Dr. Sanjay Gupta: A New Way to Heal

Doctors have long prescribed pills and procedures. But for some people, that isn’t enough. Sanjay sits down with Julia Hotz, author of The Connection Cure, to explore the…

Thought Leader: Sanjay Gupta

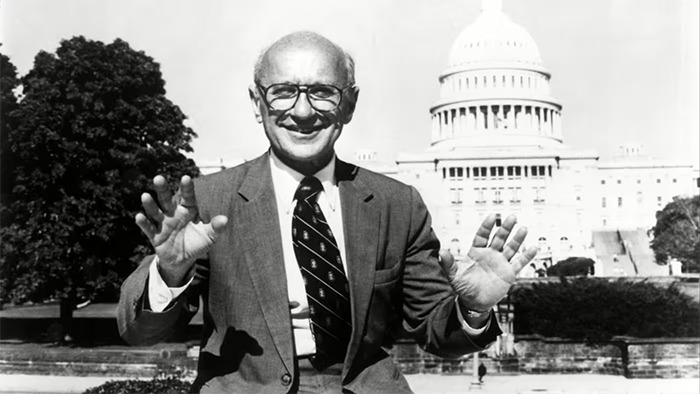

At the very moment Milton Friedman was due to receive his 1976 Nobel medal from the king of Sweden, a protester — well disguised in white tie and tails — jumped from his seat. Amid gasps from the audience, the young man shouted, “Down with capitalism, freedom for Chile!” The previous year, Friedman had met with Augusto Pinochet to discuss economic policy. With Pinochet’s 1973 coup still painfully fresh, many on the left denounced Friedman as an apologist for the junta and evangelist for unbridled capitalism.

Ushers quickly removed the demonstrator and the ceremony resumed. But with thousands marching outside, it was clear that the diminutive professor, standing just over five feet tall, was now a colossus, the most famous — or infamous — economist in the world.

As a political economist and policy adviser, Friedman resides among the great social thinkers of the postwar era. In the pantheon of 20th-century economists, only John Maynard Keynes surpasses him. As a free-market ideologue, Friedman, who died in 2006 aged 94, occupies a more contentious spot, somewhere between prophet and crank depending on one’s disposition.

But that he was singularly influential is unquestionable: Friedman, Jennifer Burns writes in her splendid new biography, “was a prime mover in the central economic transitions of the century”. He witnessed the destruction of the laissez-faire order during the Great Depression, became an economist during the construction of the New Deal order, and then contributed to its replacement by the neoliberal order.

While studying at the University of Chicago in the 1930s, Friedman absorbed the free-market philosophy espoused by Frank Knight and other like-minded faculty. His thinking on government and markets was somewhat fluid over the ensuing decade — he voted for Roosevelt and even worked in Washington during his presidency — but soon enough Friedman became the pre-eminent exponent of the neoliberal Chicago school. Indeed, he was so fundamental in shaping economic thought, argues Burns in Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative, that we cannot understand today’s economic system without understanding him.

Doing so is not easy, for his impact is such that it can be hard to remember the pre-Friedman era. As Burns notes, “Many aspects of our contemporary world that today seem commonplace have their origins in one of Friedman’s seemingly crazy ideas.”

To take one example: after the second world war, economic orthodoxy called for fixed exchange rates, as expressed in the Bretton Woods agreements. But in 1953, Friedman brilliantly argued that exchange rates should be market-determined just like any other price. Though few took the idea seriously at first, 20 years later Bretton Woods collapsed, major currencies began to float, and the benefits of flexibility became widely accepted.

Bucking convention was a habit of Friedman’s. With the Keynesian revolution, economists embraced government intervention through spending and taxes (fiscal policy) to stabilise the economy while dismissing central bank action on interest rates and money supply (monetary policy) as ineffective. Friedman challenged this view, arguing not only that monetary policy matters, but that the quantity of money is key for determining output and prices, and that central banks should target money supply growth.

Even more striking, he did so by immersing himself in history, a field usually neglected by economists, writing the seminal A Monetary History of the United States with Anna Schwartz. While Friedman’s fixation on money supply has not aged well — the relationship between money supply and inflation is not as firm as he thought, and central banks now adjust interest rates rather than target the money supply — there is no doubt that his research helped restore monetary policy to relevance.

Beyond academic debates, Friedman was a crusader for freedom, or at least his notion of freedom. Given overregulation in the decades after the second world war — not to mention the stifling controls of the communist bloc — his advocacy for free markets certainly had merits.

But in going from the seminar room to the public sphere, his thinking too often became absolute, shorn of nuance. Such was his antipathy to government intervention that he opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Self-confident in the extreme, he could not always see the other side; his response to those protesting his Nobel acceptance was to compare them to Nazis. Friedman may have been an advocate for freedom, but as Burns concludes, “his concept of freedom was woefully thin.”

If at times the book jumps around, that is in part because Friedman led a frenetic life, quarrelling in faculty meetings at one moment, advising heads of state the next, then firing off memos to central bankers before drafting his Newsweek column (with the assistance of his wife Rose). Burns tells the story of this dynamo with crisp prose supported by prodigious research. She covers the pivotal moments in Friedman’s personal life, but her focus is squarely on his career and research. The result is thus more than a biography: it is an insightful history of economic policy and thought.

Nevertheless, Friedman the man remains something of a mystery. All the pieces of the puzzle are there, yet it is not quite clear how they fit together. How did Friedman, both scholarly analyst and ardent ideologue, understand himself? Were there moments of introspection? Did he feel tension between his two halves?

Given his self-assurance, one suspects not. However, were he alive today, perhaps he would question what has become of the conservative movement he did so much to energise. Burns worries that Friedman is the “last conservative” of his kind, as support for free markets and trade has given way to rank populism and conspiracy peddling. A champion of competition, Friedman would surely have enjoyed the chance to make his case one more time.

Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative by Jennifer Burns Farrar, Straus and Giroux $35, 592 pages

Dr. Sanjay Gupta: A New Way to Heal

Doctors have long prescribed pills and procedures. But for some people, that isn’t enough. Sanjay sits down with Julia Hotz, author of The Connection Cure, to explore the…

Thought Leader: Sanjay Gupta

Niall Ferguson: Trump’s World Order Live From Davos

Live from Davos, Scott Galloway and historian Niall Ferguson examine why today’s geopolitical moment looks less like a “new world order” and more like a…

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

Mike Pence Talks Trump’s Foreign Policy

Former US VP Mike Pence discusses President Trump’s foreign policy with Greenland, Russia, and Ukraine. He says he commends President Trump on finding a framework…

Thought Leader: Mike Pence