Fifty years ago, pianist Keith Jarrett created one of the most iconic records of the era and the best-selling solo piano album ever. But “The Köln Concert” almost didn’t happen.

On Jan. 24, 1975, Mr. Jarrett arrived in Cologne, West Germany, drained and hungry after a long car trip from Switzerland. He hadn’t slept in two days. His concert at the Opera House, organized by 17-year-old Vera Brandes, wasn’t scheduled to begin until 11 p.m. The promised Bösendorfer Imperial concert grand piano was missing. In its place stood a battered, out-of-tune rehearsal piano; only its middle register worked adequately. Seeing the recording equipment already set up and the 1,400-seat house sold out, Mr. Jarrett reluctantly agreed to perform. But, he said, “I was nodding and spacing out.”

What followed was a triumph over adversity, an improvisational marvel that built on years of musical mastery. Born in Allentown, Pa., in 1945, Mr. Jarrett was a child prodigy, performing publicly by age 5. After studying at the Berklee School of Music in Boston, he moved to New York and played with jazz legends Art Blakey, Charles Lloyd and Miles Davis. In 1971, he began recording for the fledgling German label ECM, founded by Manfred Eicher, who would offer the virtuoso the freedom to record jazz trios and quartets, immortalize his solo concerts and compositions, and reinterpret works by Bach and Mozart.

That chilly night in Cologne, Mr. Jarrett played solo for an hour, with just two interruptions for applause. Not a sheet of music was in sight.

The pathbreaking artist has described his solo concerts as requiring him to be three people: an improviser, a spontaneous composer, and a listener at the keyboard. Asked how he achieves this, he wrote in 2003: “I don’t know. I just do it. When it works, it is inexplicable.” It’s one thing to improvise a melody atop the chords of a standard like “’Round Midnight.” It’s quite another to approach the piano with no preconceived themes or structures, a completely blank slate, and launch into pure invention. That’s what Mr. Jarrett says he did. The fourth and final part, however, was an encore, though not labeled as such, that became known as his lyrical “Memories of Tomorrow.”

In the Cologne concert, a small miracle of spontaneity and creativity, Mr. Jarrett dives deeply into his inner flow of feelings and thoughts. His musical stream-of-consciousness seems to rush around rocks, find calm eddies, dance in the moonlight, and surge over falls. Gospel and blues inflections, Debussy-like harmonies, harp effects, rhythmic contrasts and subtly shifting repetition all weave through the performance. His exquisite touch enhances moods that range from reflective and hypnotic to urgent and passionate.

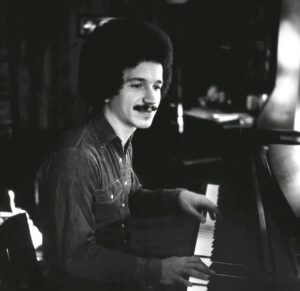

No video exists of the Cologne concert, but Mr. Jarrett’s typical intensity during performances is well-documented. He would kneel, crouch, hunch and stand at the grand, eyes tightly closed, emitting sighs, cries and grunts, even stomping on the pedals. One moment, he would coax delicate beauty from the keys; the next, he’d command the instrument like a force of nature. His performances were ecstatic, whole-body-and-mind workouts.

Consulting Mr. Jarrett, Mr. Eicher and engineer Martin Wieland spent several days in the studio to clean up the tape, compensate for the piano’s deficiencies, and add ethereal reverberation to enhance the acoustics of the hall. Because an LP could hold only about 25 minutes of music per side, the performance was divided into four parts to fit on two vinyl discs.

The album was hailed by critics and embraced by the public, to date selling about four million copies—nearly unprecedented for a jazz-related record. It opened an inviting door to instrumental jazz for countless young listeners, expanding the music’s audience. Against Mr. Jarrett’s desires, however, some conflated his album with New Age music, a genre jazz purists disdained as lightweight.

So revered is the recording that the eminent German publishing house Schott, known for Mozart, Beethoven and Stravinsky, issued an exact transcription. Classical pianists now perform this spontaneous invention, ironically, note-for-note. Which raises the question: Is the Cologne album jazz or classical? It’s not one or the other; it’s both. Or better yet, to borrow Duke Ellington’s phrase, it’s “beyond category.”

In 1998, Mr. Jarrett announced he was battling chronic fatigue syndrome, yet he soldiered on until 2018, when two strokes partially paralyzed his left side and hand and ended his illustrious performing career. But before his personal calamity, his dozens of recordings, including “The Köln Concert,” cemented his place in the musical pantheon.