Back in the simpler times of 2018—before the US Food and Drug Administration had to grapple with emergency authorizations in a deadly pandemic, before it scrambled to address a scandalous baby formula shortage, and before it largely bungled oversight of vaping products—the regulator dove into a sour struggle over dairy labeling.

At the time, the dairy industry was curdling as it watched the cold aisles of grocery stores fill with plant-based imposters—soy “milk” and almond “milk,” rice and coconut “milks.” In 2010, a fifth of US households were buying such non-moo juices. But by 2016, it was up to a third of households, with the defrauding dairy products slurping up $1.5 billion in annual sales. (And the trend went on; in 2020, sales hit $2.4 billion.)With the issue simmering in 2018, the FDA stepped in to extract some truths and skim the fat. In a particularly clarifying statement, then-FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb noted that the FDA, in fact, has a definition for the “standard of identity” of milk—and it appears to exclude liquids squeezed from plants.

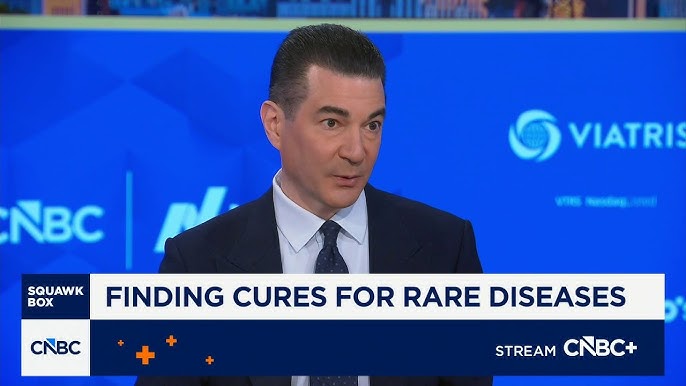

“If you look at our standard of identity, there is a reference somewhere in the standard of identity to a lactating animal,” Gottlieb said. “And, you know, an almond doesn’t lactate, I will confess.”

To be precise, the FDA appetizingly defined milk back in 1973 as “the lacteal secretion, practically free from colostrum, obtained by the complete milking of one or more healthy cows.” Colostrum, in case you were wondering, is a milky fluid produced immediately after birth before full milk production kicks in.

Gottlieb conceded at the time that he couldn’t swiftly or unilaterally wipe “milk” from almond- and soy-juice cartons nationwide. Instead, the agency would have to pore over the topic, hold focus groups, and work up new guidance. But, based on Gottlieb’s adherence to the bovine-based definition, the outcome seemed like a foregone conclusion. That is, much like blood from a stone, milk from a nut would be an unattainable secretion—or so it seemed.

In an about-face, the FDA on Wednesday released the long-awaited draft guidance with a spit-take pronouncement: Plant-based milk alternatives can keep using the term “milk.” The agency did, however, recommend—though not require—that makers of non-milked milks note on their packaging if their product has differing nutrient contents than cow’s milk.

A milk by any other name

In the guidance, the FDA acknowledged that, by its own definition of milk, plant-based milk can’t be called milk. “[T]hey are made from plant materials rather than the lacteal secretion of cows,” the FDA clarified. But, the regulator argued, essentially, that plant-based milks aren’t sold as just “milk,” they’re sold as distinct plant-based milks—and there’s no confusion about it.

“Although many plant-based milk alternatives are labeled with names that bear the term “milk” (e.g., “soy milk”), they do not purport to be nor are they represented as milk,” the FDA concluded. “The comments and information we reviewed indicate that consumers understand plant-based milk alternatives to be different products than milk. … [C]onsumers, generally, do not mistake plant-based milk alternatives for milk.”

Further, the FDA’s years’ worth of focus groups, surveys, and research revealed that many consumers purposefully buy plant-based milks “because they are not milk,” often for reasons like allergies, an intolerance, or a vegan diet.

As such, plant-based milk alternatives fall into a distinct food category from milk, which so far lacks its own “standard of identity.” In such cases, FDA regulations stipulate that plant-based milks would be considered a “non-standardized food,” which are required to bear a common or usual name that will be known to the American public.

“The names of some plant-based milk alternatives appear to be established by common usage, such as “soy milk” and “almond milk,” the FDA wrote. Thus, by law, they can and should keep their names, the agency concluded.