Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

The Hon. Mark T. Esper,

US Secretary of Defense

In conversation with

Frederick Kempe,

President & CEO,

Atlantic Council

FREDERICK KEMPE: Hello and welcome to this edition of Atlantic Council Front Page, or #ACFrontPage, our premier live ideas forum for global leaders. Today we have the honor of hosting US Secretary of Defense Mark T. Esper for a discussion about the role allies and partners play in US national security—a question that has been the Atlantic Council’s work since its founding in 1961. Secretary Esper, we know how busy you are and the challenges you confront ever day across the world. And indeed, next week you will leave on another trip to attend the 2+2 meeting with Secretary Pompeo in India. So thanks so—thank you so much for taking the time to join us.

Secretary Esper serves as the 27th US secretary of defense, having been confirmed by the United States Senate in July of 2019 with a vote of ninety to eight. Prior to assuming his current position, he was the 23rd US secretary of the Army from 2017 to 2019. Secretary Esper spent ten years on active duty in the Army, serving as an infantry officer with the 101st Airborne, also known as the Screaming Eagles. And he served with them during Desert Storm and the Gulf War, where he was awarded the Bronze Star and various other medals. He’s a graduate in engineering from West Point, where he received the Douglas MacArthur Award for Leadership. He has a master’s degree from the Kennedy School at Harvard, and a doctorate in public policy from George Washington University. He has also had a number of increasingly responsible positions in the Senate and served as deputy assistant secretary of defense in the Pentagon as well. So that’s just a remarkable track record of public service.

This session is being hosted by our Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, directed by a former Pentagon official himself, former White House official Barry Pavel. The Center honors the legacy of General Brent Scowcroft, the only man to have been appointed by two presidents to serve twice as national security advisor. He passed away this August at the age of ninety-five. For the United States, for the world, and for us—for all of us at the Atlantic Council, it was still too early.

It’s fitting, Secretary Esper, that today we will be talking about the significance of allies in our new era of great-power competition because nothing animated General Scowcroft more in his support of the Atlantic Council than allied relations, except, perhaps, the mentoring of future generations.

The Scowcroft Center just last week published twenty bold ideas for NATO in 2020, a compendium of twenty innovative ideas ranging from a focus on the Arctic to how NATO might partner with allies in the Indo-Pacific to questions in expanding membership.

The Scowcroft Center also recently published a foundational, quote, “primer on hypersonic weapons in the Indo-Pacific region,” unquote, which considers the potential contributions of existing US allies like Japan and Australia, along with additional potential partners like Singapore and India in this growing category of strategic weapons, and I know there’s been much thought and action in the Pentagon regarding all of this.

So, Mr. Secretary, as these works demonstrate, reinvigorating US alliances and exploring new partnerships is core to the national security work that we’ve always done here, and more now than ever. We are delighted our work has been in alignment with the 2018 National Defense Strategy, which calls for working even more closely with allies and partners to secure our common future.

Secretary Esper, we are eager to hear your insights and analysis in this key dimension of US national security and how you and the Department of Defense are tackling cooperation efforts. We’re on the record. We are streaming on multiple platforms around the world. If any in our global audience would like to tweet, please do so using ACFrontPage—#ACFrontPage.

Mr. Secretary, the floor is yours for opening comments, which will follow with a set of questions. Thank you.

MARK T. ESPER: Well, good afternoon, and thank you, Fred, for that kind introduction. It’s great to see you again. And thank you also for the quick remembrance of General Brent Scowcroft. He was a great man, an outstanding leader, and he is missed by all. He taught us all a great deal. So thank you for that too.

It’s a pleasure to be here with all of you, and I want to thank the Atlantic Council for hosting today’s discussion. For decades, your expertise has been vital to strengthening transatlantic ties, and will be even more critical in the years ahead as we face an increasingly complex security environment.

Since my confirmation as Secretary of Defense well over a year ago, my number one priority has been implementing the National Defense Strategy. The NDS tells us that we are now in an era of great power competition, with our primary competitors being China and Russia. At the same time, we face ongoing threats from rogue states such as North Korea and Iran. And finally, regrettably, we will be dealing with Violent Extremist Organizations for years to come.

As we prepare the Department for these challenges, the NDS guides us along three lines of effort: first, improving the lethality and readiness of the force; second, strengthening alliances and building partnerships; and third, reforming the Department to redirect our time, money, and manpower to our highest priorities. I also added a fourth, personal priority: taking care of our Service members and their families.

To drive lasting change across an enterprise as large and complex as the Defense Department, we distilled these three lines of effort into ten targeted goals. These include tasks from focusing the Department on China, updating our key war plans, and modernizing the force by investing in game-changing technologies, to reforming the Fourth Estate, achieving a higher level of readiness, and implementing enhanced operational concepts such as Dynamic Force Employment. It also includes establishing realistic joint war games, exercises, and training plans, and developing a modern joint warfighting concept that will ultimately become doctrine.

I’m proud to report that we’ve made solid gains across the board. In recent weeks, I’ve detailed our progress in improving readiness across all three services and building a more lethal force, namely a future Navy of more than 500 manned and unmanned ships called Battle Force 2045. Today, I’d like to focus on another top 10 goal: developing a coordinated strategic approach to strengthen alliances and build partnerships.

Forged through the fires of combat and shared sacrifice, America’s network of allies and partners provides us an asymmetric advantage our adversaries cannot match. Rooted deep in our common values and interests, many of these relationships have weathered the storms of history and remain the backbone of the international rules-based order.

Most people are familiar with the critical role that America’s oldest ally – France – played in our Nation’s founding. But lesser known is the fact that 1,800 Knights and volunteers from Malta enlisted in the French Navy to aid Americans in the cause for freedom. Together, they played a decisive role in the Battle of the Chesapeake, cutting off maritime support to British forces at Yorktown, and ultimately forcing their surrender.

Only a few decades later, Malta stepped up again, providing a key port for American ships in the fight against the Barbary pirates.

And in the 20th century, the United States answered the call after Axis powers waged a relentless bombing campaign against Malta during World War II. Through resupply operations, Allied nations broke the Axis siege, rescuing the people of Malta and establishing a launch pad for victory in North Africa.

Today, our two nations remain steadfast partners, and several weeks ago, I visited Malta to see our cooperation in action at the crossroads of the Mediterranean, and discuss the challenges we jointly face in North Africa. Examples like these illustrate the importance of aligning with like-minded nations – large and small – to maintain the free and open order that has served us all so very well for decades.

Today, our global constellation of allies and partners remain an enduring strength that our competitors and adversaries simply cannot match. In fact, China and Russia probably have fewer than ten allies combined. However, our ability to maintain this advantage is not preordained, nor can we take our longstanding network of relationships for granted.

On one hand, our primary competitors – China and Russia – are rapidly modernizing their armed forces, and using their growing strength to ignore international law, violate the sovereignty of smaller states, and shift the balance of power in their favor.

China’s militarization of land features in the South China Sea and Russia’s attempted annexation of Crimea and incursion into eastern Ukraine demonstrate their brazen attempts to chip away at the autonomy of others and undermine the resilience and cohesion of countries and institutions critical to U.S. security, including NATO.

On the other hand, Beijing and Moscow are also using broader yet more subtle means to exert economic leverage over such nations and institutions and coerce them into suboptimal security decisions.

Through its One Belt – One Road Initiative, the PRC is expanding its financial ties across Asia, Europe, Africa, and the Americas, with the ulterior motive of gaining strategic influence, access to key resources, and military footholds around the world.

In fact, the smaller the nation and the greater its needs, the heavier the pressure from Beijing.

For example, Belt and Road Investments have created unhealthy economic dependencies in Burma, and they have pushed Laos into an unsustainable debt burden. In Cambodia, China has received generous land entitlements to construct ports, airfields, and associated infrastructure that could be used for military purposes to extend Beijing’s strategic reach.

Helping other nations resist aggressive military posturing, financial entrapments, and other forms of coercion will require us to break from business as usual.

It will require us to align the Department’s efforts and resources for maximum impact and influence.

And it will require us to think and act more strategically and competitively.

Today, I’d like to share with you two recent initiatives that will help us do just that: the first being the brand new Department of Defense Guidance for Development of Alliances and Partnerships – we call it the GDAP – and the second being Defense Trade Modernization.

Together, these efforts will help us build the capacity and capabilities of like-minded nations and foster interoperability with friendly militaries, while promoting a stronger domestic industrial base that can compete in the global marketplace.

First, to meet the demands of 21st century great power competition, I directed the Pentagon’s Office of Policy to develop a first-of-its-kind, comprehensive strategic approach to strengthening alliances and building partnerships.

And earlier this month, I’m proud to report that we officially set this into motion when I signed out the GDAP, which will drive this new strategy for how we engage with allies and partners around the globe.

In the past, our international engagements were guided by regional priorities and interests. But we are now in an era of great power competition that is global in nature. This reality requires a common set of priorities across the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Joint Staff, the Services, and the Combatant Commands, that will drive our interactions with our foreign counterparts and improve our effectiveness.

More specifically, the GDAP will enable us to: prioritize, align, and synchronize our security cooperation activities across Title 10 authorities to build partner capacity; better articulate the Department’s needs for priority ally and partner warfighting roles through future force planning; focus our efforts to help them shape their militaries into more capable forces; and measure and track our progress across a wide range of tools available to the Defense Department.

For example, I have focused the Department’s management team on four important elements of the Department’s competitive tool kit: key leader engagement, International Professional Military Education, the State Partnership Program, and Foreign Military Sales.

First, under key leader engagement, we are developing detailed ways to prioritize engagements, establish a common set of objectives, and chart our progress with each country. In any given week, scores of senior leaders from across the Department are engaging with their counterparts around the world. Over the past year, I have personally conducted over 200 meetings with foreign partners from over 60 countries across the globe. In the last month alone, I traveled to six countries in North Africa and the Middle East; met with Defense Ministers of eight countries from Europe and Asia; and conducted calls with another six, as well as NATO Secretary General Stoltenberg.

Previously, we did not have a central repository for tracking senior leader engagements across the enterprise, let alone directing them, and then measuring progress against our collective goals. It is very difficult to improve a process – let alone a relationship – if you don’t have a goal, and you don’t measure it. Nor can you make a resource like key leader engagements more effective in strategic competition if you don’t monitor and assess it. So we are now tracking and analyzing these engagements across the enterprise. This tool will also give senior leaders enhanced awareness on areas to engage and advocate for participation in exercises, for key Foreign Military Sales, and for other means to help build the capability and capacity of ally and partner militaries.

Here’s how we’re putting this into action. In preparation for the upcoming NATO Defense Ministerial, I recently held bilateral meetings with our allies Romania and Bulgaria to further expand our defense cooperation, to discuss ways to optimize our force posture on the continent, and enhance the deterrence of Russia in the Black Sea region.

These types of targeted key leader engagements will be essential as we implement the reform plan we announced this summer to reposition our forces in Europe to better align with great power competition. In consultation with our allies, we will continue to refine and enhance our moves in line with our five key principles: Number one, enhance deterrence of Russia. Number two, strengthen NATO. Number three, reassure allies. Number four, improve U.S. strategic flexibility and European Command operational flexibility. And number five, take care of our Service members and their families in the process.

Indeed, since that announcement, as well as the signing of the Defense Cooperation Agreement with Poland, my recent meetings with the Defense Ministers from Romania and Bulgaria, and correspondence received from Baltic States, there is now the real opportunity of keeping the 2nd Cavalry Regiment forward in some of these countries on an enduring basis.

Moreover, when I address the entire Alliance later this week, I will continue to push for improving readiness, increasing burden sharing, and solving common challenges in light of my recent bilateral discussions.

We have made solid progress in several areas these past few years. When it comes to burden sharing, for example, from 2016 to now our NATO allies have added a total of $130 billion to defense spending thanks to the United States’ leadership. Even better, we expect that figure to top $400 billion by 2024.

As of June, nine Allies were meeting the two percent of GDP defense spending commitment. That is up from five in 2016.

And while we recognize the challenges and costs posed by the COVID pandemic, our threats today have not diminished. Rather, they have only been exacerbated as nations turn inward to recover, and our competitors seek to exploit the global crisis.

That is why we urge all member states to uphold their commitments and contribute more to our collective security. This goes beyond NATO as well. We expect all allies to invest more in defense – at least two percent of GDP as the floor. We also expect them to be ready, capable, and willing to deploy when trouble calls. And we expect them to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the United States in confronting Chinese bad behavior and Russian aggression. To overcome the increasingly-complex threats in the 21st century and defend our shared values, there can be no free riders to our common security.

A second tool we use to operationalize the GDAP is International Professional Military Education. One of our best means for strengthening existing partnerships and cultivating new ones is education and training programs, especially those run right here at home.

The United States provides allies and partners with access to almost 400 U.S.-led Professional Military Education courses for the next generation of foreign leaders to learn alongside our best and brightest.

I have personally benefited from these sorts of programs, from attending West Point with students from other countries, to training at the Hellenic Military Academy in Greece as a cadet, and studying with an officer from Africa during the Army’s Infantry Officer Basic Course in 1986.

Programs like these promote closer relationships with valuable partners around the world while also introducing them to our training, equipment, values, and way of life. That is why I have asked the Department to find ways to expand the programs with the highest potential for enduring impact, increasing their student participation by 10 percent in fiscal year 2021, and over 50 percent between fiscal year 2021 and 2025. At the same time, we need Congressional support for expanded Defense Department authority to conduct these programs if we are to truly maximize their impact over the long run.

Third, we are exploring ways to optimize and expand the State Partnership Program. Established in 1993 by the National Guard Bureau, this program was designed to build relationships with former Soviet Bloc nations. Starting with just three partnerships in the Baltics, today it boasts 82 around the world – and each U.S. state, territory, and the District of Columbia has at least one partner.

The program continues to grow and expand with four relationships pending. I’d like to add eight on top of that by the end of 2025. To support this we are looking at increasing funding and making those resources more consistent and predictable – but we need Congressional support to do so.

At the same time, the program must also shift its focus to frontline and emerging partner nations to compete with China and Russia. We will undertake an independent strategic evaluation to look at all existing partnerships to help us find efficiencies and increase the effectiveness of this important program.

Finally, under Foreign Military Sales, we are focused on the need to better utilize our premier equipment, technology, and systems as a strategic tool to improve ally and partner warfighting capabilities, while building interoperability with our Armed Forces and deepening the relationship between our countries.

In fiscal year 2019, we maintained sales of more than $55 billion for the second consecutive year, which increased our three-year rolling average for sales by 16 percent.

In the Indo-Pacific alone, there are currently worth – more than $160 billion worth of projects under way, including $22 billion in newly initiated projects in this fiscal year alone – which is almost half of all Foreign Military Sales globally. We are providing F-35 aircraft to Japan, Seahawk and Apache helicopters to India, and F-16 fighter jets to Taiwan, to name a few examples.

And as a supplementary tool to counter Chinese aggression, we are also delivering excess defense articles to partners in the region. For instance, we are providing Vietnam an additional high-endurance coast guard cutter for enhanced maritime security in the South China Sea.

The strength of Foreign Military Sales as a tool for advancing our relationships is equal to its potential for unleashing our domestic industrial base for innovation at home and strategic competition in the global marketplace.

So in line with the GDAP, we launched a complementary, parallel effort to further prepare the Department for Great Power Competition: Defense Trade Modernization.

This initiative seeks to solve two core problems. First, I continue to hear from foreign Defense Ministers and U.S. industry that our defense export processes are often too slow, opaque, and complicated.

Second, we must compete with China and Russia, whose state-owned industries can fast track military exports in ways that we cannot – and would never want to in many cases. As Beijing and Moscow work to expand their share of the world’s weapons market, they attract other countries into their security networks, challenge the United States’ efforts to cultivate relationships, and complicate the future operating environment at the same time.

In light of these challenges, we set out to reform our approach to make the United States more competitive in the global marketplace and to strengthen our cooperation with allies and partners. Going forward, and in closer collaboration with industry, the Department will take a more strategic, enterprise approach to Foreign Military Sales and security cooperation.

That is why, last month, I directed several changes to our defense export systems across four key areas: Number one, require early exportability for critical weapon systems. Two, institute an agile framework for technology release. Three, prioritize countries or capabilities – or both – to capture or keep key markets. And four, improve the predictability of international demand to inform commercial investments and increase industrial capacity

As part of these efforts, we are developing a Foreign Military Sales dashboard, informed by the GDAP, that will track the most important cases moving along the process to ensure our partners get the equipment and systems they need, when they need them. Moreover, it will prioritize cases that enhance lethality and interoperability with the U.S., enable the domestic industrial base, and deny market space to China and Russia.

Another example of Defense Trade Modernization in action was our work with the White House and interagency to modernize the regulations governing exports of unmanned aerial systems. Decades old rules handicapped our industrial base – and by extension, our partners – by unnecessarily limiting UAS sales. Through the President’s actions this summer, we will bolster our economic security at home, while improving the capabilities of our partners abroad.

In the months and years to come, these efforts will provide a cohesive, coordinated, and measurable approach for how we invest in, enhance, and assess our defense cooperation worldwide.

Great power competition requires us to engage with every nation more strategically, no matter its size. We cannot overlook countries like Malta – as history has shown.

As an example of our new way of thinking, earlier this summer, I became the first Secretary of Defense to visit Palau – a small island country, but critical to power-projection in the Western Pacific. A year before that, I visited Mongolia, another important country in a geo-strategic location.

At the other end of the spectrum, we need to strengthen ties with large like-minded democracies, such as India and Indonesia.

Last week, I hosted the Indonesian Defense Minister at the Pentagon to discuss issues ranging from joint training and arms sales, to personnel exchanges, human rights, and regional political affairs.

Next week, I’ll travel to New Delhi for the third 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue between our countries. Established in 2018, these meetings reflect our nations’ ever-increasing convergence on the strategic issues of our time.

Last year, we conducted our first-ever tri-service military exercise – TIGER TRIUMPH – with India. And in July, the USS Nimitz conducted a combined exercise with the Indian Navy as it transited the Indian Ocean. We also held our first ever U.S.-India defense cyber dialogue in September, as we expand our collaboration into new domains. Together, these efforts will strengthen what may become one of the most consequential partnerships of the 21st century.

As we continue to bolster strategic relationships with like-minded nations, we are also deepening cooperation with our most loyal partners. Shortly after the signing of the historic, U.S.-facilitated Abraham Accords, I hosted my Israeli counterpart at the Pentagon to reaffirm the United States’ commitment to Israel’s qualitative military edge. And I hope to visit Tel Aviv in the coming weeks to follow up on our discussions.

We continue to work closely to develop advanced capabilities, particularly in missile defense. In August, our two nations completed a successful test of the Arrow 2 air defense system by intercepting a Medium Range Ballistic Missile target. And in September, the U.S. Army took delivery of its first IRON DOME missile defense system, increasing our capability to defend against a wide range of airborne threats.

Meanwhile, the signing of the Abraham Accords by the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain reflect their leadership in the Middle East. To address Iranian aggression in the region, both nations helped form the International Maritime Security Construct, and Bahrain now hosts its headquarters at Naval Forces Central Command in Manama. The IMSC is also collocated with the Combined Maritime Forces headquarters – a 33-nation partnership to counter illicit non-state actors and advance freedom of navigation in the region.

These are the types of targeted engagements and cooperation we hope to expand in the months and years ahead. As we look to the future, the groundbreaking initiatives I have laid out today will only further complement our wide range of objectives that implement the National Defense Strategy.

For instance, this April, I signed the Joint Operational Training Infrastructure Strategy to integrate our efforts to modernize operational training over the next ten years – and fulfill another top 10 goal. The next step in ensuring Joint Force training replicates a high-end fight against our competitors requires incorporating our allies and partners.

We’re already moving in this direction as we implement enhanced operational concepts such as Dynamic Force Employment – also a top 10 NDS goal. Earlier this year, as part of the new Bomber Task Force missions, a B-1 bomber flew from the continental United States and integrated with Japanese fighters for joint training near Japan. And in August, six B-52 bombers from Minot Air Force Base overflew all 30 NATO countries in a single day, integrating with allied fighter aircraft along the way. This robust show of force by a broad coalition did not go unnoticed by Moscow. Neither did our ability to rapidly deploy our bombers anywhere, at any time, sending a strong message of our commitment to allies and partners.

Furthermore, as we move through our Combatant Command reviews and optimize force posture in various theaters, we are considering additional deployments of the Army’s Security Force Assistance Brigade. Earlier this year, I directed elements of the Army’s 1st SFAB to Africa to conduct train, advise, and assist missions, while we return elements of the 101st Airborne Division back home to prepare for high-intensity conflict. Elements of other SFABs are currently in CENTCOM and SOUTHCOM. These are just the first of many decisions we will make as we complete the Combatant Command reviews and pursue innovative means to strengthen our defense cooperation worldwide, while better preparing for the high-end fight.

In closing, the United States is – and will remain – the global security partner of choice, not only because of the actions I laid out today, but more importantly, because of our capabilities, our commitments, and our values.

Unlike other competitors, we respect the sovereignty of all nations, large and small; we uphold international rules and norms; we believe in the peaceful resolution of disputes; and we promote free, fair, and reciprocal trade.

And thanks to the efforts described earlier, we will implement the National Defense Strategy and build a more ready, capable, stronger, and better connected constellation of allies and partners that is so very important to our national security. Together, we will continue to deter conflict, preserve peace, and defend the free and open order that has served us all so well, for many more generations to come.

Thank you.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Mr. Secretary, if we had a full house right now I think you’d be hearing quite an ovation. That was a remarkable speech, a lot of new detail in it, at least for many of our audience, and a lot of smart people in our audience. There was a lot of new detail.

I have one sort of overarching question that the whole speech sort of speaks to, and that is it seems to be a resounding underscoring of the strategic necessity of allies, maybe even more now in a new era of global competition, or at least in a different way. Could you just speak to that overall question of is the strategic necessity of allies even greater now?

MARK T. ESPER: I think in many ways you’re correct, it is great. It’s not because we have to deter and be prepared for a conflict against a resurgent Russia, something that, you know, twenty-five or so years ago when I was serving in Europe, in the early 1990s, we were celebrating the end of the Cold War and we were celebrating the dismantlement of the Soviet Union. And here we find ourselves back again dealing with a revanchist Russia, something I don’t think any of us anticipated. At the same time, we know that for the past two to three decades China has been slowly, carefully, quietly building up its military capabilities, building its economy, and also acting in ways that challenge the international rules-based order.

So allies become now more important than ever. It’s not just the allies in the—in the European theater; it’s the allies in the Indo-Pacific theater. And because this is great-power competition, it’s global in nature. So we see Russia and China on the move in the Americas, in Africa, in the Middle East, in the Arctic, in the Antarctic. So we have to compete and we have to compete aggressively—all of us, together. And again, if deterrence fails, we need to be prepared for the worst.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thank you, Mr. Secretary.

Just to our global audience of viewers and listeners, in the beginning there were a couple of glitches of sound. We’ve heard about that. In the final version that we will post, all that audio will be cleaned up. You’ll definitely have a transcript of the secretary’s very important remarks, and, as I understand, most of this has been well received. And so I just wanted to say that for those that have missed any part of this really important statement.

I mentioned—and you were kind enough to salute General Scowcroft. He embodied the Atlantic Council’s devotion to developing strategies when working with allies—to develop strategies and work with allies. We’ve been doubling down on that legacy at the Atlantic Council.

How do you prioritize development of joint strategies with allies and partners, which, you know, you talked about jointness within the US. But how do you do jointness with allies through this period of time?

And you also talked in the two areas—major areas that you’re outlining and I always—I always love a new Pentagon acronym, GDAP.

MARK T. ESPER: GDAP.

FREDERICK KEMPE: (Laughter.) And perhaps you can also talk about whether there’s an area where we could expand defense industrial cooperation with allies, so not just MFS but also working strongly with allies to improve our capabilities.

MARK T. ESPER: Well, we, certainly, need to integrate our allies into all of our planning and preparation. It’s not just the right thing to do, it’s necessary. It’s even called for in the National Defense Strategy. You know, so as I sat down with my leadership team, both uniform and military, fifteen months or so ago now and we looked at the National Defense Strategy and we figured out how do we move forward with this goal of irreversible implementation of NDS, one of the things that came out was that we did not have a coherent strategic approach to allies and partners.

That was the genesis of the GDAP, the global plan to develop allies and partners. And so what you found at times, for example, anecdotally, you’d go to a—you’d hear from a foreign country, a partner, an ally, who would say, look, I’m not clear what you want me to do because this secretary came in and said, we want you to buy this, a combatant commander came in and said, buy that, and an undersecretary said, buy this. Same thing is true with exercises.

So what we wanted to do was, really, look at all those key levers that I mentioned in my remarks—foreign military sales, training and exercises, key leader engagements, purchases, et cetera—and make sure that they were centralized and focused, and focused on what’s important to the—to us and to them in terms of the department’s approach, rather than having a regional approach or a disaggregated approach that was, in some ways, lending toward confusion and not necessarily maximizing the power of and the synergy of bringing it all together.

So that is really the fundamental purpose of this document, the GDAP. And so now if you go into there you can look at any of the few dozen countries we have in there and it’ll be—it’ll be a very clear, detailed approach of how we will engage allies and partners, and work to build this—to build and strengthen this network of alliances and partnerships, because we do need everybody engaged. We do need everybody to invest and build that capability and capacity that will be necessary to deter conflict and protect this rules-based order that’s served us so well since the end of World War II.

FREDERICK KEMPE: And is it, at the same time, a recognition that we aren’t where we ought to be in that area and, therefore, you’re introducing these new measures, or we would have had to do this anyway because the landscape is changing?

MARK T. ESPER: Probably both, but we need to accelerate. So I gave the stats in my remarks about in 2016 we had five countries in NATO meeting the 2 percent threshold, despite the Wales Pledge, and now we have nine. We have—you know, we have two dozen more to go. Twenty-nine or thirty countries now in NATO.

So we have a lot more work to do. We need countries to contribute more, not because it’s some arbitrary threshold. I think it’s a solid floor upon which to build upon. Because if you had the capability, again, we will deter conflict and we won’t have to worry about the things that we concern ourselves about right now.

FREDERICK KEMPE: So I’m going to be asking some questions of my own and some that are an amalgam of my questions, and then some that have been volunteered to us from some in our audience. This was a speech focusing on allies.

Let’s go into capabilities a bit. During the very famous Kennedy-Nixon campaign that came shortly before the birth of the Atlantic Council, the whole controversy about a missile gap emerged. Do we and our allies now face the danger of a capabilities gap? You know about the book that’s come out, “Kill Chain,” that focuses on this. Are our adversaries either getting ahead of us or in danger of getting ahead of us in developing disruptive next-generation capabilities while we continue to focus on legacy systems? A couple you can point at. You can talk to hypersonic. You can look at space. You can look at cyber.

And so the first question is, is one developing? And second of all, how do allies fit into this picture?

MARK T. ESPER: Yeah. Well, first let me say I am fully confident that we would prevail in any conflict today, hands down, no doubt whatsoever. So I say that first.

Second I’d say is there are areas where we need to invest more and do more. And I’m also equally confident that we are doing that right now in terms of the funding we are putting into things such as hypersonics, directed energy, artificial intelligence, you name it. We are putting billions of dollars into these types of assistance, because you look at what the Chinese are doing, for example. Between the year 2000 and 2016, I think they invested—they had 10 percent annual real growth in their defense budget. And in these past few years, it’s been 5 to 7 percent, so significant increases in their defense budget. And Russia is investing as well.

So we need to keep apace. I’ve argued that we should have, based on what we assess and what the National Defense Strategy Commission has recommended, 3 to 5 percent annual real growth each year. And then we can look at areas to point—to look at. You mentioned the missile gap. At the time when that happened, that was about intercontinental ballistic missiles. But we see, as a result of a Chinese buildup in the—

FREDERICK KEMPE: And to remind viewers, you know, Kennedy was saying there was one that he thought was enormously large. And then when he became president, he actually found out that wasn’t the case.

MARK T. ESPER: Yeah. And remember, it was followed by the bomber cap—gap too.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Yeah.

MARK T. ESPER: Or the bomber gap preceded it. But the Chinese have built an extensive array of well over a thousand missiles, intermediate-range ballistic missiles, in the Pacific. And the Russians have too. And they did it in violation of the INF Treaty. And we recognize this in NATO. We did last year. So we are committed to making sure that we build similar capabilities for both theaters. But at the same time, we need to improve our missile defenses against those type of systems and others.

There are other areas that we don’t talk about enough too. Look, both China and Russia have taken the peaceful domain of space and militarized it. They’ve put weapons in space. And if we’re going to protect and safeguard the heavens, if you will, the place from which we not just advance our security but we facilitate commercial transactions, we look at the weather, we understand what’s happening on our planet, if we’re going to protect that, we’re going to need to build defensive systems to compete in space.

Cyber is the same thing, another area where we have to do it. And then, as I mentioned, I’ve recently rolled out Battle Force 2045. We have to compete on the high seas. We have to have a Navy that has forward presence, that can control sea lanes, that can ensure freedom of navigation and commerce. And we will need a much bigger, more capable Navy to do that.

So there are areas where we need to work. But the allies have a role. This morning—I told you before we came in—I spoke to my counterpart in the UK, Defense Minister Ben Wallace. And he and I had a very good conversation. But they’re putting the Queen Elizabeth to sea, their carrier. And she has plans to sail to the Pacific next year with, by the way, US Marine Corps F-35s on board, joint training, real time, day by day, week by week. But she will be in the Indo-Pacific to do that next year. So it’s just a good example. And we have other European allies and traditional allies from that region there all the time, cooperating and working together.

FREDERICK KEMPE: So thank you, Mr. Secretary. Let’s jump—we’ve got a little short of twenty minutes left. Let’s jump to a couple of regions around the world. As you mentioned in your speech and I mentioned in my opening, you’re off to 2+2 meetings in India. There’s been some interesting news; Australia—the announcement today that Australia is going to join naval drills involving India, US, and Japan. That’s an interesting development. Word is that there’ll be a maritime information-sharing agreement signed in India.

Can you tell me—and also a piece of news that a Chinese soldier wandered across the border in India and was taken by the Indians. I don’t expect you to comment on that. But there’s things going on. So give us a little bit of an insight into the significance of the potential maritime agreement and the trip itself and the 2+2.

MARK T. ESPER: Well, you’re correct. Secretary Pompeo and I will be there next week. It’s our second 2+2 with the Indians, the third ever for the United States and India. And it’s very important. India will well be the most consequential partner for us, I think, in the Indo-Pacific for sure, in this century.

And look, it’s the world’s largest democracy—a very capable country, a very talented people. And they face off every day Chinese aggression in the Himalayas, specifically along that line of actual control. So like so many other countries in that region—and I’ve spoken with them, I’ve traveled from—like I said, from Mongolia all the way down south to New Zealand and Australia, from as far as Thailand to Palau and the Pacific Island countries.

They all recognize what China is doing. In some cases it’s very overt. And in many more cases, it’s very opaque what they’re doing. But they are putting political pressure, diplomatic pressure, and in some cases like India military pressure on countries to bend to their way. And we just can’t put up with that. We need to—we need all countries to follow the international rules-based order, to follow the norms that have served us so well. It’s not an issue about China’s rise, it’s how they rise. And that’s what we talk about in all these forums.

Last week we had a Five Eyes forum, right, the US, New Zealand, UK, Canada, and UK—I’m forgetting one, maybe us. Anyways, we had the Five Eyes forum and we talked about the challenges in the Indo-Pacific, and how do we—how do we cooperate together? How do we confront these challenges to sovereignty, to the international rules-based order, to freedom of navigation? So you see a lot more closer collaboration come out. And this’ll be reflected in our meetings next week in New Delhi, as well, when we travel there.

FREDERICK KEMPE: And this maritime information sharing agreement is part of that, then?

MARK T. ESPER: We have a number of things we’ve been discussing with the Indians for some time. We’ve made good progress on a number of them. But we’ll release information on that when it’s appropriate.

FREDERICK KEMPE: That sounds great.

You spoke quite a bit about I guess what’s now being called the quad, and the importance of it as sort of a breakthrough. For a long time, people who have seen the effectiveness of NATO over the years have despaired that we’ve never had anything quite like that in the region. Does this start going in that direction? And what do you see as the significance of this coming together?

MARK T. ESPER: Well, the important thing is you get, you know, four very important, very capable democracies—the United States, Japan, Australia, India—talking and discussing the challenges they face in the region. And these are mutual challenges. We have common concerns. We have shared values that we—that are being aggressed against. So I think it’s a very good development that we’re doing this, and that we would be exercising together.

It’s all a trajectory that we are—or, a journey, if you will—that we’re moving upon. But I think we need to continue to build those ties. Again, it is about protecting our values. It’s about building partnerships and strengthening allies. That’s why I’ve spent so much time on the road this past fifteen to sixteen months—on the road, on the phone, in meetings, trying to build these allies, these partnerships so that we can—we can, again, defend what has served us so well for decades now,

FREDERICK KEMPE: I loved the reference in your speech to Malta. And I wonder how the US can work better with smaller countries in the Indo-Pacific. Perhaps Papua New Guinea, Timor-Leste, to generate disproportionately beneficial effects, which I think was what you were speaking of regarding Malta.

MARK T. ESPER: Yeah, these countries are all important. They’re all strategically located. We have activities going on with our friends in Timor-Leste and Papua New Guinea. For example, I hope to get there sometime in the coming year. And I mentioned my trip to Palau, first secretary of defense ever. But we’ve had a continuous military presence there since 1969. Most people wouldn’t know that. And when I was there, we talked—we looked at our civic action teams, who are there doing a combination of work for the community and work for us.

And in fact, we also had the Seabees there, who were scraping out an airfield on the island. It was an airfield used, ironically, in World War II to fight against the imperial Japan. But they were carving it out, cleaning it up, so that the Army could land and bring in troops as part of an exercise called Defender Pacific. And also while I was there I had the chance to see some Marines who were there on an expeditionary fast transport ship. So you can see a big military presence. They are great people. And they really like our presence. And it’s important, again, to help those countries out, and to also make sure they know we’re there to defend them as well, as we look ahead to the future.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thank you for that, Mr. Secretary.

So let’s move to Europe and, to a certain extent, staying in the Indo-Pacific, or wherever else in the world. You know, Secretary General of NATO Stoltenberg spoke at the Atlantic Council not too long about his reflection of NATO 2030, looking at a more political and more global NATO. What opportunities do you perceive in that? I think partly he’s saying a lot of these challenges are not purely—in fact, few of them are purely military in nature. Is there an opportunity for more NATO allies to be involved in US strategy to counter China and Russia in the Indo-Pacific?

MARK T. ESPER: Oh, yes. Absolutely. Look, first of all, Jens Stoltenberg is a great NATO secretary general. I spoke with him yesterday for quite some time as we prepare for this week’s defense ministerial meeting. He’s done a great job because he has looked at the alliance not just through a military lens, but through the broader political lens. And has really led us to thinking more broadly about the threats of China. So for example, we’ve had numerous discussions over the past fifteen to sixteen months about how do we keep the PRC, specifically Huawei, out of our networks?

Now, why is that important? Because they are selling a product out there, they are trying to grab market share, and what it threatens is the alliance by jeopardizing our telecommunications links, our ability to share information, our ability to coordinate war plans. So we’ve been really successful in terms of looking at China holistically and bringing many countries on board to reject this type of offer by Huawei. You saw the UK come aboard just a few months ago. Other countries have as well. China is working its way throughout Europe as well. And so people are becoming much more aware of that presence.

And of course, Russia has a presence and is aiming to expand it in the Pacific too. And then there’s the common ground of the Arctic, right, where we see Arctic countries like the United States, and Canada, and others—and we actually have Russia and China there as well. So a number of areas where countries need to get together and make sure we have a coordinated strategy to deal with these—with these challenges.

FREDERICK KEMPE: A lot on the plate. Two related questions on Europe. You know, how is the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement with Poland going? How has it strengthened things? Is there a model there for other NATO countries? And then I’ll pivot from that to basically force posture reductions in Europe elsewhere, and how do you use security cooperation, interoperability to deal with this? Are there opportunities for NATO allies to fill in these gaps? How are you handling that? So what does Poland bring us, and then is there any danger in force power reductions? And what are the plans to compensate for that?

MARK T. ESPER: Sure. I’m going to answer your questions in reverse order.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Great. Great.

MARK T. ESPER: So we’re looking at reductions in Germany, not Europe. And we’re looking to reposition in Europe. Why is that? Because, again, we know the challenges faced by our allies, vis-à-vis Russia. It’s common sense. You don’t need to be Napoleon or MacArthur to look at the map and realize that the further east you are, the more reassurance you can provide for those allies and partners on the frontlines, whether it’s—in the northeast it’s the Baltic states, Poland just due east of Germany, or in Bulgaria and Romania in the southeast along the Black Sea. So we need to move a little bit further east. It helps us with the time distance challenges, if you will, in case there is some type of really aggressive action by the Russians.

So that repositioning is strategic. It allows us to do those five imperatives that I mentioned about reassuring allies, deterring Russia, and strengthening NATO, and there are two others, too.

The Poland deal, why is that important, the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement? Because the previous agreement was both outdated and insufficient and didn’t address budgetary matters. So now we have this new agreement and it’s opening up possibilities.

So I mentioned in my remarks there’s now the real opportunity to look at putting the 2nd Cavalry Regiment, or parts of it at least, in Poland, further east, which is what they want. We think it makes sense. I think many NATO countries think that would make sense, as well. But that has opened it up, in addition to the fact that we’re moving a thousand additional troops into Poland. We’ve talked about the V Corps Headquarters, a forward element being stationed there. So that’s just Poland. But we also need to look at the Baltics and the Black Sea region to make sure that we’re meeting those five imperatives along the frontlines of—the frontline trace, if you will, of where we sit vis-à-vis Russia.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thank you for that, Mr. Secretary.

Let’s move to CENTCOM. Let’s move to the Middle East. The UAE and Bahrain normalized relations with Israel, as you said, a groundbreaking agreement at the White House. How does this development impact security cooperation with allies? You know, General Jones at the Atlantic Council for a long time has been calling for something like a Mideast NATO—not patterned entirely on NATO, but groups of—a group of countries in the region coming together in common security framework vis-à-vis Iran. Could this be the beginning of something like that?

MARK T. ESPER: You know, it is a great success by the president and his team in the White House. They’ve just done a great job on this, and we’ll see if more countries follow as well. We’re all hopeful and everybody’s trying to row in that same direction.

I think what’s important about it, it’s not just—it’s a combination of things. It’s the diplomatic opportunities it presents, it’s the security, and it’s the economic to see these Arab states normalize relations with Israel. They do see that there is great potential for economic growth if there is normalization. But the second thing is we’ve reached the point where so many of the countries in the region recognize that the biggest concern they have—we have too—is Iran and its malign behavior through that region now for, what, four decades. That actually spans all the way from Africa across the Middle East into Afghanistan. So we see the common threat of Iran and how do we stand together against that.

The vision would be to have some type of security construct out there where countries on the peninsula, Israel, and others are working together to deter conflict with Iran. And again, if that fails, they’re prepared to work together to do that. We orchestrate much of that now through CENTCOM, if you will, but all those countries have a—have an interest, certainly have concerns: freedom of navigation through the Persian Gulf, freedom of commerce, threats to the sovereignty of countries. I mean, we saw Iran launch attacks against Saudi Arabia last year, on their oil infrastructure. We see Iran playing a heavy hand in Iraq. I mean, again, Iran is all over the region.

So I think folks or countries are recognizing that reality and they’re seeing the other possible benefits, as well, of normalization.

FREDERICK KEMPE: As you look at this—and I see we’re near out of time, so let me move on to—from the Middle East to another question. And that takes us back to the beginning, which is great-power competition. Reading history—and this also comes from someone in the audience—the period of great-power competition after World War I didn’t end up so well. After World War II, ended up better. But between 1945 and the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, you had the Cuban Missile Crisis itself—a near brush with nuclear conflict; you had the Berlin Airlift, which could have landed, if we hadn’t done it, Berlin into Soviet hand. How perilous is this current period where we’re starting a new era? And what are the dangers of miscalculation? Are communications systems in the right frame with China and Russia to steer ourselves around that?

MARK T. ESPER: No, it is very—it is very tricky, particularly in an era of COVID, too, you have on top of that. And so we have to navigate very carefully, we have to collaborate closely with our allies and partners, and we have to send all the right messages. And we have to keep lines of communication open with Beijing and with Moscow and make sure that there is no miscalculation or misunderstanding.

Look, nobody wants to be in this position. You know, we put a lot of work at the end of the Cold War into helping the post-Soviet Russia stand up, right, and then Putin came aboard and took them in a different direction we hadn’t expected. And then, at the same time, you had China. And I have watched China’s rise over the decades. We thought if we—if we worked to open them up, if we let them into institutions like the World Trade Organization, they would—they would liberalize economically, and economic liberalization would bring about political liberalization. That hasn’t happened, and that’s very unfortunate.

So we’re not looking to get into a conflict with either of these countries. We’re not looking to contain China. What we want to see is a peaceful rise, but one within the—within the international rules, the international order, the norms that have benefited us all for—again, for decades, for generations. And right now we see both countries violating them on a continuous basis, and that’s just—we’ve got to stand up and we’ve got to defend this system, and we’ve got to work with them and continue to engage, find areas where we can cooperate. But where we can’t, we’ve got to compete and, if necessary, confront.

And so that’s just the world we live in, and we’ve just got to be prepared for the worst. And being prepared for the worst, again, means strengthening our allies, building partners, enhancing our capacity and our capabilities, everybody investing in that collective security if we’re going to thrive here in the next few decades.

FREDERICK KEMPE: So I’m going to end with my favorite question to ask people like you. I’m not sure it’s the favorite to listen to the answer to, but it’s essentially: What keeps you up late in the evening? Your remarkable speech had a lot of things that would keep me up late in the evening. (Laughs.) And you—and there are a remarkable number of challenges going along. But what is the one that concerns you the most of all of those?

MARK T. ESPER: You know, I will disappoint you because I will say this much. I sleep soundly knowing that we are protected by the best military in the world. And why is that? Because every day young men and women across this country are standing in front of a flag, raising their right hand and swearing an oath to support and defend the Constitution, with their lives if necessary.

And so I’ve had the chance to participate in any number of those swearing-in ceremonies. And when you see that, it really stirs your heart knowing that a lot of young Americans out there are willing to do that, and then serve for years upon years to keep the rest of us safe and to keep this world free.

And so, again, I sleep well knowing we have young men and women doing that. And we have our great DOD civilians. We have our folks in the State Department, the intelligence community, everybody pulling together to keep America safe. So I sleep well.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Well, I sleep pretty well because we have people from all of your services as senior fellows at the Atlantic Council. So that makes us also a stronger organization.

We really appreciate the time you’ve taken, Mr. Secretary. Above all that, we really appreciate your public service. And this statement and speech about allies and steps being taken for allies, I think it really is something that will keep America strong and keep the values and principles that the Atlantic Council has always stood for strongly. So thank you so much, Mr. Secretary.

MARK T. ESPER: Thank you, Fred. Great to be here. Thank you.

(END)

Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

Patrick McGee: Tesla’s Robotaxi Bait and Switch

Elon Musk called self-driving cars a ‘solved problem’ 10 years ago. So how come he’s still working on it? In a new column, Patrick McGee…

Thought Leader: Patrick McGee

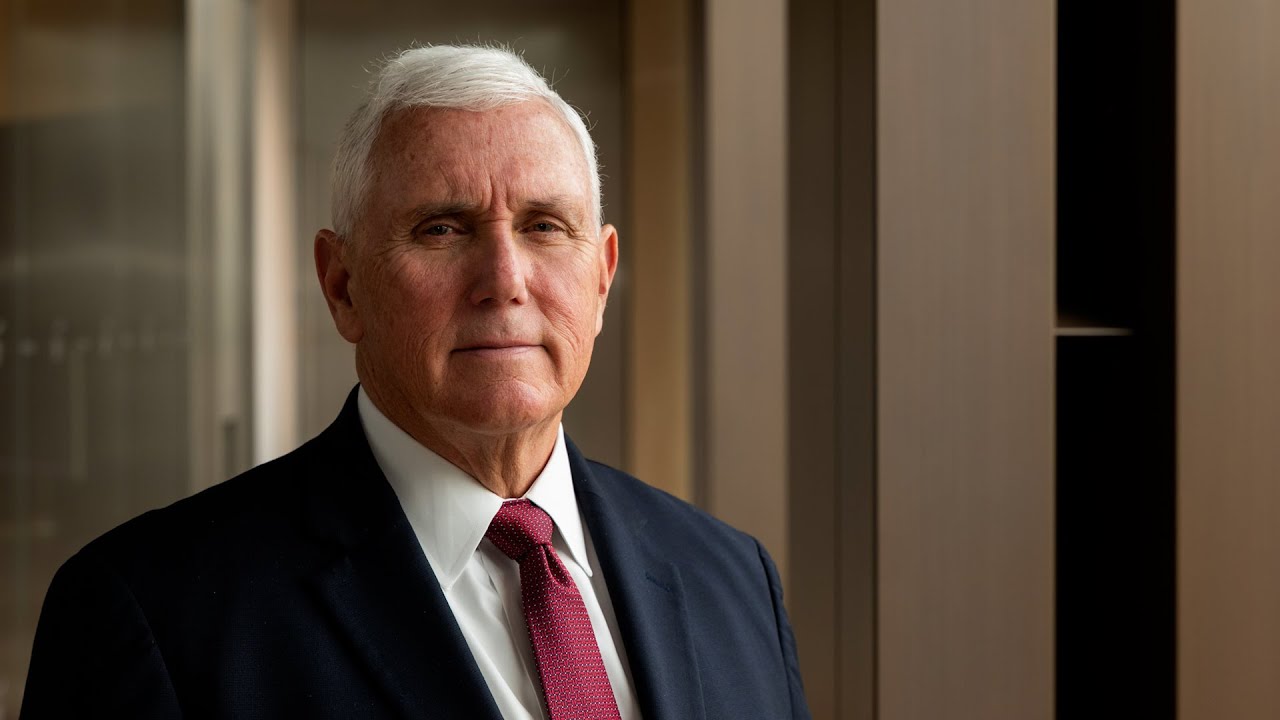

Mike Pence on U.S. Leadership and Global Strategy

Former Vice President of the United States, Mike Pence, shares his thoughts about President Trump’s framework on trying to acquire Greenland, and discusses what he…

Thought Leader: Mike Pence