Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

My first visit to Kyiv since the Russian invasion in February coincided with a major Ukrainian military success in the east of the country, where Kupyansk and Izyum were liberated and Russian troops routed. However, the government of President Volodymyr Zelenskiy is too smart to celebrate one successful battle when there is a war to be won against a still-formidable adversary.

In the belief that one of the geopolitical fault lines of the modern world runs through Ukraine, I have visited the country annually for the past 11 years to attend the Yalta European Strategy conference, or YES, an event organized by the Victor Pinchuk Foundation. A businessman and philanthropist, Pinchuk is indomitable. When Russia annexed Crimea (including Yalta) in 2014, he moved the event to Kyiv, but kept Yalta in the name. When Russia invaded again in February, launching a Blitzkrieg against Kyiv, Pinchuk insisted the event must go on. I and the other foreign participants traveled from Poland by an overnight train for two absorbing days of discussions and meetings attended by Zelenskiy and key members of his government.

Zelenskiy and his team are acutely aware that the next three months will bring both economic and diplomatic dangers for Ukraine.

Economically, the nation’s parlous fiscal and monetary situation is leading the country in the direction of high inflation if not hyperinflation. Diplomatically, the approach of winter and the shifting sands of European and American politics pose a threat to Western unity that the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, is hoping will give him leverage. Without an immediate increase in Western support, Ukraine will struggle to sustain its success on the battlefield.

The good news from the eastern front was conspicuous by its absence from the speech delivered by Zelenskiy at YES on Friday. A “winter of discontent” lay ahead not only for Ukraine but for all of Europe, he warned; the next 90 days of the war with Russia would be decisive.

In his speech and in subsequent discussions, Zelenskiy, wearing his trademark green T-shirt, made it clear that any kind of negotiated settlement with Russia is out of the question so long as Russian troops remain on Ukrainian soil. “There is no exit … but to win,” he declared. “If our generation cannot win this war of attrition in our lifetime, the fight will still go on.”

However, he also made it clear how urgently Ukraine needs not merely continued assistance from the US and the European Union, but more assistance. Europe must resist war fatigue, Zelenskiy insisted. “The choice is between prices and values” — an implicit acknowledgment that inflation is now an actor in the Ukrainian drama.

Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal struck a similar note. “This is the beginning, a very promising one,” he said of the successful counteroffensives east of Kharkiv. “But this news should not make us complacent … This demonstrates our will and our way to win this war.” Shmyhal was one of several Ukrainian spokesmen who explicitly acknowledged the risk of hyperinflation.

In a realist perspective, Russia would seem bound to prevail over Ukraine sooner or later. Its territory is 28 times larger; its GDP is nine times larger; its population is 3.3 times larger. Western sanctions do not alter the fact that Russia still has significant (if reduced) revenue from exporting its gas and oil, whereas Ukraine is heavily dependent on Western economic and military assistance. Time might seem to be more on Russia’s side than Ukraine’s.

But Russia could still lose. Size is not everything. Thirteen American colonies vanquished the British Empire. North Vietnam defeated the US. The Soviet Union could not win in Afghanistan. Empires decline and new nations break free.

The invader is at an inherent disadvantage in the face of a strong nationalist sentiment. Putin has inadvertently turned the formerly divided and disgruntled inhabitants of Ukraine into the Ukrainian people. And wars of national liberation against declining empires are more often successful than not. That is why there aren’t many empires left.

One may debate whether the US and the Soviet Union were empires between the 1940s and the 1980s (both denied it). What no one denies is that they waged a Cold War. That meant that World War III did not take place, but many proxy wars were fought in which one or more the superpowers backed one or more sides in regional conflicts.

Right now, Ukraine is not only fighting for its freedom; it’s a proxy for a US-led effort to weaken Russia (and perhaps also to deter China from similar aggression). The Ukrainian war effort is sustainable only thanks to large-scale military and financial aid from the US and its Anglosphere and European allies. At the same time, US-instigated sanctions (especially technology export controls) are driving the Russian economy and military back into the late 20th century.

This is an asymmetric war in Cold War terms. The combined resources of the countries actively supporting Ukraine vastly exceed Russia’s, while China has thus offered minimal support to Russia (though watch carefully this week’s meeting in Uzbekistan between Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping).

If the US further increased its supply of precision weaponry to Ukraine and added tanks to the mix, the Russian positions in Kherson, Luhansk and Donetsk could probably be made unsustainable. Similarly, if the EU further increased its economic support for Ukraine, the risk of an inflationary crisis would recede.

There is a scenario — I would give it a 20% probability — that the Russian position in Ukraine now unravels. This is a largely colonial army, its best battalions severely depleted by six months of highly destructive warfare, its ranks replenished by raw recruits from impoverished provinces east of the Urals. Its morale is low. Such armies can be brought to a tipping point if they encounter well-armed, well-organized and well-motivated opponents. Defeat in land war is much less about killing enemy soldiers than getting them to surrender, flee or desert.

The question in the scenario of a Russian collapse would be whether Putin was willing to risk direct NATO retaliation against Russia by resorting to tactical nuclear weapons or (an option less discussed but potentially more effective) strikes on Western satellites aimed at disrupting Ukrainian communications.

Because neither Washington nor Moscow wants to go head-to-head, I suspect Western assistance to Ukraine will continue at around the current level, ensuring that the war lasts not for just a few more months but for perhaps a year or more.

The war in Ukraine has now entered its seventh month. Most wars are shorter. Of 88 wars between states since 1816, nearly a quarter lasted less than two months and 38% between two and six months. Of the remaining 35, 12 were over within a further six months, seven lasted up to two years, 12 two to five years, and four more than five years.

In other words, a war that continues for six months has a roughly one-in-three chance of lasting no longer than a year in total, but an equal chance of lasting between two and five years. We should not forget the Korean War, the first “hot” war of Cold War I, which lasted three years and did not end with a conclusive peace agreement — merely an armistice.

The Ukrainian army may be winning. The Ukrainian economy is losing. As is typical in a war of this sort, the invaded country suffers a severe decline in output simply because productive land and assets are taken over by the enemy or destroyed. At the same time, one-third of Ukrainians have been displaced by the war; over 6.8 million have left the country and the rest are internally displaced. A large proportion have lost their jobs and homes.

Ukraine’s GDP shrank by 15.1% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2022. In the second, it shrank by 37%. The overall annual contraction of output will be around 33%, according to government estimates. Unemployment is at Great Depression levels.

The total damage caused by the war to Ukrainian infrastructure and housing was estimated last week in a World Bank report at $97.4 billion. The same report estimates total losses from the shuttering of business at $252 billion.

There are some signs of improvement. Oleksandr Kubrakov, the minister of infrastructure, confirmed that there has been a recovery of agricultural exports with ships sailing through the Black Sea again. German Galushchenko, the minister of energy, told the YES conference that Ukraine could potentially supply two gigawatts of power to the EU right now, but was being prevented from doing so by bureaucratic obstacles on the European side. But these are green shoots in a battlefield the rival armies have not finished trampling.

Although the Ukrainian government has an ambitious plan for the reconstruction of the country (price tag: $750 billion), it needs much more modest sums right now simply to stay afloat. As Shmyhal put it, “Infrastructure needs to be rebuilt before the winter in order for people to survive — I mean this literally.”

In the familiar pattern of an economy at war, public spending has soared while tax and other revenues have collapsed. Tax revenue in Ukraine now covers just 40% of government spending. The Finance Ministry says it requires approximately $5 billion (2.5% of pre-war GDP) in foreign aid per month to cover nonmilitary spending. To date, however, Ukraine has received $17.5 billion in aid, roughly half of the amount pledged by international partners — and far short of the government’s needs.

The Europeans are the main culprits. The EU promised Ukraine 9 billion euros in budgetary support in May, but only about 1 billion has been disbursed. The National Bank of Ukraine has had to buy roughly $8.2 billion in war bonds as the government dares not try to sell new debt on the international market so soon after “reprofiling” (i.e. delaying payments for two years) its existing external debt. Inflation, which began the year at 10%, is now at 24% and rising. The central bank has raised interest rates to 25% but it has also been obliged to devalue the hryvnia by 25% against the dollar.

A recent paper published by the Centre for Economic Policy Research urges the government to raise tax revenue and to sell domestic debt rather than monetize it through the central bank. I heard nothing in Kyiv to suggest this advice is going to be heeded. In the words of the Swedish economist Anders Aslund, “The greatest immediate risk to the Ukrainian economy is that the EU does not deliver sufficient budget support soon enough.” In that case, he added, the Ukrainian government “will be forced to print money so that the current high inflation … proceeds to hyperinflation.”

Andrii Yermak, the head of the Office of the President of Ukraine, has called for the “recognition of Russia as a state sponsor of terrorism by the United States and G7 countries,” calling that a “silver bullet for the Russian defense industry.” Such a move might also open the way to the confiscation of Russia’s international reserves, money that Kyiv covets for its own reconstruction needs. But Yermak and his colleagues cannot afford to wait for the US government to take such a momentous decision.

If one assesses commitments to Ukraine, the imbalance between US and EU support is not especially striking. Half of total assistance is American; 31% European. The UK and international agencies account for 7% apiece. But if one assesses only disbursements, it becomes clear that the Europeans are dragging their feet, as noted above.

The Ukrainian strategy is to guilt-trip Europeans into giving more money and expediting Ukraine’s accession to the EU, which Shmyal spoke of as being achievable within two years. The president of Latvia, Egils Levits, and the Polish prime minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, were among the European leaders present at the Yalta conference who pledged support for Ukraine. But none was as unequivocal as Jake Sullivan, the US national security adviser, who assured the audience that Washington was going to stick with Ukraine “for as long as it takes … and President Zelenskiy can take that to the bank.”

Total support for Kyiv from backers in billions of euros

Source: Ukraine Support Tracker

“Other EU” denotes countries with combined contributions of less than 0.4B euros

The Russian economy is clearly faring better than the Ukrainian — after all, very little damage has been done on Russian territory. The budget remains in surplus for 2022 thus far, though it recorded a substantial deficit in July. After initially nose-diving in late February and early March, the Russian ruble has since strengthened.

However, things may be worse than at first meets the eye. Though oil revenue remains comparatively high, revenue from taxing natural gas sales has plunged. At the same time, Russian imports have collapsed by as much as 50%, not least because Moscow has been cut off by sanctions from machinery, semiconductors and other technology manufactured by the US and its allies. In May, automobile production was down 96% year-on-year, though it has recovered somewhat.

Meanwhile, Russia faces a drastic loss of human and financial capital, as skilled workers and high-net-worth individuals seize any available opportunity to get themselves and their money abroad. The scale of the drain of capital should not be exaggerated. According to Elina Ribakova of the Institute of International Finance, a significant number of foreign firms — notably from China, Italy, France and the Netherlands — continue to function in Russia. Nevertheless, it should be obvious that Russia’s economic outlook is bleak, particularly when it comes to equipping the Russian military with arms as sophisticated as those being supplied to Ukraine by the West.

Compared with the vast forces that fought on the territory of modern Ukraine during World War II, the armies doing battle today are small. However, they are armed with far more powerful and accurate weapons than were available to the armies of Hitler and Stalin.

Russia’s invasion force at the outset of the conflict numbered between 175,000 and 190,000, plus around 34,000 in separatist militias from the self-proclaimed Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics. Estimates of Russian casualties —killed and wounded — range widely. In August, the US and UK both put total Russian casualties at around 80,000. From this, Western analysts infer total deaths of 20,000 to 25,000. These figures include non-regular forces, such as the Donbas militias and mercenaries from the Wagner Group. The Russian casualty figures released by Ukraine are even higher. As of Sept. 1, Ukraine’s army reported killing over 48,000 Russian troops.

Western estimates imply a mortality rate of at least 9% to 12%. If Ukrainian claims are right, the figure is much higher: 25%-28%. These rates are staggeringly high by the standards of 20th- and 21st-century conflict. For example, US battle deaths in the Korean War amounted to 1.88% of the total force deployed there.

We know much less about Ukrainian military mortality. We should probably therefore assume that Ukrainian losses are on a similar scale to Russia’s.

Compare all these estimates to the death toll with the nine-year US war in Iraq, which saw 3,500 US soldiers killed in action and 32,000 wounded, or the US campaign in Afghanistan between 2001 and 2021, which cost the lives of over 2,000 American service personnel and left more than 20,000 wounded. In both cases, the fractions killed in action of total forces deployed were miniscule by the standards of today’s war in Ukraine.

Over 10 years, beginning at the end of 1979, the Soviet war in Afghanistan saw 15,000 Soviet soldiers killed and over 50,000 wounded. Russia may have suffered comparable casualties in just the first 10 weeks of this war.

On the other hand, today’s war appears to be less bloody than the Soviet-Finnish Winter War of 1939-40. During that three-month war, which resulted in a pyrrhic Soviet victory, the Soviet Union suffered over 300,000 casualties and Finland suffered 68,000. Yet the Soviet army was much larger than today’s Russian invasion force.

A better analogy may be the 18-month Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, in which estimates of Russian deaths ranged from 43,000 to 80,000 and Japanese deaths from 80,000 to 86,000. Putin will doubtless recall that Russia’s humiliating defeat in that war triggered a political revolution in Russia, though it failed to produce a lasting reform of the tsarist system.

Both sides urgently need to raise, arm and train additional forces. On Aug. 25, Putin ordered a 137,000-person increase in military personnel, raising the target number of active-duty service members to 1.15 million by January. Russia has also established new, highly paid “volunteer” battalions (400 men from each of Russia’s 85 regions). However, many of these new battalions and other units are undermanned. The Third Army Corps, now being sent to Ukraine, is one-third of its planned size. For reasons of domestic politics, Putin appears unwilling to risk proclaiming that this is a real war that necessitates general mobilization.

By contrast, Ukraine declared a general mobilization on Feb. 24 and currently has 700,000 troops across the military, national guard and territorial forces. Ukraine is no longer prioritizing fresh manpower, with Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov stating that the priority is now technical specialists rather than general recruits.

When it comes to weaponry, the Russians seem to remain well-supplied with artillery and other weapons. A report in the Washington Post last week provided evidence of the significant losses Russia has imposed on Ukraine’s Kherson counteroffensive.

But we know the Russians have lost a huge amount of armor and other equipment. The Ukrainians have done a good job of keeping the score in this regard.

We also know that the Russians have a dwindling supply of sophisticated weaponry. So effective are Western sanctions that they are reduced to acquiring drones from Iran as well as shells from North Korea. Meanwhile, Reznikov boasted on Saturday of the steady increase in the firepower being made available to Ukraine by the West.

At home, so far as Russian public opinion can be accurately assessed, the war is not so much popular as tolerated. In March, 75% of Russians said the “special military operation” was the most noteworthy event over the past month. By July, however, that number had fallen to 32%. On the whole, according to research by the Carnegie Endowment, the Russian public remains remarkably accepting of the official rationale for the army’s presence in Ukraine.

But the key issue is the morale of the Russian army. To repeat, wars end not when one side has killed more of the other side’s soldiers, but when one side’s soldiers lose the stomach to fight and begin to surrender, flee or desert. The events of the past 48 hours have given the first indication that at least some elements of the Russian invasion force have lost their stomach for this fight.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian morale could scarcely be higher. An August opinion survey found that 98% of Ukrainians believe their country will win the war. They are less willing today to give up on the idea of North Atlantic Treaty Organization membership than they were in April. Around 90% of Ukrainians either “strongly approve” or “somewhat approve” of Zelenskiy; 88% “strongly approve” of Ukraine’s military. Instead of weighing concessions, Ukraine’s leaders are openly discussing the liberation of Crimea to restore the pre-2014 borders, something 64% of Ukrainians believe is achievable by the end of the war.

Such expectations may ultimately be disappointed. Right now, however, they are a significant source of strength for the side defending its own territory against a despised invader or occupier, routinely referred to as “the orcs” by Ukrainian soldiers (an allusion to the goblins in J.R.R. Tolkien’s ubiquitous “Lord of the Rings).”

In March, Ukraine’s armed forces defied almost everyone’s expectations by winning the Battle of Kyiv. Six months later, they have again surprised the so-called realists with their eastern counteroffensive. However, to win this war, Ukraine cannot afford to lose economic stability. If the US and EU want to see a Ukrainian victory, they must step up their support immediately to reduce the Kyiv government’s budget deficit and help the central bank avoid runaway inflation.

Zelenskiy is right: The next three months will be crucial — though we should look even further ahead, beyond mid-December into January and February, usually the coldest months of the year in Ukraine. With the right military and financial assistance, Ukraine could celebrate the first anniversary of this war by driving Russia further back, if not all the way to the status quo ante of February 23, 2022. Without it, a winter of discontent will inevitably blow some of the stardust off the former entertainer turned war leader — and confront the Ukrainian people with the harsh reality that few struggles for national liberation have ever been won inside 12 months.

Between Lexington and Yorktown lay six long years.

Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

Patrick McGee: Tesla’s Robotaxi Bait and Switch

Elon Musk called self-driving cars a ‘solved problem’ 10 years ago. So how come he’s still working on it? In a new column, Patrick McGee…

Thought Leader: Patrick McGee

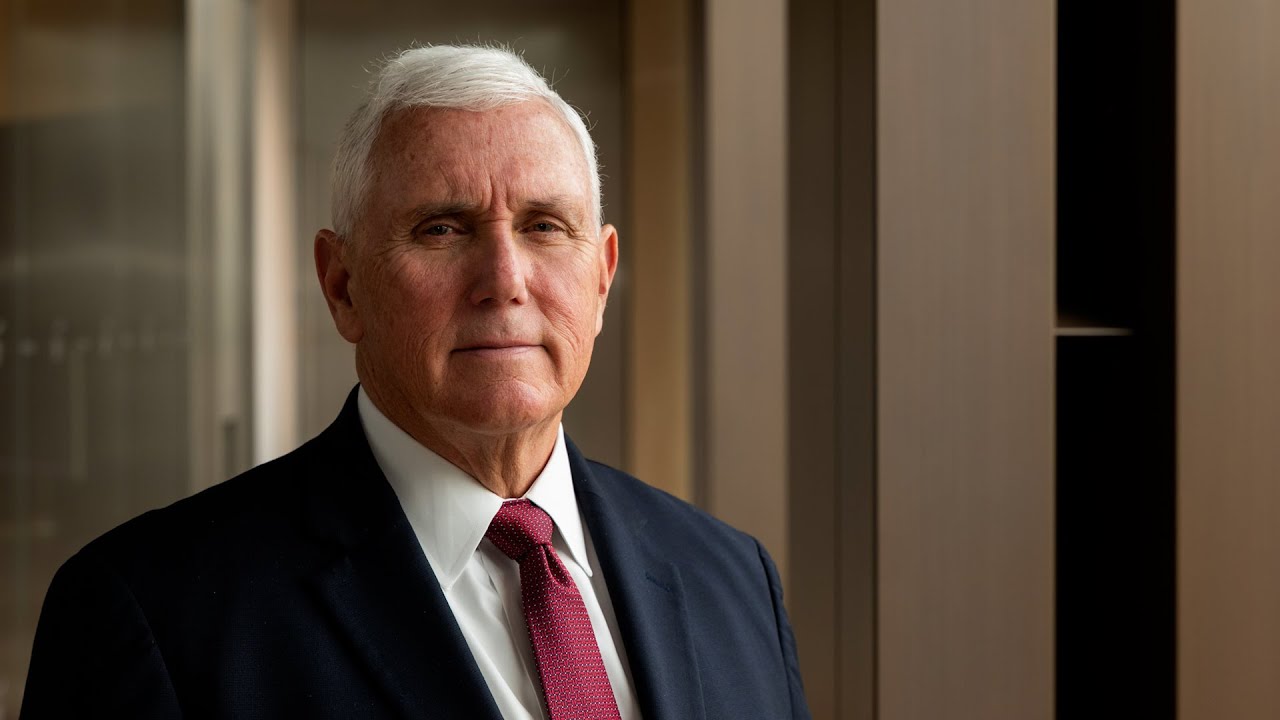

Mike Pence on U.S. Leadership and Global Strategy

Former Vice President of the United States, Mike Pence, shares his thoughts about President Trump’s framework on trying to acquire Greenland, and discusses what he…

Thought Leader: Mike Pence