DeMaurice Smith is the executive director of the National Football League Players Association.

If you are a high school or college football player watching the NFL Draft with dreams of being selected by an NFL team in the future, take the time to learn the story of a man named Ray Dennison, as it will reset everything you think you know about how players fit into college sports. Ray Dennison was a U.S. Army veteran, husband and father of three who came back to join the Fort Lewis A&M football team at the encouragement of the head coach. Dennison was defending the opening kickoff for the Aggies in September of 1955 when he went to make a tackle and an opponent’s knee fractured his skull. The blow to the head ultimately killed him 30 hours later.

Dennison’s widow filed for death benefits under the Workmen’s Compensation Act that were initially approved, but the school, with the backing of the precursor to the NCAA and an insurance company, successfully convinced the Colorado Supreme Court that he was neither a “student” nor a “worker” under the law. Out of that ruling, the term “student-athlete” was coined, and as a result, his widow was not entitled to any of the death benefits.

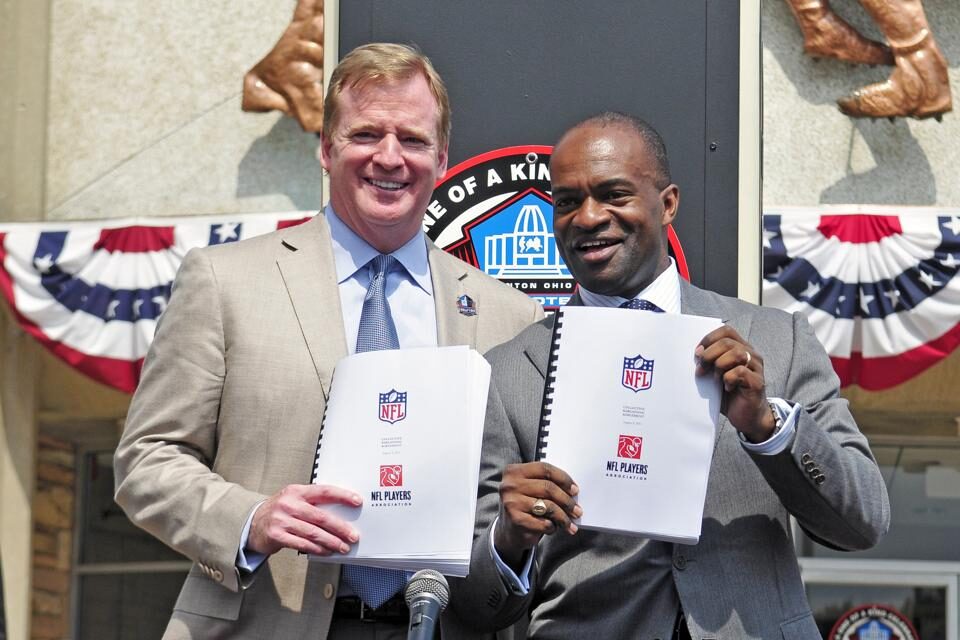

Make no mistake: The players being drafted this week are transitioning from one multibillion-dollar business into another, with a few key differences. First, they have stronger legal rights. Second, they can earn from their name, image and likeness. And third, they have a strong union to protect them. The root of those differences is the term “student-athlete,” and it is also why it is time to stop using it. Ray Dennison was the first victim of the term, and at a time when we have become rightly concerned about how we define, characterize and label people, we should be conscious of language that was designed to put a group of students into a legally and ethically disadvantaged class from the outset.

Billie Dennison and her three children view a plaque naming the stadium at Fort Lewis A&M College in 1960 in memory of Ray Dennison. (Denver Post via Getty Images)

The shameless history of this label is built on the death of an American military veteran and the subsequent efforts to protect institutions from any moral or legal liability. The NCAA has continued these efforts for decades, using the Dennison case and the term “student-athlete” to shield its powerful infrastructure from accountability while attempting to condition us to view and treat some students differently than others.

When we watch college football, we know the students are athletes. We know they have an opportunity to get a great education by receiving a scholarship. We know that many young people who played college sports go on and do great things after they graduate, both on and off the playing field. My concern is that people have avoided the real issues of graduation rates, the proper balance between school and sports, eligibility, injury care and NIL rights by deliberately engaging in the wrong starting point — all to protect the endgame of the business of college athletics.

The starting point is that the term “student-athlete” categorizes a person as being “less” and then tries to address all other issues from there. NFL players love the game just as much as players in college do, but we somehow wrap up the business of college sports in deceptively purist wrapping paper, distracting us from the real issues. Labeling college players as “student-athletes” prevents the rights of students who are athletes to engage their university on these issues as an organized team or union; stifles the conversation about a fair way to recognize the value of owning their name, image and likeness; and exposes players to all of the risk, unlike NFL players.

How is it that a student who suffers an injury during a routine on-campus job has more legal protections than a college athlete who suffers the same injury on a court or field? If you have any doubt, in 1974, Alvis Waldrep was paralyzed after a tackle while playing football at TCU, and just like Dennison, he was ultimately denied the workers’ compensation benefits that any current NFL player would receive. The college student scenario can only sound like it makes sense if we overlay the fiction that somehow a student who is an athlete “assumes” the risk — or worse, that he or she should be “grateful” to have a scholarship and/or to play a game. There is nothing that comes from the opportunity to play a college sport that should result in having fewer rights than other students at the same school of higher learning.

NFLPA executive director DeMaurice Smith speaks at a news conference ahead of Super Bowl LV on Feb. 4. (Perry Knotts / USA Today)

The NFL Draft is almost presented like a graduation ceremony, with the best college football players getting their names called to walk across the stage and hug the principal, almost entirely ignoring the fact that players are simply transitioning from one lucrative business to another.

It is telling how every year, college athletes across all sports are the ones who reveal the built-in layers of inequality, unfairness and ethical bankruptcy that have defined the NCAA’s institutional injustice for decades. It is our responsibility to support them in the pursuit of fairness and equality.

The irony is that the NCAA’s top male and female athletes are annually awarded a scholarship named after Walter Byers, who founded the NCAA and later regretted establishing the term “student-athlete” because he recognized the harm it inflicted. College players in all sports deserve better, and the memory of Ray Dennison is best served if we commit to eradicating the root of the madness so that we can have a real conversation about what is in the best interests of all students.