Dr. Sanjay Gupta: A New Way to Heal

Doctors have long prescribed pills and procedures. But for some people, that isn’t enough. Sanjay sits down with Julia Hotz, author of The Connection Cure, to explore the…

Thought Leader: Sanjay Gupta

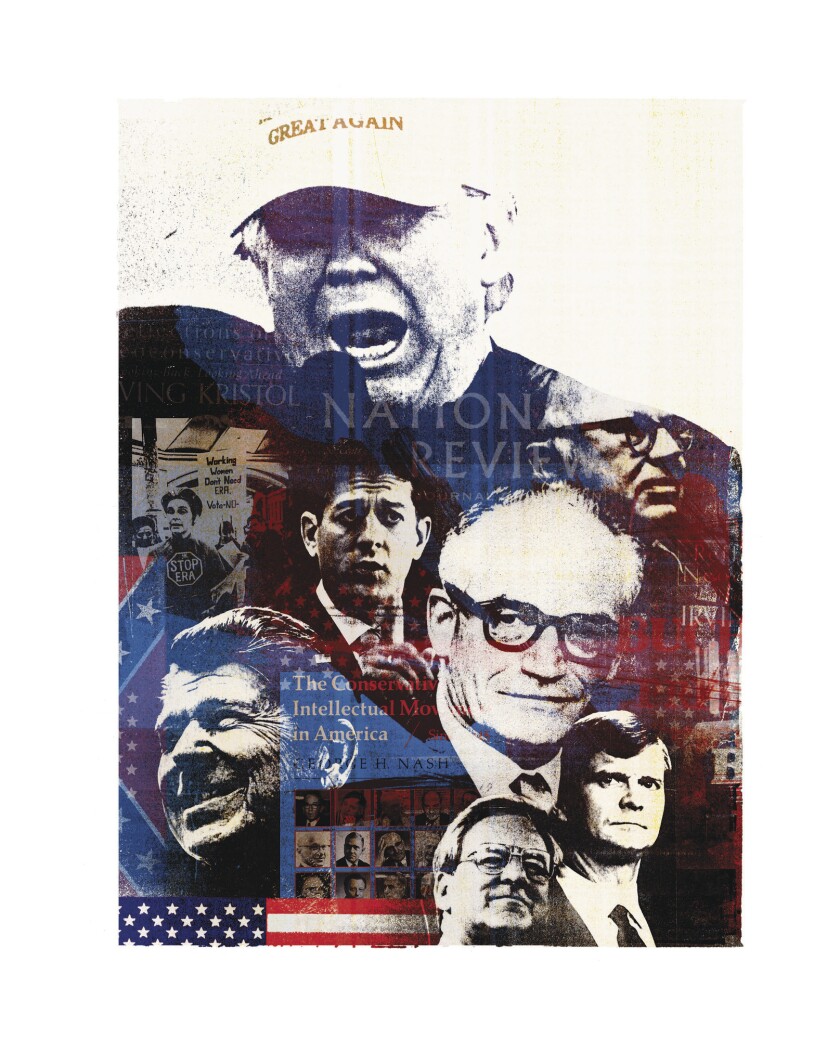

t might be preposterous in this, the year of Trump, to even think about conservatism as an intellectual movement. Trump’s unexpected rise seems to lay bare a simple fact — that conservatism has not only lost the battle of ideas but ceded the terrain of sophisticated thought altogether.

But a deeper understanding of the intellectual currents that have coursed beneath modern conservatism is essential to explaining why those currents now appear to have dried up. Ever since George W. Bush declared Jesus Christ to be his favorite political philosopher, Republican presidential candidates have competed in a sort of anti-intellectual sweepstakes, each seeking to outdo the others in disavowing science, higher learning, and any deliberate cultivation of the mind. How did a movement once defined by intellectual intensity become so hostile to ideas?

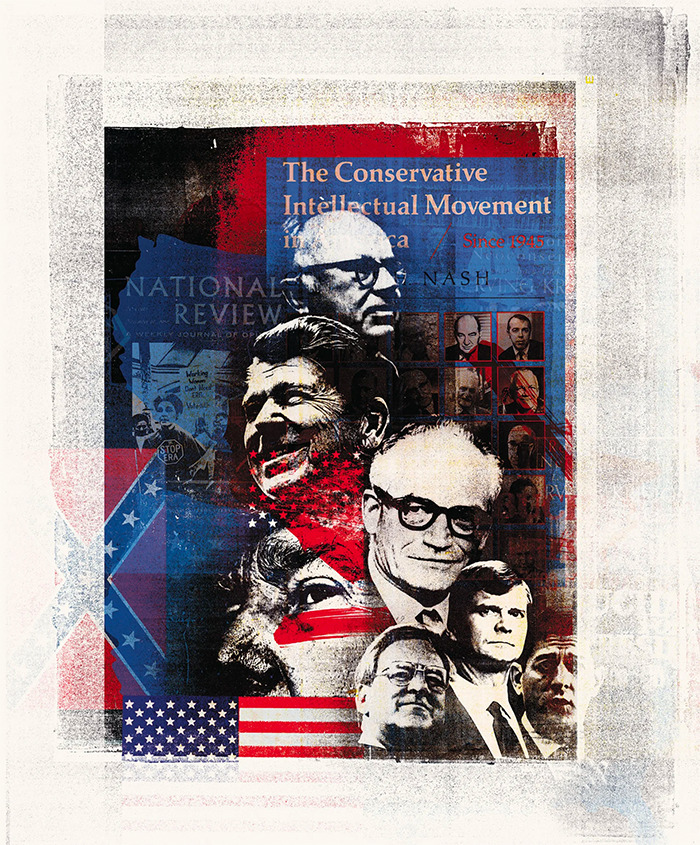

As it happens, the year of Trump also marks the 40th anniversary of a book that has done as much as any work to explain American conservatism. In 1976, a Harvard Ph.D. named George H. Nash came out with The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945. The book may not be well known to general audiences. But for scholars then and now, it has been foundational, one of those rare works that didn’t just say something new but opened up an entire field of study.

Nash presented an influential portrait of conservatism as a river fed by three tributaries of thought: Christian traditionalism, anti-Communism, and libertarianism (or classical liberalism). Although each could be rendered as a popular impulse or unthinking reflex of the mass mind, Nash insisted that all three were fundamentally intellectual traditions, nourished by a cast of characters who deserved both respect and extended study, among them James Burnham, the former socialist turned anti-Communist; Friedrich Hayek, the Austrian classical economist; and Russell Kirk, America’s answer to Edmund Burke. In Nash’s telling, these were the men (and they were almost all men) who created conservatism in the postwar years.

Nash’s book illuminates a central reason for conservatism’s historic success, and its recent failures.

Where is conservatism today? Once an anguished response to war and chaos, religious traditionalism has become just another sort of identity politics; anti-Communism informed by classical liberalism is now recrudescent nativism; and countercultural libertarianism has hardened into market fundamentalism. The evolution has reached its apogee in Donald Trump, a man singularly devoid of ideas and proud of it. To be sure, classic conservative thinkers persist, but their voices are dim, like light from a dying star.

Nash’s intellectual history illuminates a central reason for conservatism’s historic success, and its more recent failures. Like the conservative movement itself, Nash’s book was animated by a fundamental tension. In his telling, conservatives at once accepted a range of ideas into their universe yet simultaneously erected boundaries to create a consistent (and electorally viable) ideological identity. Nash’s book gives us the first part of the story, describing how conservatism succeeded by purging bad ideas and dangerous impulses. But it could not follow the denouement: when conservatism ossified into orthodoxy, leaving it defenseless before Trump’s onslaught.

There is truth in the conservative intellectuals’ claim that Trump hijacked conservatism. It is also true that despite its principled origins, conservatism birthed Trump.

How did the arc Nash described end with a dive toward a proudly ignorant populism? When I reached Nash at his home in South Hadley, Mass., in August and posed that question, it was clear he’d given the matter a good deal of thought. Well schooled in the perennial divisions among conservatives, Nash saw in the GOP primary a new era — basically a “civil war” on the right.

Trumpism was, unquestionably, “a rebellion against the movement I wrote about,” Nash told me. What seemed to astonish him, however, was that Trump was not just going after the eggheads. “Historically there has been a distinction between the GOP apparatus” — meaning the party establishment in Washington — “and the intellectual conservative establishment,” Nash noted. “Trump has gone after both establishments.”

The current crisis has boosted Nash’s profile as a wise man of conservatism. He’s been busy on the lecture circuit, has written a well-regarded piece on “The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America: Then and Now” for National Review, and recently published an essay for The New Criterion on the problem of populism.

It’s a fitting turn for a man who literally wrote the book on conservatism — far before it was fashionable to do so. In 1976, Nash’s expertise on conservative thought made him a scholarly oddity. A generation earlier, in the time of McCarthyism and then Barry Goldwater, the subject had enjoyed a brief vogue of attention from high-profile scholars like Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and Richard Hofstadter. Both had been scathing: American conservatism was “pseudo-conservatism,” or a movement driven by “status anxiety” and other pathologies.

Nash’s sympathetic attention to conservative ideas put him “out of the groove” at Harvard, he recalled. But he didn’t go unnoticed: The trade publisher Basic Books pursued his manuscript eagerly, correctly anticipating it could reach an intellectual public readership. And his respectful treatment of conservatism would prove more durable than the earlier polemical literature he implicitly challenged.

Forty years later, the intellectual history of the right is a rich and vibrant field, built largely atop Nash’s keystone text. My own work is a case in point. My first academic article was a lengthy critique of Nash; my first book, Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right, grew out of a paragraph in his tome; and the book I’m writing now, on Milton Friedman, could also be seen as a response to ideas Nash first put down on paper.

I’m far from alone. From Angus Burgin’s prize-winning The Great Persuasion (Harvard University Press) to Kimberly Phillips-Fein’s Invisible Hands (W.W. Norton) to popular works like Jane Mayer’s Dark Money (Doubleday), Nash’s legacy as the first historian to legitimate conservative ideas as a force in history can be felt to this day. Almost all of the obscure thinkers and organizations whom Nash name-checked — including Richard Weaver, Young Americans for Freedom, and Phyllis Schlafly, to name a few — now have their own biographies or full-length studies.

The primary theoretical innovation behind Nash’s book — and the reason it became a staple of both graduate-school reading lists and conservative book clubs — was that he chose to sidestep arcane debates about who was a conservative and who was not, and instead took a “big tent” approach to conservatism. Earlier commentators — all unfailingly liberal — had exhausted themselves arguing that American conservatives weren’t really conservative, not like Tories or monarchists or proper capital-C Conservatives. After making the point, they had little else to add.

By contrast, Nash described how conservatism really functioned in the drawing rooms, little magazines, and epistolary clashes that formed its core at midcentury. What his analysis made clear was that the kaleidoscopic, even contradictory nature of conservative thought was among the movement’s greatest strengths. Who cared if fighting off Communists might expand the state in a way that small-government libertarians found abhorrent? Could unfettered capitalists also be their brothers’ keepers? Hashing out these quandaries was an essential part of joining a living, breathing ideological movement.

Yet critically, conservatism had a pale. The hero of Nash’s account was William F. Buckley Jr., an entrepreneur of ideas who brought conservatism’s fractious voices into common cause. Presiding genially over all of this intellectual ferment, Buckley used his flagship magazine, National Review, to purge conservatism of its most damaging shadow side: anti-Semitism. He cast out the conspiracy theorists, cranks, and malcontents who had dominated the conservative reaction against Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Buckley then focused the movement on two common enemies: domestic liberalism and international Communism.

The kaleidoscopic, even contradictory nature of early conservative thought was among its greatest strengths.

With Buckley at the helm, conservatism emerged as a thinking man’s creed, ready with robust, counterintuitive arguments about the unintended consequences of well-meaning social policies, hard questions about national security, and vigorously debated theories about the relationship between government and growth. To be a young conservative in the 1950s and ’60s meant mastering an elaborate canon of political philosophy, economics, and social thought, or arguing the nuances of Objectivism late into the night, all the while dreaming of the day these ideas would power a campaign or think tank. It was this heady atmosphere that David Brooks, who came into conservatism in the ’80s, wistfully recalled in a recent elegiac column, “The Conservative Intellectual Crisis.”

Conservatism wasn’t wholly rid of its noxious aspects. On race, Buckley was far from a trailblazer, as his notorious 1957 National Review editorial declaring white Southerners “the advanced race” made clear. And Buckley’s conservatives had little to say about the roles that women or nonwhite people might play in their movement. Conservatism remained mostly a white, male creed.

To understand what’s happened to conservatism, we have to pick up the story where Nash left off in 1976. If there was ever a time when the phrase “conservative intellectual movement in America” seemed far from parody, the mid-1970s were probably it. By then the liberal political and economic consensus that had defined America and Western Europe since World War II was showing signs of decline. When inflation, stagflation, oil shocks, a failed war in Vietnam, and the pressures of emergent globalization began to derail the decades-long run of prosperity that Americans had enjoyed, the nation was ready for new ideas.

The 1970s were unquestionably a time of conservative intellectual dominance. An influential flank of academic liberals broke right and became “neoconservatives.” Keynesian economists were suddenly on the defense, in universities and policy circles, as monetarism and price theory rose to prominence. Public-choice scholars doubted the very idea that politicians might work on behalf of a common good; sociologists pried beneath the surface of social-welfare programs to question their efficacy; law professors challenged the courts to think through the costs and benefits of every ruling. Think tanks proliferated; business groups lobbied to defeat regulation; even libertarians organized themselves into a political party.

In such a climate, Nash’s story of a movement driven by ideas, defined by intellectuals, and destined for national greatness seemed more than plausible. In the years after his book appeared, the infrastructure he described flourished and expanded. At the same time, Nash’s work became increasingly important to scholars, even though he decided not to pursue a career in academe. (Nash explained this as a deliberate choice, telling me he turned down a tenure-track job offer, accepting instead a commission from a private foundation as Herbert Hoover’s biographer.) Today most intellectual historians of 20th-century America can recite the basics of Nash’s thesis: the three strands of conservatism, their unsteady “fusion” under the guidance of National Review, and the importance of anti-Communism as a sort of ideological glue.

But does Nash’s synthesis still hold true? What spurred scholarly fascination with conservative intellectual life was how it connected directly to a political movement nested within the Republican Party. How rare it was to find a group of serious thinkers whose ideas landed in the Oval Office or made cameos in the State of the Union. Yet today the most obvious political progeny of the movement Nash defined — nationally known conservatives like Paul Ryan, Mitt Romney, and Jeb Bush — struggle to remain relevant. How does Nash account for this development?

Were his book published today, Nash tells me, he would modify his thesis in the following ways. He’d add two elements to the conservative movement, neoconservatives and the religious right, both of which came to prominence in the 1970s. He’d position Ronald Reagan as the ecumenical figure who continued Buckley’s project of conservative unity through the 1980s. And he would emphasize the ending of the Cold War, which removed a sense of common cause and allowed the various factions of conservatism to again cultivate their own gardens. (Some of these ideas were reflected in a 1996 edition of his work, published by the conservative ISI Books.)

Other elements at play, according to Nash, involve the emergence of new media technologies and the “perils of prosperity,” both with their own centrifugal forces. Nash also fingers the Pat Buchanan paleoconservatives of the 1990s as the forerunners of Trumpism. Nash argues, essentially, that the process he described in his book has been reversed by the passage of time and the impact of new technologies. If conservatism succeeded by clearly demarcating the line between insiders and outsiders, today that is no longer possible. As he wrote in The New Criterion, not only are there no more gatekeepers like Buckley, “there are no gates.”

For the most part, I agree with Nash’s story, but I’m struck by two elisions. One is the near absence of race and gender in his account. Nash does acknowledge the white-supremacist elements of Trump’s rise, and is particularly critical of the alt-right, but he believes it to be a fringe movement magnified disproportionately by the internet. “I’m quite willing to say as a historian, if we analyze changing voting patterns and so forth, race has to be taken into account,” Nash told me, “but there are other things happening that explain political transformation. What I oppose is reductionism. I don’t see conservative ideas as a thin veneer over an ugly id.” Nash also has little to say about the vicious and gendered attacks upon Hillary Clinton, another decades-long conservative tendency. Whatever conservatism is conserving, white male privilege is not foremost among the elements Nash would emphasize.

The other lacuna is how little globalization or other economic and structural forces factor into Nash’s account of historical change. At times the crash of 2008 figures into his new narrative. But he glosses over the policy responses to the crash itself — the creed of “too big to fail,” even as small homeowners go under; the bailouts of politically connected financiers and banks; the absence of legal accountability despite clear evidence of fraud or negligence — as explanations for Trumpism. Nor does he emphasize increasing economic inequality as an emergent challenge that both conservatives and liberals have found difficult to meet.

I asked Nash directly if the conservative synthesis may have run its course. “There is some reason that the natives are restless,” he says. Some of this, he thought, might be chalked up to “talk-show types” who failed to emphasize the slow and incremental nature of change in a mass democracy with power divided between two political parties. Nash also thought it clear that Paul Ryan, “with his views on trade and immigration and entitlement reform, is not where the party base is at present.”

But his prescription for conservatives is to go back to that holy trinity of postwar conservatism, abstracted out into freedom, virtue, and safety, and then to build again from that base. He’s not willing to go as far as some other conservative observers, such as Ross Douthat, who recently enumerated “What the Right’s Intellectuals Did Wrong.” The fundamentals, for Nash, remain solid.

The 30 years of conservative emergence that Nash documented in his book occurred against a backdrop of global transformations as unsettling as we’ve seen in our time. Yet conservatism weathered all those earlier tectonic changes with aplomb, even drawing paradoxical strength from instability. What has changed since is not the rate of social change but conservatives’ willingness to acknowledge and learn from it.

Most damaging of all, conservatives have lost the habit of critical thought. And they lost it well before Trump, somewhere around the time that conservatism passed from upstart to establishment. Perhaps it was inevitable, when careers could be made by reciting the party line, that the party line would become inviolable. Or perhaps it was a holdover from that never-quite-vanquished paranoid style, that deeply held belief, born in the New Deal, that conservatives were somehow permanent exiles from power.

Most damaging of all, conservatives have lost the habit of critical thought. And they lost it well before Trump.

But in the years after 1976, as conservatives ascended to national power, their skillful self-critique and intramural warfare gave way to a unified assault on liberalism. Of course a common enemy had always been important. But a sense of flaws lurking within, what the traditionalists might have called the consciousness of mankind’s fallen state, was equally important. And ironically, just as their ideas became more influential in academe, conservatives stopped caring about academic respectability. To question, to venture, to iterate or backtrack or ideologically evolve: these became markers of liberal relativism, not the messy quest for truth.

Undoubtedly, this is part of why Trump seemed so refreshing to primary voters. Just as an earlier generation of conservatives took aim at liberal insularity, so Trump’s gleeful provocations would not have gone over as well without a substantial quotient of establishment smugness as their foil. Nor could Trump’s racism and misogyny have gone down so easily if conservatives over the years hadn’t positioned themselves so explicitly against feminism and racial liberalism.

And so conservatism has been routed by Trumpism, a movement driven by all the resentments that the right has dredged up over the decades with none of the ideas that once animated it. As Nash put it, there is a “return of the repressed” at work in the rise of the alt-right, with all the ugliness that Buckley once purged now on full display at rallies and on the internet. Perhaps there is an intellectual core buried within the alt-right; if so, that world awaits its Nash.

It took scholars decades to fully embrace the insight at the core of Nash’s classic work: that over the course of the 20th century, the intellectual and ideological energy that had driven the left to great heights and even greater depths had shifted, and it was conservatives who came to command the high country of the mind. Unless conservatism experiences a renaissance that restores its original spirit of intellectual vitality, the same will not be true of the 21st century.

Jennifer Burns is an associate professor of history at Stanford University and author of Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Dr. Sanjay Gupta: A New Way to Heal

Doctors have long prescribed pills and procedures. But for some people, that isn’t enough. Sanjay sits down with Julia Hotz, author of The Connection Cure, to explore the…

Thought Leader: Sanjay Gupta

Niall Ferguson: Trump’s World Order Live From Davos

Live from Davos, Scott Galloway and historian Niall Ferguson examine why today’s geopolitical moment looks less like a “new world order” and more like a…

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

Mike Pence Talks Trump’s Foreign Policy

Former US VP Mike Pence discusses President Trump’s foreign policy with Greenland, Russia, and Ukraine. He says he commends President Trump on finding a framework…

Thought Leader: Mike Pence