One reason so many are quitting: We want control over our lives again

The pandemic, and the challenges of balancing life and work during it, have stripped us of agency. Resigning is one way of regaining a sense…

Thought Leader: Amy Cuddy

In 2024, there were 182 diagnosed concussions in the NFL, among the more than 1,500 players injuries diagnosed and tracked by NFL clubs each year. As would be expected, research has shown that former NFL players suffer from various medical afflictions at rates greater than the general population. And while players are generally well compensated during their careers (the minimum salary in 2025 is $840,000), careers are short (though not as short as the NFLPA claims). Consequently, it makes sense that NFL players have good benefits. Nevertheless, the benefits provided by NFL clubs – in large part as a result of demands by and negotiations with the NFLPA – are likely unmatched by any other company in America.

The NFL and its players have the most contentious history of any of the major North American professional sports leagues. In 1970, the NFLPA gained formal recognition from the National Labor Relations Board to represent NFL players. That same year, it negotiated a new collective bargaining agreement (CBA) with the NFL that for the first time required NFL clubs to provide disability benefits, life insurance, and dental benefits.

Between then and 1993, the NFLPA and NFL waged near continuous litigation concerning the terms, conditions, and benefits of players’ employment. The players went on strike three times and filed numerous lawsuits against the league, alleging that its restrictions over player pay and movement violated antitrust law. CBAs were agreed to in 1977 and 1982 which marginally improved player benefits, but which did not yet provide players the right to free agency which by then existed in MLB, the NBA, and the NHL.

The players finally gained the right to free agency in 1993 as part of the settlement of litigation and in exchange for a salary cap. The 1993 CBA focused on the core economic structure of the league, a structure that generally is still in operation today. Indeed, then-NFLPA Executive Director Eugene Upshaw described his and then-NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue’s roles as “stewards of the game to try to ensure that we have stability and growth.”

During his Executive Director tenure from 1983 to 2008, Upshaw was never regarded as the most committed advocate for player health and safety. Upshaw was a bruising offensive lineman for the notoriously physical Oakland Raiders from 1967 to 1981. His tough-nosed play help the Raiders win two Super Bowls and got him elected to the Hall of Fame. Indeed, in 2007, amid increased scrutiny over the health of former players, Upshaw reportedly said he would “break” the “damn neck” of a former player that had criticized his leadership.

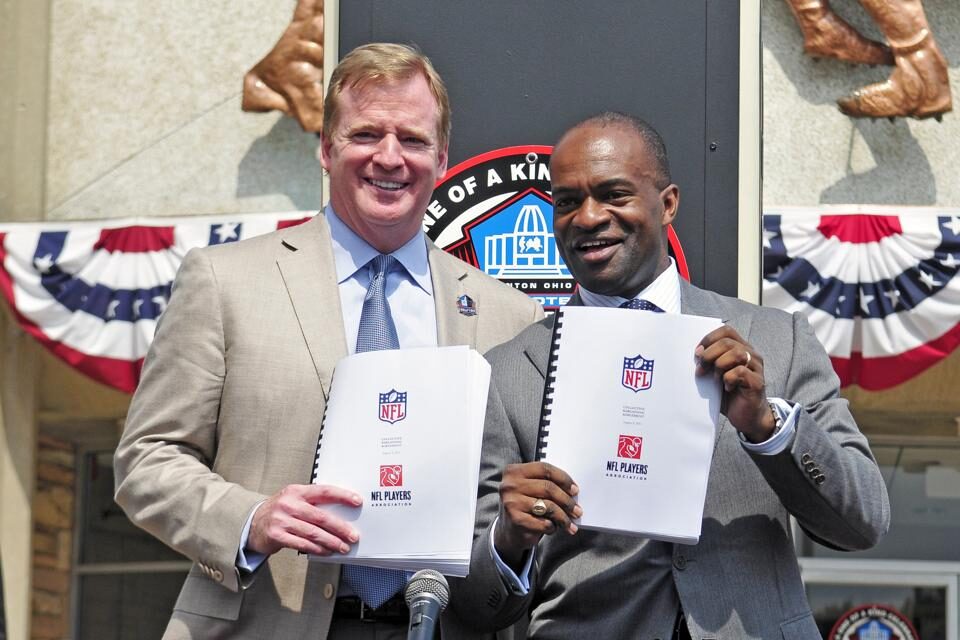

Tagliabue retired in 2006, turning over leadership to current NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell. Upshaw unexpectedly died in August 2008 and was replaced as NFLPA Executive Director the next February by litigator DeMaurice Smith. Goodell and Smith were both hauled before Congress in 2009 to answer questions about concerning reports about the health of former players and the growing scientific consensus that concussions were far more problematic than the NFL’s Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee had previously claimed.

At the same time, the players and league were fighting over player pay and benefits and the Commissioner’s right to discipline players, among other issues. With that background, in 2011, after an offseason lockout, union decertification, and commencement of yet another antitrust lawsuit, the league and players agreed to a new CBA which substantially amended and supplemented player health, safety, and benefits provisions (for a longer history of the above-described events, see Chapter 7 of this report).

The 2011 CBA was extended in 2020 and further improved player benefits. Today, NFL players are entitled to the following:

Notably, these benefits are generally non-exclusive, meaning players can take advantage of many of them at the same time if they qualify. Moreover, there are additional programs and services designed to help future, current, and former NFL players, with particular focus on transitioning to a life after football.

In 2024, each club contributed approximately $80.294 million to the players’ total benefit costs, which also includes a collective $452 million in performance-based pay. For context, the 2024 salary cap was $255.4 million per team and, according to data from Sportico, NFL clubs averaged $692.3 million in revenue last year. Consequently, about 8.6% of club revenue and 23.9% of player compensation went toward benefit costs.

There are of course many important contextual components to the above list of benefits. First and foremost, the list provides a short summary of lengthy and complex plans with far more nuance and detail than can be expressed here. Second, the process for applying and receiving benefits is a frequent subject of criticism and litigation, as many players and their attorneys have complained that it is overly bureaucratic and denies them benefits to which they are entitled. Third, the NFL is obviously a workplace with a high-rate of injury (see chapter 2 of this report), with particular concern for head injuries. Fourth, NFL careers are short – though not as short as is often presumed. The NFL and NFLPA have put forth their own data on that issue, but the only unbiased analysis known found a mean career length of 5.0 years for drafted players. And finally, the NFL is a cultural and financial juggernaut, with a reported $23 billion in revenue in 2024.

With all of that said, the NFL and NFLPA both deserve credit for providing what can fairly be described as the best benefits package of any private employer in America or close to it. The NFL’s $2 match for every $1 a player contributes to their 401(k) is exceptional, though not unprecedented (Visa, Biogen, and USAA reportedly also match 200%). Indeed, according to data from the Plan Sponsor Council of America, a non-profit trade association focused on retirement plans, only 2.7% of employers contribute more than dollar-for-dollar.

Not surprisingly then, Samantha Prince of Penn State Dickinson Law, an expert in company benefit plans, agreed that “NFL players are being taken care of much better than most employees out there.” She also pointed that there are many other jobs in which employees face high rates of injury, but that they do not have the same kind of benefits. Prince also identified the regular incremental adjustments in benefit amounts, auto-enrollment, protection against unilateral changes, and the NFL’s covering of administrative costs as valuable benefits provided in the NFL’s plans.

So while NFL players face extraordinary risks to their health, it should be at least somewhat comforting to know that they are entitled to extraordinary benefits for doing so.

One reason so many are quitting: We want control over our lives again

The pandemic, and the challenges of balancing life and work during it, have stripped us of agency. Resigning is one way of regaining a sense…

Thought Leader: Amy Cuddy

Molly Fletcher: Can drive offset your burnout at work?

This piece is by Molly Fletcher. People assume that drive depletes energy. They believe that level of intensity, focus and daily effort leads to burnout.…

Thought Leader: Molly Fletcher

Paul Nicklen: A Reverence for Nature

Standing in front of any of Canadian photographer Paul Nicklen’s large-scale images in the current exhibition at Hilton Contemporary, one cannot help but be totally…

Thought Leader: Paul Nicklen