Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

Discarded cigarette butts on the pavements of central London are an unsightly environmental hazard and costly cleaning burden for the local council. A clever initiative called the Ballot Bin is making inroads into the problem.

Brightly coloured bins with two small slots invite smokers to vote for two light-hearted alternatives. When they choose from options such as “Batman or Superman?” or “Trump’s hair – real or fake?” the mounting pile of butts in each transparent compartment reveals the winner. It’s a clever and innovative solution, dreamed up by an environmental entrepreneur called Trewin Restorick, and it’s working. The Ballot Bin has slashed cigarette litter and has now been adopted in 27 countries.

Restorick’s story provides a neat opening for Josh Linkner in his book Big Little Breakthroughs. Popular notions of innovation celebrate big eureka moments, but small changes in habits can have big effects when multiplied. The Ballot Bin alone won’t solve London’s litter problem, but start thinking differently and sustain it as a habit and you can reap rewards, is his message.

“Big ideas are often out of reach and are very risky. Instead, everyone should look to cultivate everyday innovation. This micro-innovation is much more accessible, it helps us to build critical skills, and these little ideas in time build up to big things,” he tells The Irish Times, adding, “It’s the volume of ideas not the magnitude of any single one that enables you to outperform industry norms.”

Linkner is the founder of several companies including ePrize and Detroit Venture Partner, a VC that aims to rebuild urban areas through technology and entrepreneurship, and has published a number of bestselling books on innovation. He says he spent 1,000 hours researching his latest, talking to highly successful people across a variety of genres.

In colouring in his points, Linker draws heavily on influences from outside the world of business, with entertainment providing rich material. Going against the grain sometimes works really well, he notes, as he presents us with the story of the unlikely white rap artist called Lil Dickey whose brand image epitomises the polar opposite characteristics of boastful, blingy rap stars, including a penchant for dispensing penny-pinching tips.

There’s a serious point to this, he notes, outlining a technique he calls the Judo Flip, in which you take a sheet of paper and on one side you write what everyone else does and on the other you list the exact opposite, however strange that that may appear.

“It’s good to start from the perspective of ‘everyone else does this, so do the opposite’. You don’t need to be completely opposite in every area of your business to win but exploring oppositional approaches may help you surface one or two actionable ideas.”

Linkner suggests a process of creative destruction, taking apart an existing product or business and questioning its foundations. This should lead to questions such as: What was the thinking that led to its initial creation? Why did it work in the past? How have customer needs changed since it was created? What beliefs are currently holding this together that can be challenged?

Habits that induce creativity vary and in some cases are bizarre. Leonardo da Vinci took five naps a day (science validates his approach), the playwright Tom Stoppard literally chained himself to a desk for seven hours to write, while the German writer Friedrich Schiller filled his desk drawers with rotting apples, requiring the decaying stench before writing a single word.

In some cases, it is a matter of sheer doggedness, as in the punishing – but ultimately rewarding – regime of practice and refinement adopted by Lady Gaga, long before she became a star. As the bestselling author Seth Godin puts it: “Lots and lots of people are creative but you are only going to become a professional if you do it when you are not in the mood.”

Experiments are important, Linkner maintains. “Leaders should be testing five or six things a week. The optimal number of failed experiments is not zero. If that’s your number, you are not doing enough.”

Markets are pricing in innovation practice, he notes, citing an MIT study which contrasts Tesla and General Motors. GM should be more valuable based on its volume, longer history of profits and deeper infrastructure, but Tesla’s innovation premium accounts for its higher valuation.

The same innovation premium applies at an individual level, too. “The so-called hard skills of the past have become commoditised, automated and outsourced, but you can’t outsource creative thought,” he observes.

The ability to sense other people’s feelings and emotions is another valuable asset when it comes to innovation. Linkner writes about how marketing professors Kelly Herd from the University of Connecticut and Ravi Mehta set out to measure how empathy affects creativity.

In an experiment involving more than 200 adult participants, the group were asked to generate ideas for a new potato chip for pregnant women. Half the group were instructed to generate ideas using logic and cognitive skills while the other half was instructed to let empathy guide their way. The empathetic cohorts were asked to close their eyes and imagine what the women were going through during their pregnancy and how they would feel when eating the snack.

A panel of experts was enlisted to judge the ideas, with the empathetic group dramatically outperforming the logic-based ones. The empathy exercise yielded flavour ideas such as pickles and ice cream, something a mum-to-be might be craving, while other leftfield suggestions were sushi with wasabi, and a margarita, noting the advice to women to avoid raw fish and alcohol but recognising that these were the very things they might be craving. Eliciting empathy has inherent value in maximising creativity, the study concluded.

In his book Big Little Breakthroughs, Linkner notes the characteristics of successful innovators and offers the following advice:

1. Fall in love with the problem Rather than focusing on a specific solution, take time to carefully examine and understand the challenge at hand. This means being more committed to solving the problem than to a particular manner of solving it and remaining flexible and open-minded in order to find the optimal approach.

2. Start before you’re ready Everyday innovators take the initiative to get started now instead of waiting for permission, detailed instructions, or ideal conditions. They are willing to course-correct along the way, adapt to changing circumstances in real time, and operate with agility.

3. Open a test kitchen Innovation is both strengthened and de-risked through experimentation. By building a framework and conditions for testing and creative exploration, ideas are cultivated and optimised.

4. Break it to fix it Ditching the “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” maxim, everyday innovators proactively deconstruct, examine, and rebuild to deliver superior products, systems, processes and works of art.

5. Reach for weird Preferring the unexpected approaches to the obvious ones, everyday innovators challenge conventional wisdom by searching for unorthodox ideas. They have a penchant for discovering oddball, sometimes even bizarre ideas in order to discover better outcomes.

6. Use every drop of toothpaste Take a scrappy approach of doing more with less. Counterintuitively, being resource-constrained can fuel creative breakthroughs. Resourcefulness and ingenuity become powerful weapons in the fight for superior innovation.

7. Don’t forget the dinner mint Adding small, creative flourishes can yield significantly improved results. An extra dose of surprise and delight enables new invention and competitive edge.

8. Fall seven times, stand eight Realising that setbacks are inevitable, everyday innovators use creative resilience to overcome adversity. Mistakes are a natural and important part of the innovation process and can be flipped into advantages when studied and embraced.

Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

Patrick McGee: Tesla’s Robotaxi Bait and Switch

Elon Musk called self-driving cars a ‘solved problem’ 10 years ago. So how come he’s still working on it? In a new column, Patrick McGee…

Thought Leader: Patrick McGee

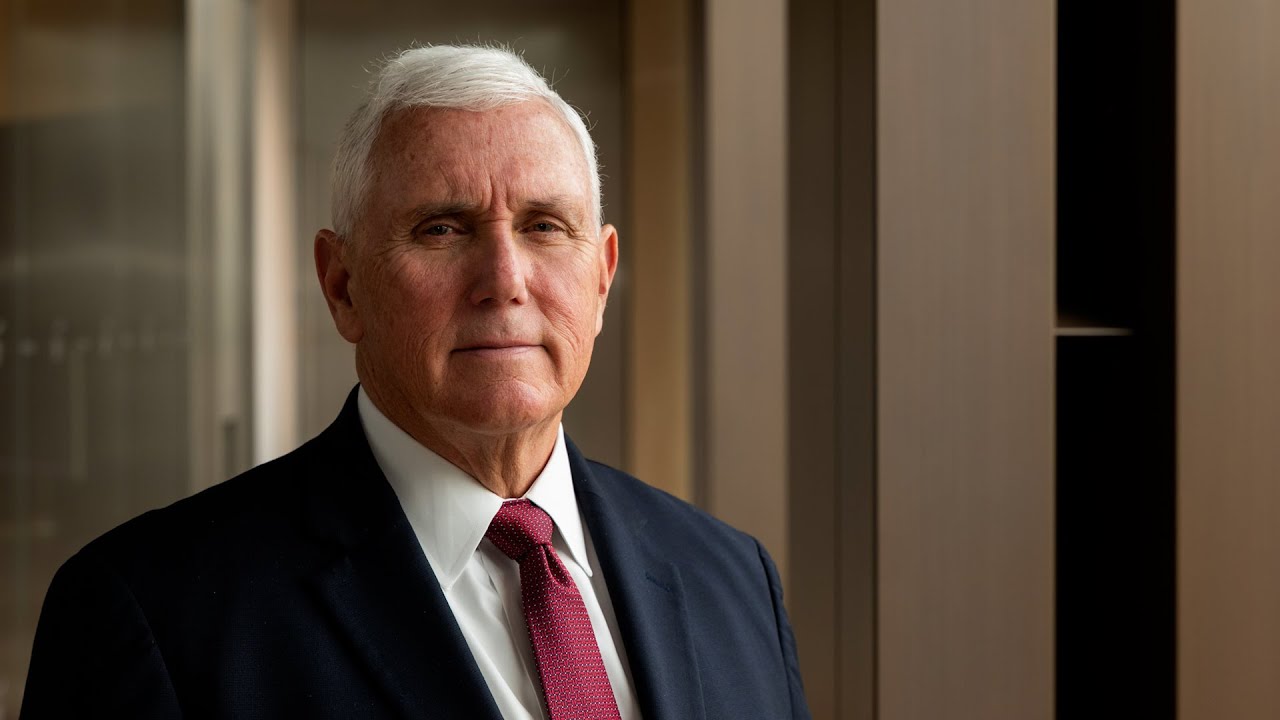

Mike Pence on U.S. Leadership and Global Strategy

Former Vice President of the United States, Mike Pence, shares his thoughts about President Trump’s framework on trying to acquire Greenland, and discusses what he…

Thought Leader: Mike Pence