Time to end secret data laboratories—starting with the CDC

The American people are waking up to the fact that too many public health leaders have not always been straight with them. Despite housing treasure…

Thought Leader: Marty Makary

President Trump’s long-promised trade war could start as soon as Saturday, leaving companies scrambling for a workaround for their global supply chains.

President Trump has promised to impose 25 percent tariffs on products from Canada and Mexico starting on Saturday, a vow that’s roiling the foreign exchange market. The Times’s Peter S. Goodman, who travels the world reporting on the intersection of economics and geopolitics, breaks down where Trump’s unconventional tariff strategy has left companies scrambling to secure their supply chains.

Also, DealBook has two exclusives: Michael de la Merced reports on one of the highfliers of the online predictions market, Kalshi; and Michael Kives’s venture capital firm has reached a big settlement with FTX.

Earlier this month, I was in Colombia traveling with executives from an American medical equipment company that had set up a factory there. The company, MedSource Labs, based in Minnesota, has traditionally depended heavily on factories in China to make its goods. That no longer seemed a safe bet — not with tariffs on Chinese imports imposed by President Trump during his first term and extended during the Biden administration. Not after the chaos in international shipping during the pandemic, or disruptions to the Suez and Panama canals in recent years.

Some companies seeking alternatives to China have shifted production to Mexico, but Trump has been threatening to put tariffs on imports from that country. New duties could land as soon as Saturday.

By contrast, Colombia seemed removed from the volatility of Trump’s promised trade war. When we dropped in on a Colombian trade official in Bogotá, she was confident that her country would benefit from the Trump administration’s focus on China and Mexico, and would emerge as a more appealing place to make goods destined for the United States. “We think we are off the radar,” she said.

So much for all that.

Less than two weeks later, Mr. Trump — angered by the refusal of the Colombian government to accept American military flights loaded with deported immigrants — threatened steep tariffs on Colombia’s exports. Within hours, the Colombian government appeared to cave. The White House declared victory. The status quo held, absent new tariffs.

Still, the episode underscored how, in the Trump era, no place is truly off the radar. No country is entirely free from the prospect that tariffs may be used to gain leverage in areas outside questions of trade.

For companies that make goods for the American market, this presents a bewildering and potentially expensive problem. Major retailers like Walmart have responded to Washington’s antagonism with Beijing by shifting production to Mexico, India and other countries. About a year ago, I traveled with executives from Columbia Sportswear as they scouted factories in Central America.

How are these businesses supposed to make long-term plans while contending with the unrelenting and unpredictable prospect of tariffs almost anywhere?

Perhaps this is the intention of the Trump policy. Trump has said repeatedly that he is trying to pressure companies to make their goods in the United States. This is the most reliable way to avoid the pitfalls of tariffs.

But even American companies operating factories at home and employing American workers depend on a global supply chain to deliver parts and raw materials.

Earlier this week, I was in Louisville, a Kentucky city positioned to reap the gains of a renewed focus on domestic production. I visited with multigenerational, family-owned manufacturers that have for decades resisted the temptation to venture overseas to exploit cheaper wages.

Tariffs might protect them from lower-cost overseas competitors, but tariffs will also increase the costs of components they import — electronics from Asia, parts from Latin America, machinery from Europe. And tariffs are likely to lift the value of the dollar, which makes their goods more expensive on global markets compared to competitors from other countries.

The only certainty in all this is greater uncertainty. The Trump administration is selling a trade war as the way to bring jobs back to the United States. But it could wind up threatening jobs that are already here. — Peter S. Goodman

Time to end secret data laboratories—starting with the CDC

The American people are waking up to the fact that too many public health leaders have not always been straight with them. Despite housing treasure…

Thought Leader: Marty Makary

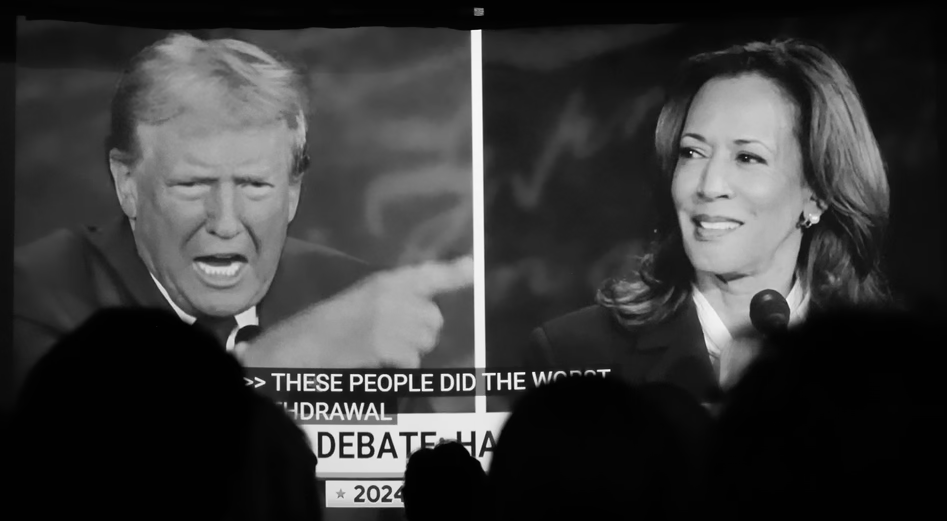

David Frum: How Harris Roped a Dope

This piece is by WWSG exclusive thought leader, David Frum. Vice President Kamala Harris walked onto the ABC News debate stage with a mission: trigger…

Thought Leader: David Frum

Michael Baker: Ukraine’s Faltering Front, Polish Sabotage Foiled, & Trump vs. Kamala

In this episode of The President’s Daily Brief with Mike Baker: We examine Russia’s ongoing push in eastern Ukraine. While Ukrainian forces continue their offensive…

Thought Leader: Mike Baker