Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

Scott Harrison was 28 years old and partying in Uruguay when he had a fundamental, existential break.

“I had gone on a trip to Punta Del Este and realized on that trip, I had gotten most of the things I thought would make me happy and they hadn’t,” Harrison tells CNBC Make It. “Even though I drove a B.M.W. and had a nice apartment in New York City, my life was a mess.”

In the midst of throwing house parties with hundreds of guests, Harrison made a promise to himself: He “vowed to come back and change my life,” he says.

And change his life he did, as well as the lives of millions of others.

Harrison founded the non-profit organization Charity: water, which since 2006, has given 8 million people around the world access to clean water by funding nearly 30,000 water projects in 26 countries across the world. Over one million people have donated more than $300 million to its cause.

Charity: water is driven by the stories of the individuals it helps and those who donate.

For example, Thursday is the 25th annual World Water Day, which serves to call attention to the fact that 2.1 billion people live without safe drinking water at home, according to the event’s website. To recognize the day, Charity: water is highlighting one donation as a call to action: Six-year-old Nora Jackson from Virginia sent the non-profit $8.15 in collected dollar bills and coins after watching a Charity: water video with her dad. The donation included a handwritten note, “I do not want people to die because of water.”

But before Harrison could help others change the world, he had to transform himself.

Going to extremes

Harrison was born in Philadelphia and grew up in Hunterdon County, New Jersey, an only child in a “very conservative family.” His father was an executive at a small company that sold electrical transformers.

His mother, meanwhile, was very ill. When Harrison was 4, she fell victim to a carbon dioxide leak and, though she survived, it made her ultra sensitive to chemicals.

She “lived in a tile bathroom in our house that had been scrubbed down with a special soap 20 times and on a cot that had been washed in baking soda 20 times. There was tin foil covering the doors,” he recalls. She had to wear a charcoal mask on her face “a barrier against toxins, it was it was monitoring the air, filtering the air that she breathed,” says Harrison.

“I was in really a caregiver role helping to do the cooking, the cleaning,” explains Harrison.

When he graduated from high school, Harrison high-tailed it to New York City, eager to live on his own — “Okay, now it’s my turn!” he recalls thinking. He attended New York University from 1994 through 1998, but was, by his own admission, a terrible student. He majored in communications as a path of least resistance.

Harrison was the keyboard player and band manager for Sunday River from 1992 to 1994, and played at then-famous music clubs around New York City like CBGBs, The Lion’s Den and The Wetlands. Though the band was short lived because the musicians couldn’t get along, it introduced Harrison to the world of club promoters.

From ages 18 to 28 Harrison lived what he calls his “decade of clubs,” working as a promoter for some 40 venues. “We bring the beautiful people, we bring the clients who can spend a thousand dollars on a bottle of champagne, or $500 in a bottle of vodka. We were kind of mercenaries — we would get a percentage of all the sales that happened that night but with no loyalty to the venue, so the minute the venue cooled down, we would take our set to the hottest club,” explains Harrison.

On a good night, Harrison grossed anywhere from $3,000 to $5,000. He was also an influencer before there was social media — both Bacardi and Budweiser paid him and a friend $4,000 a month to drink their brands in public.

Harrison was working all night and sleeping all day. He “was out drunk almost every night,” he recounted in a video posted by Charity: water.

“I had just had become a really selfish sycophant. Hedonist. I had betrayed the spirituality and the morality of my childhood, smoked two packs of cigarettes [a day] for 10 years. I had a gambling problem. I had a pornography problem. I had a drinking problem,” Harrison tells CNBC Make It.

He knew he was lost and started reading about theology. “I was trying to find a way back. I’d grown up with a Christian faith that I’d completely walked away from,” he says.

And it was in Punta Del Este that Harrison made up his mind to change his trajectory. “It was a soul-searching couple of weeks for me, amidst the party that was happening,” he says.

A total 180: From night life to serving others

In 2004, Harrison returned to New York City and started applying to humanitarian groups including Oxfam, the Peace Corps and the United Nations. “I’m denied basically by all the organizations because no one knows how a nightclub promoter would be useful to their important, serious adult work,” says Harrison.

Eventually, though, he was accepted by Mercy Ships, a non-profit organization of floating hospitals that brings medical help to those in need. To volunteer, Harrison paid $500 a month. For his first trip in October 2004, he lived on a converted cruise liner off of the coast of Liberia and took pictures of the work the non-profit was doing.

The poverty and pain he witnessed were profound. He took 50,000 photos of patients with conditions like leprosy, tumors and cleft lips. He also took photos after they had been treated. He emailed the shots to the same email distribution list of 15,000 he had collected while working as a promoter in New York. People started donating to Mercy Ships and to support Harrison’s work as a result.

“I realized that, wow, I could inspire positive action, compassion, empathy among people who, frankly, I didn’t even think had it in them,” says Harrison.

Back in New York City he put on a gallery show in Chelsea with 109 of the photos he’d taken in Africa. The exhibition raised $96,000. Harrison gave all of the money to Mercy Ships and then went back for a second tour.

It was on that trip Harrison learned about the importance of having clean water and many people’s lack of access. Approximately three in 10 people around the world don’t have safe, readily available water at home, according to a July 2017 report from the World Health Organization and UNICEF. What’s more, 844 million people not have access to any basic drinking water service at all, according to the joint report. There are 263 million who have to spend more than 30 minutes per trip collecting water away from home, and 159 million who drink untreated water from streams and lakes.

This and a lack of access to sanitation result in the death of 361,000 children under the age of 5 each year, according to the WHO and UNICEF. The deadly combination also results in the transmission of cholera, dysentery, hepatitis A, and typhoid.

Harrison was struck by the pain and suffering, but also by his ability to make a difference. “I felt like I was helping by telling the story,” says Harrison.

The change in his life was uncanny. He’d gone from selling rich Manhattan club kids $10 bottles of water (which they often didn’t even open) to witnessing people die from a lack of clean drinking water in third world countries.

The launch of Charity: water

In June 2006, Scott returned to New York City. He had found an issue he was deeply committed to, but he had no money. He was sleeping on a closet floor in the New York City loft of a friend from his club days.

“I was running around telling everybody I wanted to see a world where everybody drank clean water regardless of where they are born,” says Harrison.

Officially, Charity: water launched on September 7, 2006 — Harrison’s 31st birthday. Two days later, he threw a party at a nightclub in Manhattan’s trendy Meatpacking District and had everyone donate $20 cash at the door. He got the location and booze donated via his network from his old club-promoter days. He raised $15,000 and donated 100 percent of the money to a refuge camp in Northern Uganda, funding the repair of three broken wells and the construction of three new wells.

A 100 percent donation policy is now a defining characteristic of Charity: water. Harrison realized there was a deep mistrust of charities: People didn’t necessarily know whether their money was going to support the cause or the bureaucracy of a non-profit. So he decided to commit Charity: water to have every penny of the money the public donates go to building wells and bringing clean drinking water to those in need. The organization even reimburses credit card processing fees for those who charge a donation. It also emails donors letting them know exactly where their money was used.

To accomplish this, Harrison needed to finance the operations of the non-profit via a completely separate pipeline. Today, the philanthropy’s operations are funded by 125 families who are part of a program called The Well. The members, who came to Harrison through asks and referrals, donate between $60,000 and $1 million dollars per year for a minimum of three years.

In its first full year of operations, Charity: water raised $1.7 million. In 2017, Charity: water raised over $50 million. In total, Charity: water has raised more than $300 million. (The figures represent total money raised, covering both water projects and operations.) Over one million people have donated to Charity: water.

But despite Harrison’s early enthusiasm and success, the non-profit almost died in 2008. Harrison had more than $800,000 in the bank to build wells but he was within weeks of running out of money to make payroll and pay overhead. Friends recommended he borrow money from his well-building fund to pay his operations expenses, but Harrison refused.

“I remember being so outraged at that idea,” says Harrison. “I was going to shut the organization down and say that 100 percent model just didn’t work.

“And at that moment, a complete stranger walked into our office at 150 Varick Street at that time, sat with me for two hours, and then wrote a million dollars check to overhead,” says Harrison. “We went from almost bankrupt to 13 months of funding on the over head side.”

That stranger was Michael Birch, the founder of social networking platform Bebo, an early competitor to MySpace and Facebook. In 2008, AOL bought Bebo for $850 million cash. Harrison had written Birch a cold email six months earlier trying to spread the word about people using their birthday as an opportunity to raise money for Charity: Water. The non-profit calls this “donating” your birthday.

The phenomenon eventually got celebrity attention: Will and Jada Smith donated their birthday in 2010 and raised more than $109,000. In 2011, Justin Bieber donated his 17th birthday. Kristen Bell donated her 30th birthday in 2010, and Jessica Biel donated her 29th birthday in 2011.

In one particularly powerful story, Rachel Beckwith heard Harrison speak a few months before she turned 9 and told her mom she wanted to raise $300 for Charity: water to celebrate her birthday. She raised $220. A few weeks later, in July 2011, Beckwith was tragically killed in a car accident. Her story spread and strangers started donating to Beckwith’s campaign. In total, 31,997 donations were made to Beckwith’s campaign raising almost $1.3 million. The money gave access to clean water to 37,770 individuals.

Today, Charity: water has 73 employees, 71 of whom are in its New York City headquarters, and is employing another 1,250 workers in the 16 countries where it’s currently building water projects. Charity: water partners with local organizations in each country.

A large portion of Harrison’s time is spent cultivating the relationships with the families who donate significant amounts of money to the operations fundraising pipeline. He also spends a lot of time traveling and giving speeches. He makes 150 speeches a year, he says.

Since his days promoting clubs and partying all night, Harrison’s life has changed epically. He’s married (his second employee, Viktoria, became his wife) and he has two kids — Jackson, 3, and Emma, 18 months.

He’s never gone back to his old way of life.

“I had a very clean break with the vices, so before I set foot on the Mercy Ship, I had my last cigarette. So, I never smoked again. Never gambled again in my life. … I completely cleaned up my life,” says Harrison.

And though he’s brought clean water to millions, when asked to reflect last year, Harrison says, “I can’t believe how little we’ve done — that’s the real honest answer.

“So you know maybe that’s good,” adds Harrison, “because in year 11, I am like, ‘Well, we have got to get there,’ you know?”

Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

Patrick McGee: Tesla’s Robotaxi Bait and Switch

Elon Musk called self-driving cars a ‘solved problem’ 10 years ago. So how come he’s still working on it? In a new column, Patrick McGee…

Thought Leader: Patrick McGee

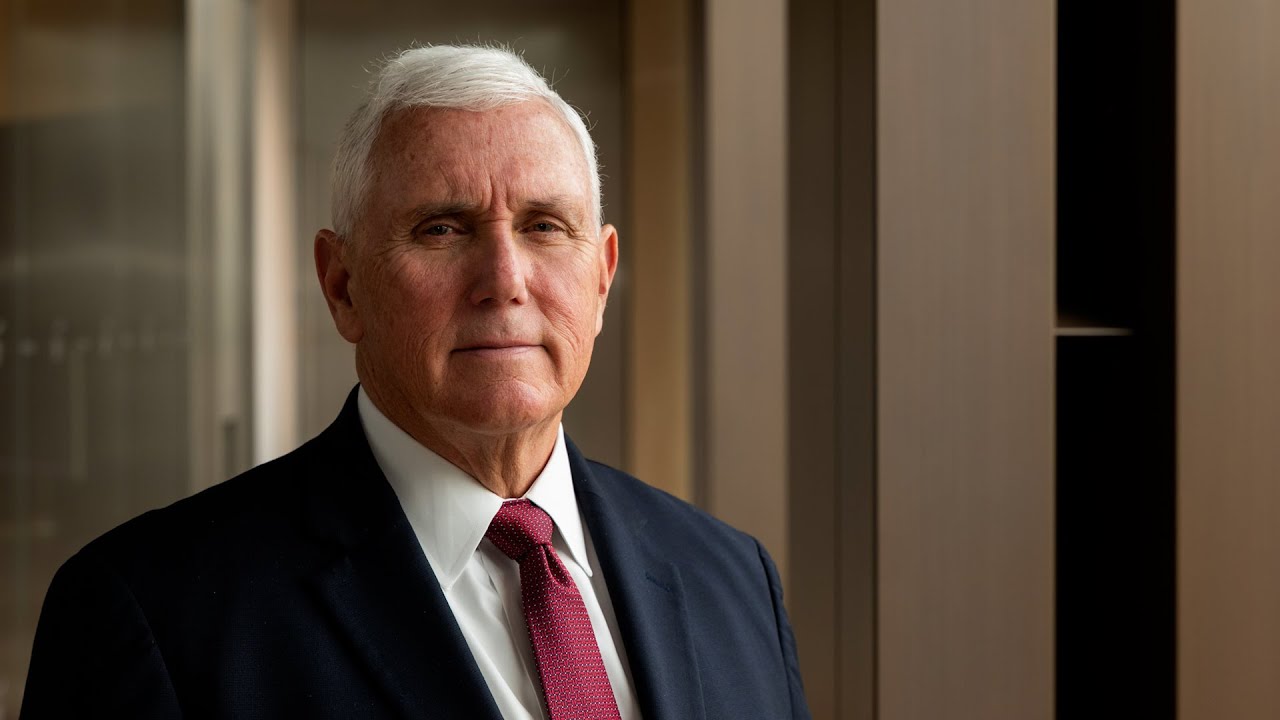

Mike Pence on U.S. Leadership and Global Strategy

Former Vice President of the United States, Mike Pence, shares his thoughts about President Trump’s framework on trying to acquire Greenland, and discusses what he…

Thought Leader: Mike Pence