Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

To meet with the former national security adviser, one must pass through an imposing security detail. Like the country he served, Robert O’Brien has friends abroad, but also more than a few enemies.

Once inside the former ambassador’s Utah residence, O’Brien is quick with a handshake and an offer of Fiji Water. Tieless, he’s decked in what appear to be 1953 Gucci horsebit loafers, a navy suit and golden Brooks Brothers cufflinks dangling from a crisply-ironed shirt. The look might be described as diplomat casual.

Lining O’Brien’s walls are talismanic reminders of his service from 2019 to 2021 as national security adviser — and from 2018 to 2019, as the special presidential envoy for hostage affairs. The latter role, he tells me, thrust him into negotiation efforts to bring some 55 American hostages home. The hardest part of the job, he admits, is thinking about “the people who didn’t get home.”

Inside O’Brien’s carefully arranged office are various political tells. Positioned alongside patriotic ornaments, and above a foot-tall statue of Richard Nixon, is a framed print of a Winston Churchill war-era speech. It serves as the backdrop for his home office DIY TV studio.

O’Brien has a Fox News television appearance scheduled during our interview, and he permits me to hover as he sits down and checks his connection with the studio in New York City.

“OK, we’re 45 seconds,” he tells his wife, Lo-Mari. She responds with whispered instructions (“tip your chin down,” “pull your jacket together”).

When O’Brien goes live he stares unflinchingly into the camera. And, despite the intensity of live cable television — Fox doesn’t tell O’Brien the subject of the interview ahead of time — the diplomat attorney comments on the news of the day with the considered staccato of someone accustomed to briefing the commander in chief.

Earlier this year, O’Brien’s name was floated in The Washington Post by columnist and well-known radio personality Hugh Hewitt as a possible contender for vice president. O’Brien is an ideal running mate, Hewitt reiterated to me over the phone, because of his national security mastery at a time when foreign policy is critical. And besides, Hewitt said, his membership in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints could help Donald Trump with voters in Western swing states like Nevada and Arizona, where he struggled in 2020.

Others with whom I spoke said O’Brien was one of the most likely picks for secretary of state under a second Trump administration, with one former ambassador saying he “is clearly the front-runner.”

O’Brien had extensive access to former President Trump during his time in the West Wing. He was stationed around the corner from the Oval Office, and was sometimes Trump’s first and last phone call of the day. Importantly, unlike many others in the Trump administration, including the two previous national security advisers, O’Brien still appears to be in the former president’s good graces, defending even Trump’s most unilateral foreign policy positions.

“My view is peace through strength,” O’Brien tells me. “I think Donald Trump called it America First. But it was basically the Reagan view of peace through strength, of being tough and asserting our interests and having the will in the world to back that up.”

O’Brien describes himself as a Reagan-era Republican. He was at the Republican National Committee when Reagan was running for reelection and served as an adviser to Sen. Mitt Romney on both of his presidential campaigns. But where some old guard Republicans became never-Trumpers, O’Brien saw a throughline from the GOP of Reagan to its current iteration and appreciated the party’s move to a blue-collar populist platform.

With the GOP in flux, this faith that the Republican Party is — and always has been — the defender of peace through strength is one reason O’Brien’s star has risen in the party, but if he’s put on the Republican Party ticket in 2024, it may also be what helps keep the party from splintering apart.

TV camera, monitor and bookshelf backlight switch off, and I follow O’Brien out of his home office. In the hallway is an aging Old Glory framed on the wall. “This was on a vessel that landed on Normandy,” Lo-Mari tells me. I have no way of independently verifying the claim, but the flag looks the part.

Historical items like this blanket O’Brien’s home. When we sit down to talk, his shock of short-cropped white hair is outlined by a view of the valley below. O’Brien is relaxed, his voice sometimes drifting to a mumble and then back again to clarity as he responds to rumors that he is auditioning for vice president or running for U.S. Senate in his new home state, Utah.

“No,” O’Brien smiles. “Utah is blessed with really an abundance of great political leaders and so they don’t need another person jumping in the race.”

It was the state’s “tremendous” conservative leadership, as well as its friendly business environment, he says, that drew him here from his native California. And while he acknowledges a great “respect for … elected officials” and their sacrifices, after mulling a 2024 presidential run, O’Brien decided elected office wasn’t for him — “It’s not for me on the elected side.”

But Hewitt says not to count O’Brien out of a Senate race quite yet, particularly if Romney bows out of the race. In politics, it’s always a “no, until it’s a yes,” he tells me.

And what about a cabinet position, I ask. “When the president asks you to do something, you salute and say ‘Yes, sir.’”

O’Brien voted for Trump in 2016, endorsed him in 2020 and says the country would be better off in two years if Trump, as the Republican nominee, is elected over his Democratic opponent. O’Brien rejects the narrative Trump’s rise within the GOP has permanently disrupted Reagan’s coalition of fiscal conservatives, social traditionalists and foreign policy hawks, saying “it’s more of a media thing than a real thing.”

While he readily admits Trump has been a catalyst for change within the party, O’Brien says it has been “for the better,” replacing a “Bush-Rockefeller” establishment with “a Ronald Reagan-Donald Trump establishment” that appeals more to working-class individuals.

Part of this shift, O’Brien says, included a bolder, if less interventionist, approach to foreign policy, one in which O’Brien found himself at the center of such key Trump administration accomplishments as the Abraham Accords, the Kosovo and Serbia normalization agreements and the elimination of some of the world’s most dangerous terrorist leaders, he says.

Typical of O’Brien, he can’t help but talk about these moves without bringing up his childhood hero Churchill, who he believes was instrumental in expanding Britain’s military force and safeguarding its freedom for generations to come by following a similar foreign policy playbook.

O’Brien spent his childhood in the central California city of Santa Rosa. His father, a former Marine who later worked for a bank, was a Reagan acolyte who made international affairs a regular topic of discussion at the O’Brien family dinner table.

“We grew up Catholic but the religion of the house was America,” O’Brien said.

So, it was no surprise when O’Brien chose to study political science instead of attending a theological seminary.

After his first year at the University of California, Los Angeles, O’Brien said he earned a scholarship for the remainder of his undergraduate career. O’Brien also later won a Rotary International scholarship to study in South Africa, where he met his wife, Lo-Mari. Following his graduation from UCLA, O’Brien went on to law school at UC Berkeley.

Growing up, O’Brien had several friends who were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and it was their patriotism more than anything else, he said, that stood out to him. When these friends left for Brigham Young University, O’Brien thought he had heard the last of the church. But after learning that if he attended a church-run institute class he could get a coveted UCLA parking spot, O’Brien’s interest was piqued.

He decided to spend one semester at BYU, where he joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, in no small part, he says, because of the example of political science professors who were at the top of their fields but also exhibited “tremendous” faith in the way they interacted with the world.

He pointed to figures such as Vice President Mike Pence and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo who incorporated prayer and scripture study into their daily schedule as other such examples. “You could walk around the White House and see Bibles and scriptures on people’s desks,” he said.

I spot portraits of O’Brien’s three children in scouting apparel, posed in front of the Stars and Stripes. O’Brien’s wife, Lo-Mari — who Hewitt said would be “dynamite on the (campaign) trail” as second lady — discusses each of them with the pride only a mother can convey.

Robert, the youngest of the three, planned on serving a church mission and joining the ROTC but died in a tragic accident in 2015 shortly after finishing high school. His desire to serve his county, however, was a legacy he passed on to his older sisters.

The middle child, Lauren, studied aviation at Utah Valley University and is now an Air Force pilot. The O’Brien’s firstborn, Margaret, attended BYU law school and became a JAG officer with the Georgia National Guard.

O’Brien also got his start as a JAG officer after graduating from law school, handling government claims against Iraq arising out of the first Gulf War for the United Nations Security Council in Geneva, Switzerland. Over the next three decades, O’Brien worked at various law firms in LA, where many of his cases dealt with international arbitration.

Despite not working as a career diplomat or elected official, O’Brien quickly became a well-known name in conservative national security circles, with political appointments coming in rapid succession.

In 2005, O’Brien was nominated by President George W. Bush to be an alternative representative for the U.S. at the 60th session of the United Nations general assembly. Soon after, he became a founding co-chairman of the Department of State’s Partnership for Justice Reform in Afghanistan. And from 2008 to 2011, O’Brien served on the Department of State’s Cultural Property Advisory Committee.

After dipping his toes in electoral politics as a legal counsel for Bush’s 2004 reelection effort, O’Brien promised his wife he would steer clear of presidential campaigns. But a friendship with Romney’s son pulled O’Brien into Romney’s circle of advisers during his 2008 and 2012 presidential campaigns.

O’Brien’s national security expertise were again sought during the 2016 presidential election cycle, when he served as a senior foreign policy adviser to former Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker and Texas Sen. Ted Cruz.

O’Brien had a reputation as a foreign policy hawk, critical of the Obama administration’s posture toward Iran and China — prefiguring Trump’s later stances — and emphatical about the strategy of “peace through strength,” the Reaganite catchphrase O’Brien employed at least five times during our conversation.

“The best American presidents, I think, use peace through strength,” O’Brien said. “The goal is for America to be so strong that our adversaries don’t challenge us and don’t draw us into war. … (Trump) was the first president since Reagan … where American troops weren’t deployed in new combat operations.”

O’Brien’s first call from the White House was in 2017 when he was told he was being considered for secretary of the Navy, his “dream job,” and a nearly identical position to the one Churchill filled prior to World War I.

While O’Brien didn’t get the job, he was later able to work toward revitalizing America’s naval force as Trump’s national security adviser, spearheading the effort to increase the Navy’s ship count from just under 300 to over 350.

The next call came a year later. O’Brien was requested to fill the administration’s final ambassadorship as the special presidential envoy for hostage affairs. His initial inclination was to decline, O’Brien said, but the thought of individual Americans being held hostage entered his mind.

“And I thought, if I can get one person home, yeah, it’s worth doing,” O’Brien said. “My only goal was to get Americans home.”

O’Brien was known to carry around baseball cards with the names and faces of those being held captive, Edward McMullen, former ambassador to Switzerland and Liechtenstein from 2017 to 2021, told me.

O’Brien wanted everyone he worked with to “understand the family and what they’re going through … to keep the mission, front and center,” McMullen said. Working with Trump as the special presidential envoy for hostage affairs led to his subsequent appointment.

O’Brien took office as the 27th United States national security adviser in September 2019. Whereas his three predecessors had all run afoul of Trump, O’Brien’s lawyerly discretion seemed to better fit the president’s personality.

“When I worked with President Trump, I thought it was my job as his chief foreign policy adviser to give him the best advice … as opposed to trying to put my thumb on the scale in the cabinet debates, and then make sure his policies were implemented,” O’Brien said.

However, speculation that Trump favored O’Brien for his looks and deferential attitude, rather than his competence or credentials, quickly surfaced after his appointment. This view was bolstered for some when O’Brien took to defending Trump’s most controversial foreign policy decisions, such as pardoning a Navy Seal convicted of war crimes, killing a top Iranian general in a drone strike and banning travel from multiple countries at the onset of COVID-19.

But according to Gregory Smith, former deputy director of political affairs at the White House from 2019-2021 and who has worked with O’Brien after leaving the White House, it’s simply not in O’Brien’s nature to be a yes-man.

“I think he’s the type of person that’s never afraid to give you an opinion that differs from yours,” Smith said. “But he’s ultimately going to support the final decision that’s made.”

It was O’Brien’s willingness to challenge Trump’s views in private and not be “one of the sycophants who told him what he wanted to hear” that earned O’Brien the former president’s trust and respect, McMullen said.

O’Brien counts pressuring NATO allies to increase their share of defense spending; reviving the country’s hypersonic missile programs and enabling the Abraham Accords, which formally normalized diplomatic relations between Israel and the United Arab Emirates and several other predominantly Muslim nations — an accomplishment Israel Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called “a new dawn of peace” — as some of the major national security wins during his tenure.

O’Brien remembers leading a delegation of officials in the first commercial flight from Israel to the United Arab Emirates, which required flying over Saudi Arabia, the most powerful of the Arab nations that had long refused to recognize Israel’s statehood.

As the plane crossed over into Arab airspace, with the threat of violent retaliation now absent for the first time, O’Brien said the emotions were palpable.

“These were tough guys,” O’Brien said of the Israeli passengers. “And they were teary eyed, they were very moved by the fact that we were flying into Saudi Arabia.”

For his central role in mediating the Abraham Accord negotiations, O’Brien was awarded the National Security Medal and a tree was planted at the John F. Kennedy Memorial Forest in Jerusalem in his honor.

At the tail end of his time as national security adviser, Utah Sen. Mike Lee told Politico that O’Brien was “one of the most powerful people in Washington, even though he is perhaps not as widely known as he should be given how much influence he has.”

Others, however, have criticized O’Brien’s time in office. In September 2020, a whistleblower alleged O’Brien had instructed intelligence officials to shift their focus away from potential Russian interference in the 2016 election and toward Chinese and Iranian political interference — a claim the White House and Department of Homeland Security denied. And in October of the same year, O’Brien was criticized for making taxpayer-funded trips in what some claimed was an effort to boost Trump in swing states.

O’Brien said his job was not political. His role was to analyze and advise on national security matters for the safety all Americans.

“Churchill had the courage to stand up against the Nazis all alone, and not give up and not take a good deal, but to fight for democracy. … I think he saved the world,” O’Brien said in an impromptu soliloquy that included three memorized Churchill quotes.

But O’Brien is the first to admit that Churchill had his flaws. O’Brien also cedes many of the criticisms against his former boss, Donald Trump. But O’Brien asserts claims of Trump being singularly responsible for political polarization or electoral mistrust as overlooking equivalent behavior on the other side of the aisle.

When asked whether the former president’s spurious claims about winning the 2020 presidential election have affected his support for Trump’s reelection, O’Brien said they do not.

“We’re in a democracy, people have freedom of speech, and if they don’t like the way an election is conducted, they can complain about it,” O’Brien said. “People are allowed to voice their opinions. And look, the voters will decide if President Trump is fit for office or not.”

O’Brien himself does not believe that the 2020 election was stolen, but says there must be a greater effort to create transparency around, and trust in, the electoral process so it ceases to be a partisan issue.

“We’ve got to get to a place where Americans, all Americans, have confidence in the election,” O’Brien said. “Otherwise, we’re gonna tear ourselves apart as a country.”

While standing firmly by the former president’s side, O’Brien has made a point of reaching across ideological divides, sustaining deep friendships with Democrats, including the famed actor, and well-known progressive, Sean Penn.

The two have hosted events in support of veterans and have appeared together on Fox News and various panels to discuss the importance of bipartisan work on the problems that unite us.

“I think we got more in common as Americans and more in common as Republicans than things that divide us,” O’Brien said.

The ambassador remains deeply invested in combating hostage diplomacy around the world and currently co-chairs a Center for Strategic and International Studies commission that will release a report later this year with policy recommendations for disincentivizing hostage-taking and maintaining peace by multiplying in strength

According to Smith, who is now chief of staff to Rep. Eli Crane, R-Ariz., O’Brien has a unique “megaphone” to help ensure “the pivot that the Republican Party makes” is a “return to Reaganism” and “not a departure.”

As for what comes next in the political sphere, O’Brien says he doesn’t know the future — which is what “makes life interesting.” But he believes America must act unitedly and with more urgency to remain strong abroad.

It’s the same sentiment which courses through the black and red ink of Churchill’s war-time poster, clearly visible in the background but just out of focus during O’Brien’s Fox News hit:

“COME THEN LET US TO THE TASK TO THE BATTLE & THE TOIL,” it reads, with the first line capitalized. “Each to Our Part Each to Our Station, Fill the Armies, Rule the Air, … Build the Ships, … There is not a week, nor a day, nor an hour to be lost.”

Peace through strength is the message, he says, no matter his political post.

“A strong American military and a strong American foreign policy to keep our country safe and keep our allies safe,” O’Brien said. “And what comes after that, it all depends on who the American people will elect as their leader.”

Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

Patrick McGee: Tesla’s Robotaxi Bait and Switch

Elon Musk called self-driving cars a ‘solved problem’ 10 years ago. So how come he’s still working on it? In a new column, Patrick McGee…

Thought Leader: Patrick McGee

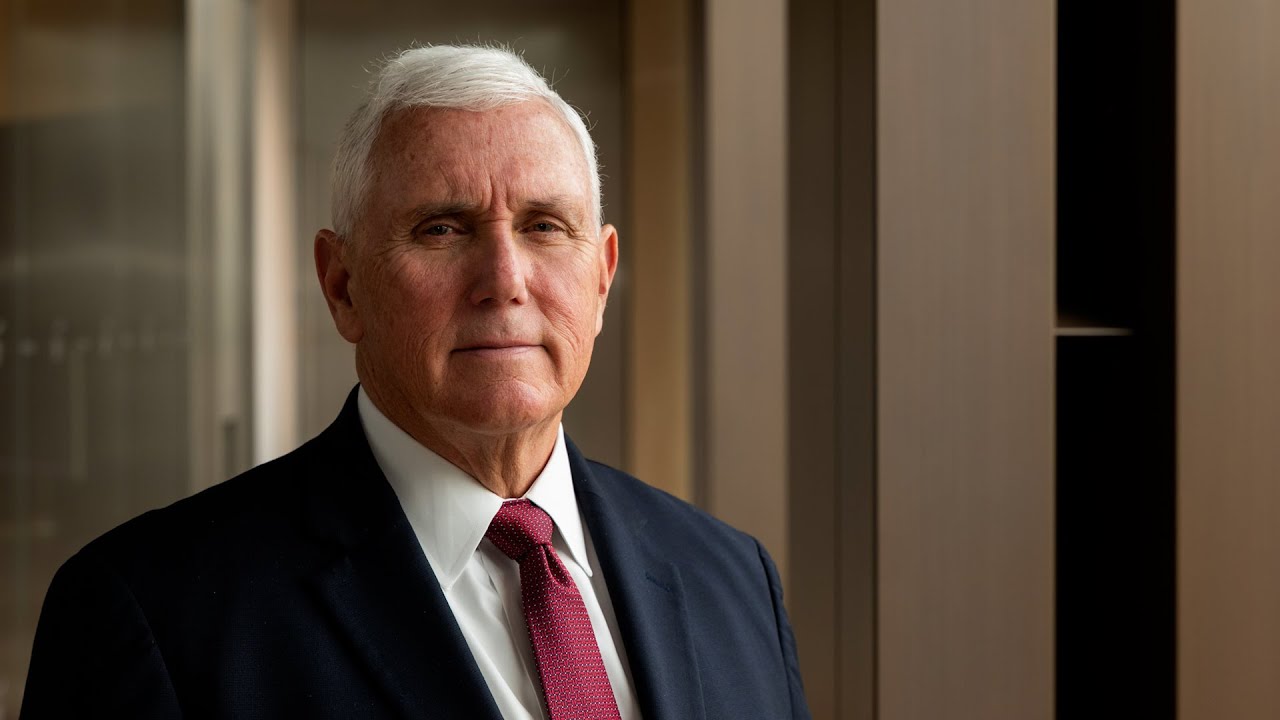

Mike Pence on U.S. Leadership and Global Strategy

Former Vice President of the United States, Mike Pence, shares his thoughts about President Trump’s framework on trying to acquire Greenland, and discusses what he…

Thought Leader: Mike Pence