to use the term “small yard, high fence” when describing its export controls on advanced chips. The idea was that highly specialised US technology had to be protected — but that the protection was limited and would not impede broader trade.

The accuracy of this was always debatable, given the centrality of these semiconductors for artificial intelligence. What is clear, however, is that China’s latest tit-for-tat expansion of export controls are part of a strategy that has no interest in limiting impact. And Europe has been caught in the crossfire.

Beijing’s major new rare earth restrictions will, at the very least, drive up prices and make non-Chinese manufacturing less competitive. This alone is a win for a country that is wrestling with sustained industrial overcapacity and sees increased exports as a driver of national power.

Even worse for trading partners is the prospect of renewed rare earth magnet shortages. Delays caused by China’s export controls earlier this year disrupted auto manufacturing from Illinois to India.

President Donald Trump has responded by threatening new tariffs. Europe, which felt less impact from the rare earth shortages this spring, is now at the centre of the supply chain struggle.

In early October, the Dutch government took control of the Netherlands-based, Chinese-owned chipmaker Nexperia, citing “governance shortcomings” and a threat to European technological capabilities. Beijing responded by halting overseas sales of Nexperia’s chips — manufactured in Europe but mostly packaged in Dongguan, China.

Nexperia’s Chinese-packaged chips are used by 49 per cent of European auto companies, 86 per cent of medical device companies, 95 per cent of the mechanical engineering sector and the continent’s entire defence industry, according to local reports. The entire western manufacturing base faces severe supply chain challenges unless China can be convinced to reopen Nexperia’s exports from Dongguan.

As the Dutch and other European governments negotiate with Beijing, some analysts are calling for a strategy of “escalate to negotiate”. This might include cutting sales of chipmaking tools and aerospace components to China.

Beijing, Brussels and Washington are all searching for the most efficient and asymmetric ways to gum up their adversaries’ supply chains.

One challenge these governments face is knowledge. It’s no secret that manufacturers struggle to understand the depths of their own supply chains. There can be dozens of transactions between a raw material and a finished good. Governments have even less visibility. China’s rare earth measures — which require multinationals to apply for licences — may be partly intended to provide Beijing with more supply chain visibility. This implies more precise targeting of any future restrictions.

A second challenge is finding measures with asymmetric costs.

Economic warfare against small countries is politically straightforward. Sanctions that impose the same cost on the US and North Korea might affect Pyongyang but be barely noticed in the huge American economy. For the world’s three largest economies, the only measures that provide real leverage are those that induce far higher costs on their rival than themselves.

The type of cost that matters most is not economic but political. China remains addicted to many overseas products, including the US dollar and Taiwanese-made semiconductors. Yet disrupting the flow of these, such as by sanctioning big Chinese banks, would hurt the west as well as China. Trump is sensitive to the stock market, which reacts negatively to any trade escalation. China’s stock market is dominated by state-directed asset managers, and President Xi Jinping has no midterm elections to worry about.

Despite the Trump administration’s aspiration to make China “addicted” to US technology, the west has been late to the game. In April 2020, amid pandemic lockdowns, Xi declared it was Beijing’s strategy to “tighten international production chains’ dependence on China”.

The Covid-19 pandemic was supposed to have forced the world’s procurement managers to shift from a “just in time” model to a “just in case” one better prepared for disruption.

But as China drip feeds rare earths to desperate manufacturers abroad, “just in time” is central to Beijing’s strategy to keep global multinationals hooked on its supply.

Professor Chris Miller is a geopolitical expert who talks about the origin, impact, and future of AI. He is the author of Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology, a book that explains how computer chips have made the modern world—and how the U.S. and China are struggling for control over this fundamental technology. Chip War won Financial Times’ Best Business Book of the Year award. Breaking down the motives behind international politics and economics in a thoughtful and concise manner, Miller provides audiences with fresh, alternative perspectives and leaves them wanting to know more. Contact WWSG to host him at your next event.

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson review

(Evening Standard) – From plagues and volcanic eruptions to the current Covid pandemic, mankind has always been faced with catastrophes.

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

One reason so many are quitting: We want control over our lives again

The pandemic, and the challenges of balancing life and work during it, have stripped us of agency. Resigning is one way of regaining a sense…

Thought Leader: Amy Cuddy

Scott Gottlieb: How well can AI chatbots mimic doctors in a treatment setting?

This is an Op-ed by WWSG exclusive thought leader, Dr. Scott Gottlieb. Many consumers and medical providers are turning to chatbots, powered by large language…

Thought Leader: Scott Gottlieb