Time to end secret data laboratories—starting with the CDC

The American people are waking up to the fact that too many public health leaders have not always been straight with them. Despite housing treasure…

Thought Leader: Marty Makary

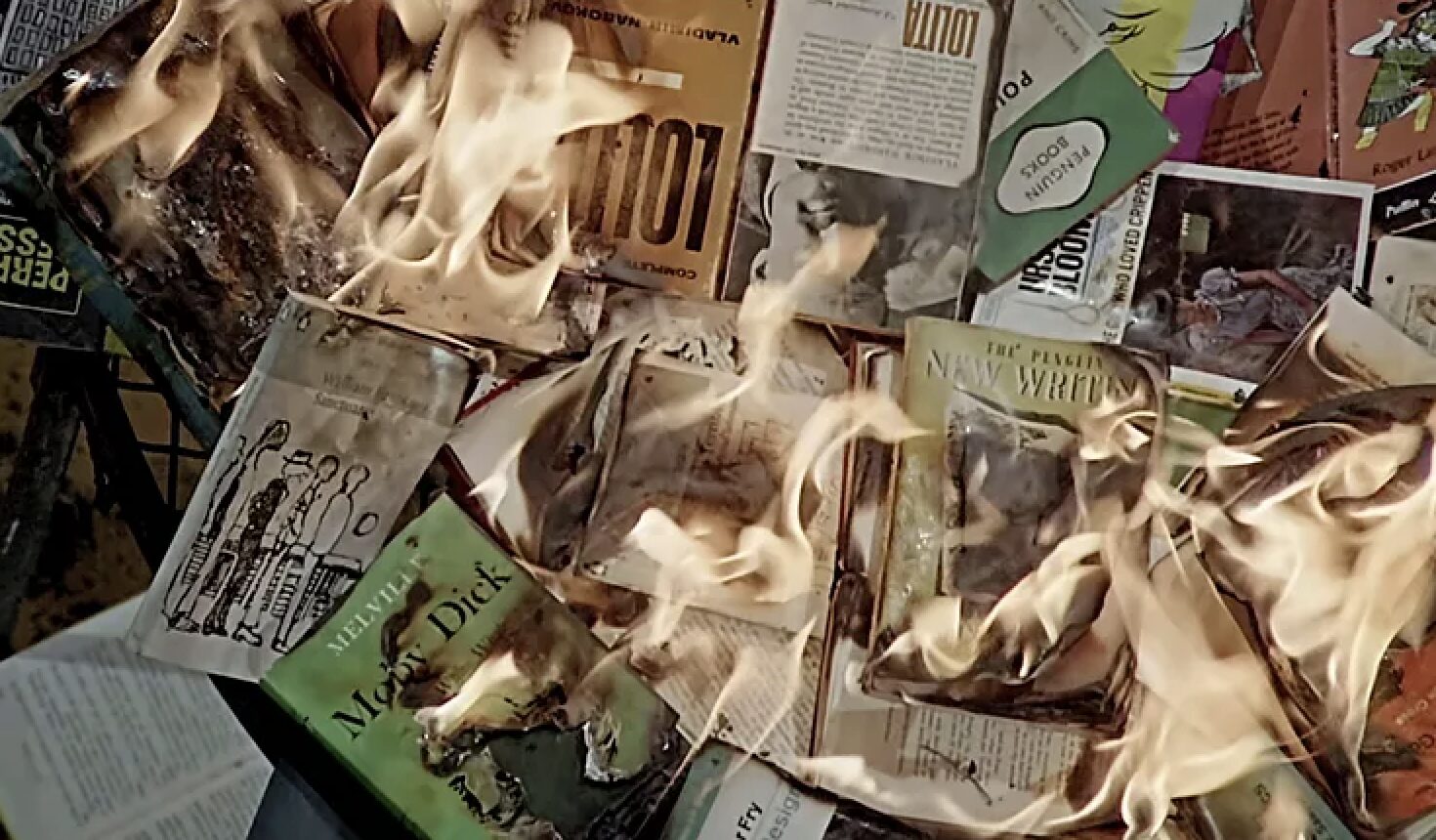

He wanted above all . . . to shove a marshmallow on a stick in the furnace, while the flapping pigeon-winged books died on the porch and lawn of the house. While the books went up in sparkling whirls and blew away on a wind turned dark with burning.” —Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451

It’s hard not to be impressed by Ray Bradbury’s prescience.

In his best-known novel, the dystopian classic Fahrenheit 451 (1953), he combined the memory of Nazi book burnings with the experience of Joseph McCarthy’s “Red Scare” to imagine a future America where firemen are employed not to put out fires, but to start them in any home where illicit book reading is detected.

Bradbury naturally assumed that any society where books were generally prohibited would be a totalitarian one. The unnamed city he imagines is in many respects an American version of George Orwell’s London in 1984. What makes it distinctively American is that the authoritarian regime is combined with a hedonistic consumer society very different from the austerity of Orwell’s dystopia.

Guy Montag, the fireman central character of Fahrenheit 451, is married to mindless Millie, who flees serious thought or conversation with the assistance of sleeping pills, giant flat-screen televisions, and what we would now call earbuds. Bradbury writes: “In her ears the little Seashells, the thimble radios tamped tight, and an electronic ocean of sound, of music and talk and music and talk coming in, coming in on the shore of her unsleeping mind.”

Millie and Guy live under a government that is actively trying to deprive its people of the power to think by eradicating books, the vessels of knowledge.

What Bradbury failed to anticipate is that his native America—and indeed the Western world—might turn away from literacy voluntarily, without the need for political tyranny.

The consumer society has turned out to be enough to make us turn away from books. And turn away fast.

The evidence has been accumulating for some time that Americans are no longer choosing to read. Here’s just a handful of the data:

But the real concern is the decline of reading among young people. According to a 2022 survey, baby boomers read more than double the number of books per year than millennials and Gen Zers. And according to a 2025 study, only 14 percent of 13-year-olds reported reading for fun almost every day in 2023—a dramatic fall from 30 percent in 2004 and 37 percent in 1992

I would be surprised if anyone engaged in the archaic activity of reading this essay were surprised by this data. Because the evidence is all around us.

On the train, the bus, or the subway, we see our fellow passengers hunched over their smartphones. In the past, at least some of them would have been clutching books. At home, we fight incessantly with our children over “screen time,” not least because we know it is taking the place of book time. We people of the book hail Jonathan Haidt’s bestseller, The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. Our cure-all remedy for Generation Z’s multitude of mental ailments is to lock them all up in the New York Public Library for a month.

It’s true, of course, that we are witnessing the rise of the audiobook. (In the U.S., according to Publishers Weekly, revenue from audiobook sales grew by 22 percent in 2022.) You can quibble about the relative merits of reading to oneself or having another person read a book aloud to you, but it seems clear that audiobooks are allowing us to consume books in ways that previously were impossible—while driving, jogging, biking, even cooking and doing the dishes.

But audiobooks won’t help with the fact that there’s a decline of literacy—the ability to read and write. When people stop reading, they stop being able to read. And I mean that, well, literally: Average adult skills scores for literacy compared with 2014 are down 12.4 points. Andreas Schleicher, director for education and skills at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, said last year that 30 percent of American adults “read at a level that you would expect from a 10-year-old child.”

And when people stop being able to read—to make sense of the meaning of text on a page—they also lose the ability to make sense of the world.

At stake here is nothing less than the fate of humanity, given the intimate connection between the written word and civilization itself. In the beginning was the word. And in the end.

At first, the written word seemed to do remarkably well in the internet age. The World Wide Web was essentially a distributed network for web pages largely composed of text, with a modest amount of illustrative art, linked together by text URLs. Blogging was writing. That continued to be the case throughout the rise of the network platforms. All Amazon ads rely on textual information. Google searches for text. Most Facebook posts were written. The same goes for most X posts, even if the length of a post was artificially constrained to encourage brevity.

Three things are now rapidly eroding the dominance of text. First, encouraged by the peculiar difficulty of the iPhone keyboard, there’s the rise of the emoji, which is in reality a return to the pictograph, a primitive pre-alphabetic form of written communication.

Then comes the ascendancy of audio and video, epitomized by the proliferation of podcasts and the rise of TikTok. The important change here is the death of the script. Until recently, nearly all entertainment on radio and television, and in the cinema, started out as written words. Only in the past decade has improvised chatter driven out carefully crafted lines of dialogue.

Finally, though artificial intelligence remains largely text-based—because most prompts still have to be typed out—that is starting to change. Since the advent of reliable dictation software, inputs are increasingly spoken. For years now, it’s not been necessary to type an inquiry into Google; we can just ask Siri. Which brings us to the next phase: Outputs, too, are increasingly non-textual. Think of the current effort by OpenAI to promote Sora 2—which generates videos from text prompts—and is clearly seen as a potential money-spinner.

In short, we are moving rapidly toward a future where information will be shared via spoken words and images, not text, with computer code as the language spoken by computers to one another, intelligible only to a minority of humans.

Why did people find it necessary to go beyond cave paintings and pictographs?

The answer is that a society of any commercial complexity cannot function on the basis of emojis.

Five millennia ago, cuneiform writing was first used in southern Mesopotamia as a means of keeping accounts—counting, cataloging, trading in agricultural produce. Property rights also required written records: The first private legal documents for the sale of land appeared in Mesopotamia. The first codes of law appeared in Mesopotamia around 2100 BCE, exemplified in the Code of Hammurabi (c. 1750 BCE), which was inscribed on stone stelae throughout the Old Babylonian Empire.

In other words, without text it is hard to keep track of and communicate the rules that are necessary in a society of any complexity.

Literature came later and served a state-building purpose. The Epic of Gilgamesh is an early second-millennium BCE work of epic poetry that glorified a Sumerian king. Scribes ran ancient Egypt for the pharaohs by strictly upholding written traditions—hence the old joke that Egypt was “nation of fellahin [peasants] ruled with a rod of iron by a Society of Antiquaries.”

Again, without text, it is hard to keep track of the stories that convey a civilization’s foundational myths to each successive generation.

Writing was also crucial in the history of monotheism. The Torah, comprising the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, codified the laws of ancient Israel. Not by chance, the Gospel of St. John begins: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” The spread of Islam in the seventh century CE brought about the rapid establishment of Arabic as a major literary language in much of the Mediterranean and Central Asia.

Without text, it is hard to keep track of the stories that help us understand our purpose in this world and our relationship to the divine.

Of course, for the first three and a half millennia that written language existed, all these stories could be tightly controlled by elites. That did not change until two transformative events in Europe: the advent and rapid proliferation of the printing press, beginning in the 1440s, and the Protestant Reformation, with its insistence that congregations as well as priests should be able to read scripture.

In 1383 it had cost the equivalent of 208 days’ wages to pay a scribe to write a single missal (service book) for the bishop of Westminster. Printing drastically cut the costs. By the 1640s, thanks to the presses, over 300,000 popular almanacs were sold annually in England, each roughly 45 to 50 pages long and costing just two pence, at a time when the daily wage for unskilled labor was 11 1/2 pence.

Cheap books and pamphlets were what enabled so many people to learn to read. Protestantism provided the motive to teach them to do so. This was what led to the spread of literacy. And it changed the world as profoundly as the later Industrial Revolution, which would have been impossible without workers who could read.

As literacy grew more widespread, so political participation could also become broader. In France the proportion of men able to sign their own name rose from 29 percent in the 1680s to 47 percent in the 1780s. In Paris on the eve of the French Revolution, male literacy was around 90 percent. Later, the abilities to read and write were spread beyond Europe by colonization, commerce and, especially, by Protestant missionaries.

Literacy was not intended to enable people to think for themselves. But that was its effect. And that’s not all it did.

In a brilliant 1963 essay, “The Consequences of Literacy,” the anthropologist Jack Goody and literary critic Ian Watt argued that the invention of writing, most decisively in ancient Athens, was a fundamental turning point. It was “only then that the sense of the human past as an objective reality was formally developed, a process in which the distinction between ‘myth’ and ‘history’ took on decisive importance.”

There emerged for the first time “the notion that the cultural inheritance as a whole is composed of two very different kinds of material; fiction, error, and superstition on the one hand; and on the other, elements of truth which can provide the basis for some more reliable and coherent explanation of the gods, the human past, and the physical world.”

When you read this, you see that our growing susceptibility to fake news and conspiracy theories are less a consequence of changes in mass media, and more a reflection of a fundamental civilizational crisis of literacy.

Compare a literate society with a nonliterate one. Goody and Watt contrasted the literate cast of mind—one capable not only of historical but also of philosophical and scientific reasoning—with its nonliterate opposite, characterized by “structural amnesia” and a blurring of the line between past and present, individual and society. In preliterate societies, they argued, “the cultural tradition is transmitted almost entirely by face-to-face communication; and changes in its content are accompanied by the homeostatic process of forgetting or transforming those parts of the tradition that cease to be either necessary or relevant.

“Literate societies, on the other hand, cannot discard, absorb, or transmute the past in the same way. Instead,” they observed, “their members are faced with permanently recorded versions of the past and its beliefs. . . . This in turn encourages skepticism; and skepticism, not only about the legendary past, but about received ideas about the universe as a whole.”

It seems likely that the postliterate society will look much like the preliterate one.

If we gradually cease to base our social and political organization on the written word, it follows that there will be three consequences.

First, we shall quickly be cut off from the heritage of all the great civilizations, as books are the principal repository of past thought. Books are the principal way a civilized person learns about the distinction between noble and ignoble conduct, for example. This means that the next generation will have a significantly larger proportion of outright barbarians than any in the past century. For people are not innately civilized. The fewer books they have read, the more easily they can be persuaded that—for example—Adolf Hitler was the hero of World War II and Winston Churchill the villain.

Second, we shall revert to the preliterary conflation of present and past, history and myth, individual and collective. The essence of the conspiracy theory is that it preys on the illiterate mind.

Third, we shall quickly lose the ability to think analytically, because the crucial way our civilization has been transmitted from generation to generation is through the great writers, from whom we learn how to structure an argument so that it is clearly intelligible to others. You may think you are learning from the podcasts you listen to. But I defy you to write down the arguments you heard a week ago, much less the evidence that was adduced in support of them.

Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 offered a vision of a bookless, authoritarian future. But the more I think about where we’re going, the more I realize that the loss of literacy will amount to going back in time rather than forward.

For a few of us old bibliophiles, there may be a chance to preserve our status as scribes, and to pass on our reading and writing habits to our children, in homes and cloister-schools where screen time is strictly rationed.

But for the growing number who are opting out of literacy, it is not the road to serfdom that awaits—but the steep downward slope to the status of a peasant in ancient Egypt.

WWSG exclusive thought leader Sir Niall Ferguson is one of the world’s foremost historians of economics, international relations, and global power. His incisive analysis illuminates the geopolitical forces and economic undercurrents shaping the 21st century. From great power competition to emerging security challenges, Ferguson offers unparalleled historical context and strategic insight — helping global leaders, policymakers, and business executives anticipate what lies ahead. To invite Sir Niall Ferguson to your next event, contact WWSG.

Time to end secret data laboratories—starting with the CDC

The American people are waking up to the fact that too many public health leaders have not always been straight with them. Despite housing treasure…

Thought Leader: Marty Makary

Scott Gottlieb: How well can AI chatbots mimic doctors in a treatment setting?

This is an Op-ed by WWSG exclusive thought leader, Dr. Scott Gottlieb. Many consumers and medical providers are turning to chatbots, powered by large language…

Thought Leader: Scott Gottlieb

Sara Fischer: The AI-generated disinformation dystopia that wasn’t

This piece is by WWSG exclusive thought leader, Sara Fischer. Amid the craziest news cycle in recent memory, AI-generated deepfakes have yet to become the huge truth…

Thought Leader: Sara Fischer