David Frum: Voting Against Trump

Notorious RINO and Atlantic writer David Frum joins Jamie Weinstein to explain why he’s voting for Kamala Harris this election. Frum, a former speechwriter for President…

Thought Leader: David Frum

Twenty years ago, the National Quality Forum identified a list of medical “never events,” such as leaving a sponge inside a patient after surgery or operating on the wrong limb. These never events were preventable adverse events that indicate a severe problem with the quality or safety of care. The medical never events and patient safety movements galvanized institutions around the notion that some outcomes are unacceptable, overturning the notion that such harms were inevitably “a cost of doing business” in hospitals.

At the same time, hospitals have increasingly engaged in another set of behaviors that harm patients. For example, some hospitals have aggressively collected medical bills from patients who could not afford them, such as the 21-hospital Providence system, which, according to an account in the New York Times, hired “debt collectors to pursue money from low-income patients who should qualify for free care.” And an estimated 72% of private nonprofit hospitals had “a fair share deficit” in 2021, meaning they spent less on community benefit than the estimated value of their tax exemption status, ranging from thousands of dollars to hundreds of millions.

Hospitals should be places for healing, not agents of harm—and there is precedent for addressing harm in hospitals. Now, another category of hospital behaviors should be rendered unacceptable—a different set of never events. Five are especially harmful.

First, hospitals should never pursue aggressive debt collection tactics against patients who cannot afford their medical bills, such as suing them,1 garnishing wages, placing liens on homes, and denying care due to owed debt.2 Second, a hospital should never spend less on community benefits (such as providing care to uninsured patients or funding public health programs) than it earns in tax breaks from its nonprofit status. Third, hospitals should never flout federal requirements to be transparent with patients about the costs of their care. Fourth, hospitals should never provide compensation worth less than a living wage for hospital workers, such as janitors and food-serving employees. Fifth, a hospital should never deliver racially segregated medical care, whereby it systematically underserves its surrounding communities of color.

The effects of these hospital never events are often more subtle than those of medical never events, which may contribute to widespread acceptance and normalization of hospitals implementing these practices. Other organizations, such as insurance companies and medical device makers, undoubtedly create harms of their own that merit dialogue. But the fact that the majority of hospitals are engaged in 1 or more of these 5 behaviors, and the possibility that rising costs at some hospitals may exacerbate these practices, necessitates attention.

Consider that despite billions of dollars in tax breaks, 60% of nonprofit hospitals over the past several years spent less than 2 cents on charity care for every dollar of net patient revenue, according to a July 25, 2022, Wall Street Journal article that included an analysis of recent Medicare cost reports. This reality has coincided with a growing financialization of hospitals. Hospitals have pursued mergers or acquisitions that enable higher hospital prices but often no discernible improvement in quality for patients.3 In addition, although many hospital workers struggle to get by, some executives have benefited comfortably—as highlighted by an account of a technician in Missouri who was earning $30 000 annually at a hospital that paid its CEO about $30 million in compensation. In many areas, affluent hospitals are more likely to treat patients who are White, even if the surrounding community comprises people from racial and ethnic minority groups, such as Black and Hispanic patients, who are more likely to be cared for in cash-strapped safety-net hospitals.

Some may argue that eliminating administrative never events adds another burden to hospitals, arguably institutions already delivering significant social good. To the contrary, preventing administrative never events can bring needed clarity to hospitals’ roles. Private hospitals have expanded their purview to include addressing patients’ social drivers of health, spending billions of dollars by providing resources such as assistance with housing or establishing food pharmacies.4 Although such programs can be beneficial to patients, it is now possible for a hospital to provide one patient a free taxi ride to overcome transportation barriers and simultaneously sue another patient for medical debt. Hospitals’ first responsibility should be to stop creating social harms.

Across the country, individuals and organizations have laid the foundation to address hospital never events. Researchers at the Lown Institute ranked hospitals on outcomes, value, and health equity.5 Their work revealed the harms obscured by traditional hospital rankings; they observed that 17 of 20 hospitals ranked highly in the annual ratings from US News & World Report received a grade of “C” or lower on their equity metric, a metric that captures community benefit investments, patient inclusivity, and pay equity. At the same time, the Lown Institute spotlighted hospital systems rating highly in social responsibility, such as Boston Medical Center, which ranked overall among the top 4 hospitals nationally based on its inclusivity, investments in community health, and outcomes.

Frontline workers also have spoken up. For example, a coalition that included patient advocates, consumer rights proponents, lawyers, health care workers, and people directly affected by medical debt voiced their support of a proposed law to address medical debt in the state in testimony before the House Health and Government Operations Committee of the Maryland General Assembly. One speaker, a registered nurse, testified that his “patients should be focusing on healing from trauma, not on worrying about medical debt or the hospital suing them to collect.” Various organizations are working to reduce or end medical debt, which now constitutes 58% of all debt collection actions across sectors. Such action has laid the groundwork, but these steps alone are unlikely to bring about swift change.

Hospitals themselves can address never events, just as visionary hospital leaders were part of the campaign to end medical never events. However, eliminating these practices also calls for policy action. In the same way the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) authorized Medicare and state Medicaid programs to deny payments for medical never events, the CMS could adjust payment for those engaged in egregious administrative practices. State legislatures could require reporting of hospital never event practices and incentivize changes. For example, earlier this month, Colorado banned hospitals from collecting patient debt if the hospital is not complying with price transparency rules. And state attorneys general could investigate hospitals that are using these practices to take advantage of patients and their nonprofit status. These actions can occur alongside efforts to fix the nation’s antiquated health care reimbursement system, as reforming the incentive structures causing hospitals to maximize revenue at the expense of patients is the ideal long-term solution.

During the most intense waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, the people who work in hospitals, including administrators and clinicians, have demonstrated their exceptional capability to serve people in a time of need. Even during normal times, people come to the hospital seeking care from clinicians who exercise their best judgment based on years of training and the central teaching from Hippocrates, “First, do no harm.” Patients deserve the same expectation of no harm from the policies of the hospitals that care for them.

David Frum: Voting Against Trump

Notorious RINO and Atlantic writer David Frum joins Jamie Weinstein to explain why he’s voting for Kamala Harris this election. Frum, a former speechwriter for President…

Thought Leader: David Frum

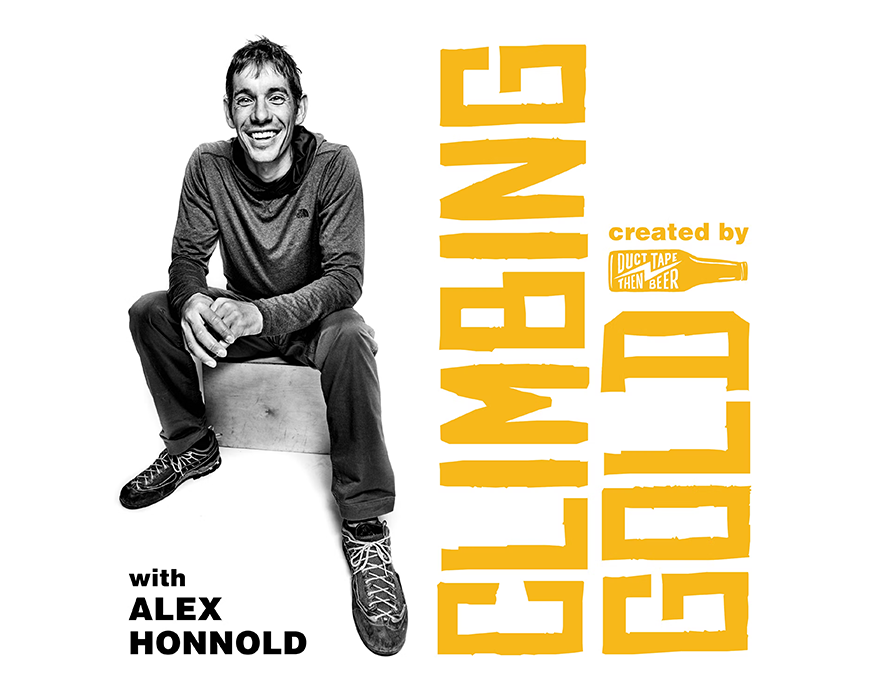

This is the latest episode of Climbing Gold with Alex Honnold. Tucked away in a corner of Chilean Patagonia, Valle Cochamó wasn’t going to stay hidden…

Thought Leader: Alex Honnold

Sanjay Gupta: Self-Exams Matter

This is the latest episode of Chasing Life with Dr. Sanjay Gupta. Sara Sidner is a hard-hitting CNN journalist. Ananda Lewis is a content creator and former…

Thought Leader: Sanjay Gupta