Dr. Sanjay Gupta: Should You Eat Before or After Strength-Training?

Strength training can be confusing enough on its own. But mix in what —and when— to eat, and you might just choose to sit on the couch…

Thought Leader: Sanjay Gupta

Congress is considering two measures that modernize tools the Food and Drug Administration uses to oversee two areas of its vast portfolio: diagnostic tests and cosmetics. While the stakes are different for each of these industries, the basic premise driving these measures is the same.

The FDA is currently working from an outdated regulatory playbook that has left gaps in its oversight of safety and effectiveness and makes it more difficult to introduce new innovations. The new legislation would strengthen protections for consumers and patients for both diagnostic tests and cosmetics, and make it easier for manufacturers to introduce better products.

The provisions are being considered as policy riders to the spending bill that would fund the federal government for next year. It has taken almost two decades of debate and compromise to hammer out bipartisan proposals for these modernizations that have met the approval of most stakeholders. If these measures don’t pass now, it may take many years, along with many more setbacks and side effects, before there’s enough political momentum to get them this close to the finish line.

The legislation governing diagnostics, Verifying Accurate Leading-edge IVCT Development Act, or VALID Act (S. 2209 and H.R. 4128), modernizes the FDA’s program for overseeing diagnostic tests that are used to screen blood and tissue. Diagnostic technologies have undergone considerable advances in recent decades, owing to innovation in fields like genomics, proteomics, and data science. Sophisticated tests that screen for genes, proteins, and other markers are helping doctors make diagnoses that often went unrecognized just a short time ago, or would have required far costlier, riskier, and more invasive testing to ascertain. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 70% of health care decisions are based on clinical lab tests. The potential for the future is even greater, with early detection and better treatment guidance, and opportunities for new targeted therapies that will be guided by diagnostic markers.

However, the existing laws governing FDA’s regulation of lab tests to make sure they produce accurate results and can be used reliably as a part of medical practice have not kept pace with these advances. The outdated framework has forced the agency to regulate a test based on where it is made — by a medical device manufacturer, for example, or in an academic or clinical laboratory — rather than its distinctive complexity or potential risks. The result is an obsolete and bifurcated approach that leaves patients and providers often overestimating the amount of oversight that’s been applied to tests that matter for increasingly important clinical decisions, and that leaves test developers facing both uncertainty and inefficient regulatory burdens.

The FDA currently uses its old authority over medical devices to regulate tests made by commercial manufacturers and packaged as kits or dispensed outside the labs that created them. For tests that are manufactured by the lab that administers them, however, the agency has exercised “enforcement discretion,” owing to a prior dispute about whether these tests were a medical device subject to FDA’s oversight, or a service being delivered as a part of the practice of laboratory medicine. While it has generally been agreed for years that lab-developed tests are devices and therefore also subject to FDA’s regulation, the agency’s posture of enforcement discretion has left it without an efficient approach — and a clear mandate — to oversee most of these products.

As a result of this bifurcated regulatory scheme, the level of regulatory assurance of a test’s quality and reliability turns on where it was developed — a reality that many consumers don’t realize. When tests are faulty and unreliable, their results have led to misdiagnoses or bad treatment decisions.

The VALID Act would create a consistent standard for all tests, regardless of the kind of facility they were developed in or made in, as well as a modern regulatory framework that’s uniquely designed for the recent and emerging technologies being used to develop tests. It allows FDA to provide a consistent and efficient level of oversight that’s based on risk and complexity, and how a test is being used, rather than where it was manufactured.

The act’s novel regulatory approach largely takes the tests out of FDA’s existing structure for overseeing medical devices, and instead creates a new framework uniquely tailored to diagnostics.

Recognizing that test makers often market multiple tests that have much in common, and sometimes make frequent modifications to existing tests, the FDA would oversee the methods used to develop the set of tests and certify the rigor of that process, rather than regulate each test as a standalone product. Under this “firm-based” approach, test developers that have a thorough process for ensuring the reliability of their tests would, in many cases, be able to market new tests and update their existing tests without undergoing the same pre-market review in every case. This approach, which applies to moderate-risk tests, would make introduction of new innovations far more efficient.

The modernizations offered in the VALID Act would also enable more oversight to move to the post-market setting when appropriate. Right now, all new tests are automatically deemed as Class III — posing a high potential risk if inaccurate — and are subject to FDA’s most stringent requirements for a Premarket Approval application unless they’re reclassified, which can be an arduous process for a new test to navigate. Under the proposed act, the FDA would have more flexibility to adjust its approach to regulation based on risk, and down-regulate lower risk tests to moderate- or low-risk categories.

Existing lab-developed tests, including those assembled and used by academic medical centers, would be exempted so they wouldn’t face new regulatory authorities. New lab developed tests would be given a five-year phase-in period to come under FDA’s oversight. The new framework would also allow labs to continue to offer tests for rare diseases without unnecessary new burdens. Labs could modify a test or develop a new one for unique or unusual circumstances, or for use in low volumes, without seeking clearance by FDA. There’s also an “accredited persons program,” in which state regulatory programs can become third-party reviewers that stand in for the FDA.

Some academic medical centers have raised concerns that VALID could interfere with how they deliver care, because they often tailor tests to meet the needs of their affiliated providers. We believe that VALID’s risk-based framework has taken these concerns to heart and has balanced the need to foster innovation and give providers discretion with the goal of protecting patients. The VALID framework has many exemptions to ensure academic medical centers can continue to meet patient needs.

If VALID doesn’t pass now, the FDA has signaled it would start actively regulating all lab-developed tests by issuing a regulation that would declare them subject to the provisions of its existing medical device review process. This ill-fitted process would be far less efficient than what VALID prescribes, and the uncertainty about how it would be applied would thwart investment and innovation.

The FDA’s approach to cosmetics is also plagued by some of the same challenges. It was created by a framework tailored to an older generation of products that encompassed less innovation, but also fewer risks. Today’s cosmetics are more diverse in how and where they’re made, and how they act on the body. Many cosmetics contain advanced ingredients that offer consumers a broader set of opportunities, but that can also contain unwanted and sometimes dangerous contaminants.

The new cosmetics legislation allows the FDA to recall products that are found to contain ingredients likely to cause serious harm when companies don’t do so voluntarily. It would also require manufacturers to disclose the ingredients they use, and to follow good manufacturing practices.

When cosmetics firms are made aware of serious adverse health events, they would have to report them to FDA. As with diagnostic tests, consumers probably believe their cosmetics already meet these basic requirements and overestimate the scope of FDA’s existing protections.

These two proposals are close to passing, but the opportunity could still be lost. If that window closes, it may take many more reports of bad outcomes, and more proof of lost innovation from outdated regulation, to reach a point where these needed reforms will be this close to passage.

Scott Gottlieb is a physician, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and was commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration from 2017 to 2019. Mark B. McClellan is a physician, director of the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy at Duke University, and was FDA commissioner from 2002 to 2004. Gottlieb serves on the boards of Illumina, Pfizer, and Tempus Labs; McClellan serves on the boards of Alignment Health Care, Cigna, and Johnson & Johnson.

Dr. Sanjay Gupta: Should You Eat Before or After Strength-Training?

Strength training can be confusing enough on its own. But mix in what —and when— to eat, and you might just choose to sit on the couch…

Thought Leader: Sanjay Gupta

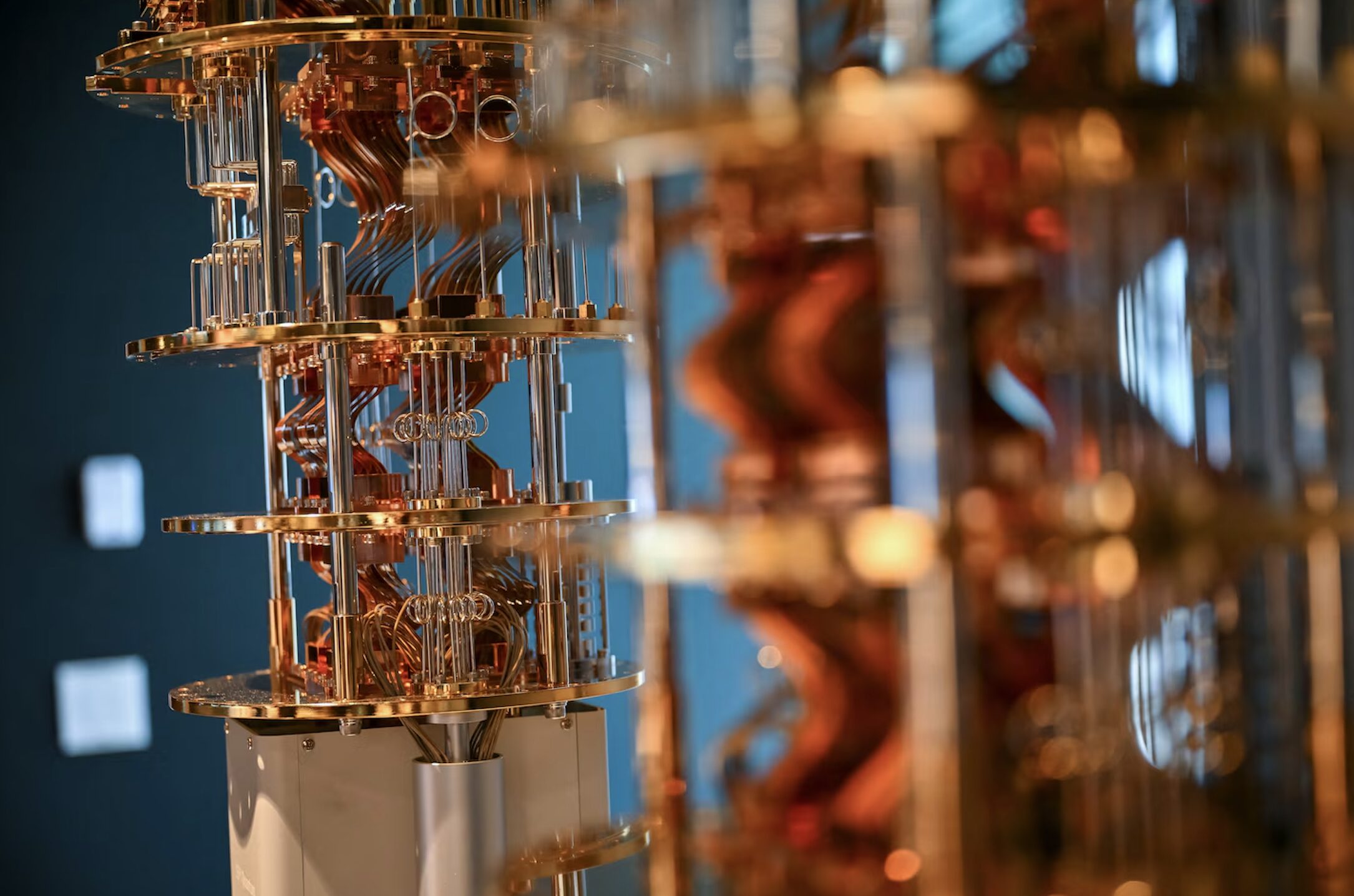

Chris Miller: The Supply Chain Risk to U.S. Quantum Leadership

The winner of the race for the futuristic tech could be determined by supply-chain bottlenecks. In this Washington Post analysis, Chris Miller and Josh Zoffer…

Thought Leader: Chris Miller

Alex Honnold Completes His Free Solo Of Taipei 101

ALEX HONNOLD AFTER COMPLETING HIS FREE SOLO OF TAIPEI 101. The 101 story climb took 1 hour and 31 minutes. Alex Honnold is a professional rock…

Thought Leader: Alex Honnold