Patrick McGee: China’s Robots vs. America’s Chatbots

In his latest article for The Free Press, WWSG exclusive thought leader Patrick McGee argues that the global AI competition isn’t just about building the…

Thought Leader: Patrick McGee

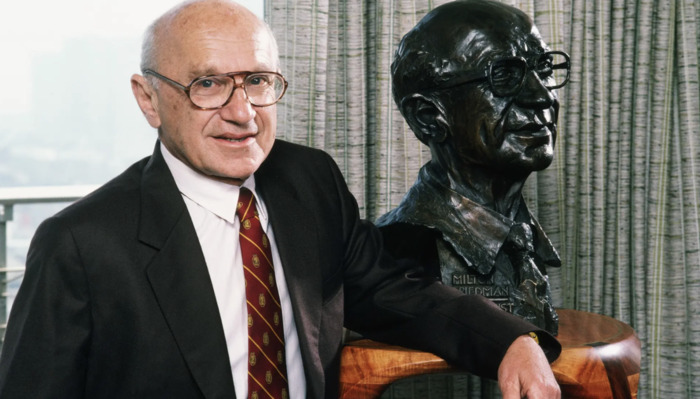

n 2020, Joe Biden declared, “Milton Friedman isn’t running the show anymore!” The intensity of Biden’s attack may obscure “a startling reality,” according to Jennifer Burns, an associate professor of history at Stanford University: Liberals as well as conservatives rely on Friedman’s analysis.

In December 1969, Time magazine put an image of University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman on its cover. The accompanying article noted that Friedman’s predictions about inflation, stagnation, and recession appeared to be coming true. Ignored and ridiculed for decades, Friedman had “an important influence on Government policy,” and was persuading economists to be “Friedmanly, Friedmanian, Friedmanic, and Friedmaniacs.”

In 1976, Milton Friedman won the Nobel Prize in Economics.

At the end of the 1970s, no less an authority than John Kenneth Galbraith declared that the age of John Maynard Keynes had given way to the age of Milton Friedman.

In the 80s, Friedman had the ear of President Ronald Reagan and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. In the 1990s, neo-liberal Democrats, including President Bill Clinton, and policymakers around the world embraced versions of Friedman’s views about free trade, privatization, and deregulation.

When Friedman died in 2006, the Guardian, a left-leaning newspaper in England, deemed him “one of the greatest economists of all time.”

In Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative, Stanford professor Jennifer Burns provides the first full-scale account of his personal and professional life, impact and legacy. Richly detailed, well-informed and informative, judicious and accessible, Burns’ book is also, in essence, a primer on economics over the last century.

Burns explains the influence of University of Chicago professors Frank Knight, Henry Simons, Jacob Viner, and Lloyd Mints on Friedman’s economic philosophy. She documents how he built his reputation by drawing on the extraordinary research and insights of four female economists: Dorothy Brady, Margaret Reid, Anna Schwartz, and his wife, Rose Director Friedman.

And Burns lays out the tenets of “monetarism,” which Friedman relied on to refute the central claim of Keynes that adjusting taxes and government spending could control inflation and unemployment, and tame business cycles. Inflation, Friedman wrote, “was always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,” not always responsive to interest rates or government spending. The failure of the United States to maintain a steady growth in the amount of money in circulation, he insisted, caused The Great Depression. The failure of Keynsians to anticipate — or provide remedies for — the “stagflation” of the 1970s, Burns emphasizes, led many economists and policymakers to acknowledge that Friedman and Schwartz’s 860-page magnum opus, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, was a game changer.

Nonetheless, Burns points out that monetary aggregates are actually “hard to measure, harder to manipulate, and an unreliable anchor amid regulatory change.” In the 1980s, moreover, Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker was able to wrestle inflation to the ground by raising interest rates.

Burns also criticizes Friedman for subordinating his concern for inequality because he thought mitigating it through progressive taxation constituted “a clear case of coercion.” His emphasis on prices and a narrow definition of cost-benefit analysis as the best measure of success, she argues, came at the expense of regulation for the common good. Diverting corporate resources to “the general social interest,” Friedman wrote in 1970, was unethical. And Burns claims that Friedman’s opinions — that requirements for schools did not include the issue of segregation and that a shop owner could refuse to hire an African American clerk if the “tastes of the community” meant he would lose customers by doing so — were “an apologia for racism.”

All that said, Burns makes a compelling case that Friedman continues to cast a long shadow on economic and social policy.

Millions of Americans watched his PBS series “Free To Choose,” read the best-selling companion volume, and endorsed Friedman’s views of the inherent inefficiency of government and the need for a political world of maximum individual choice. Friedman’s calls for the Fed to adopt rules, specify responsibilities, and practice transparency, Burns indicates, “have left a mark.” The current 2% inflation target, for example, evolved from Friedman’s monetary targets.

These days, the United States has an all-volunteer army, privatized prisons, school vouchers, and alternatives to the U.S. Postal Service. Capital flows freely across national borders. Politicians advocate tax cuts and deregulation and advocate or give lip service to balanced budgets. And the Child Tax Credit and progressives’ proposal for a universal basic income are “lineal descendants of Friedman’s negative income tax.”

Biden’s 2020 declaration that Friedman wasn’t running the show anymore betrayed “an anxiety of influence,” Burns concludes. “It implicitly acknowledges how fundamental” Milton Friedman’s analysis has become to liberals as well as conservatives.

Ironically, the principal threat to Friedman’s legacy may come from the right-wing populist nationalism of Donald Trump. But, Burns writes, “whatever social or political order emerges next, it will not be, it cannot be, a clean break from the past.” Or from the diminutive economist who has loomed large, for better and worse, for so long.

Patrick McGee: China’s Robots vs. America’s Chatbots

In his latest article for The Free Press, WWSG exclusive thought leader Patrick McGee argues that the global AI competition isn’t just about building the…

Thought Leader: Patrick McGee

John Kelly: The Impact of Veterans

10News Anchor John Becker sits down with Gen. John F. Kelly to chat about the impact of veterans and how they work to serve their…

Thought Leader: John Kelly

Erika Ayers Badan: How Great Teams Actually Work

On this episode of Unsolicited Advice, we talk about what actually makes teams work. How clarity beats charisma. Why initiative matters more than experience. Why…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan