Mike Pence on Leadership and the Future of the Republican Party

Former US Vice President Mike Pence looks back on the events of January 6 2021, his final days in office with President Trump and his…

Thought Leader: Mike Pence

Never underestimate the power of the revolutionary crowd. It has swept through Paris time and again — in 1789, 1830, 1848, 1871 and 1968 — unseating kings, emperors and presidents. In Petrograd and Moscow in 1917 the crowd toppled the tsar and then brought Lenin to power. Those who took to the streets in Leipzig and Berlin in 1989 know what the revolutionary crowd can achieve — as do those who were in Cairo’s Tahrir Square in 2011 (and again in 2013) or Kyiv’s Maidan in 2014.

In China, too, the crowd has played a revolutionary role on more than one occasion. Its unexpected reappearance in multiple Chinese cities last week was therefore an event of great consequence.

The proliferation of the smartphone and social media allow us to study this historical phenomenon with unprecedented precision. Consider this extraordinary scene from Shanghai last Saturday.

The leader shouts, “gongchangdang” (Communist Party) and the crowd responds “xiatai!” (step down! or down with it!) Then he shouts, “Xi Jinping” and they also respond with “xiatai!” The first call that doesn’t elicit a strong response, strangely, is “fengchengzhi” (lockdown). Then the group shouts, “Liberate Urumqi!” and then “Liberate Xinjiang!” Finally, they shout “Liberate the whole of China!”

Last week, I asked William Kirby, T. M. Chang Professor of China Studies at Harvard, what he thought. Such explicitly anti-government language was extraordinarily rare in the history of the People’s Republic, he said. Not even at the height of the June 1989 democracy movement did protesters explicitly call for the overthrow of the Party and its general secretary.

Though I am far less expert than my friend Bill Kirby, I spent five years as a visiting professor at Tsinghua, one of the two big universities in Beijing. So I immediately recognized the Zijing dining hall outside which Tsinghua students gathered last weekend. Their chants were somewhat different: “Democracy, rule of law, freedom of expression, scientific reason, integration with the world!” You might think that’s just the kind of thing Tsinghua’s famously nerdy students would chant at a protest — until you realized that in 2016 Xi Jinping called on universities to “adhere to correct political orientation,” eschewing the discussion of Western ideas such as democracy, rule of law and freedom of expression. So this was explicit defiance of “Xi Jinping Thought.”

Other Tsinghua students came up with an even nerdier form protest by holding up sheets of paper with printouts of the Friedmann equations — politically significant either because the Russian physicist’s surname sounds like “freed man” or because the equations signify that “the basic reality of the universe is constant, eternal expansion, or put another way, opening up.”

These highly cerebral crowds are a far cry from the Parisian sans-culottes or the Bolsheviks, of course. The Tsinghua students have many admirable qualities, but you would not count on them to storm a Bastille or a Winter Palace. And indeed, it was no surprise that, given the Chinese authorities’ unprecedented powers of social control and surveillance, the protests were suppressed quite swiftly and without much in the way of brutal force.

Yet, as has often happened in Chinese history, these student demonstrations were significant as part of a much broader wave of discontent. The catalyst could hardly have been further removed from the Tsinghua campus: a fire in a 21-story apartment building in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang.

What in normal times would have been a straightforward emergency took firefighters three hours to bring under control, because of obstructions due directly or indirectly to Covid-related restrictions. At least ten people perished. Prior to the blaze, Urumqi had been under lockdown for 100 days.

In the rest of the world, the Covid-19 pandemic is effectively over, even as the virus continues to mutate, circulate and sicken. A combination of vaccines and immunity acquired through infection has reduced the disease to a manageable problem. Social and economic normality have to a large extent been restored.

Not in China. Three years after the pandemic began in the city of Wuhan, the often draconian non-pharmaceutical restrictions that came to be known as “lockdown” remain in place. The centralized quarantine system currently houses more than 1 million people. All over this vast country, people have had enough of living under virtual house arrest, subjected to constant testing and contact tracing — discontent that has erupted into unrest from Urumqi in the west to Zhengzhou in central China to Guanghzhou in the south.

Popular protest is far from unusual in China, to be sure. According to William Hurst, Chong Hua Professor of Chinese Development at Cambridge, it takes five different forms: labor protest, rural protest, student protest, urban governance protest, and systematic political dissent. The remarkable thing about last weekend was that protesters “appeared on the streets in multiple cities with apparent knowledge of what is happening in other parts of the country … all mobilizing around Covid … [but] refracted through distinct lenses.”

Such conjunctures of discontent have been momentous turning points in Chinese history, even if the protests were snuffed out. On May 4, 1919, Beijing students gathered in Tiananmen Square to protest the Treaty of Versailles, which allowed Japan to retain territories in Shandong that Germany had previously controlled. Members of the “New Culture Movement” called for a rejection of traditional Confucian values and the adoption of Western ideals of “Mr. Science” and “Mr. Democracy.” Attempts to crush the protests led to a wave of strikes, including in Shanghai, then the country’s most economically important metropolis. Order was ultimately restored. But among the leaders of the movement were Li Dazhao and Chen Duxiu, who went on two years later to found the Chinese Communist Party.

In the Cultural Revolution unleashed by Mao Zedong against the Party’s bureaucracy in the 1960s, Beijing students were the most militant of the Red Guards.

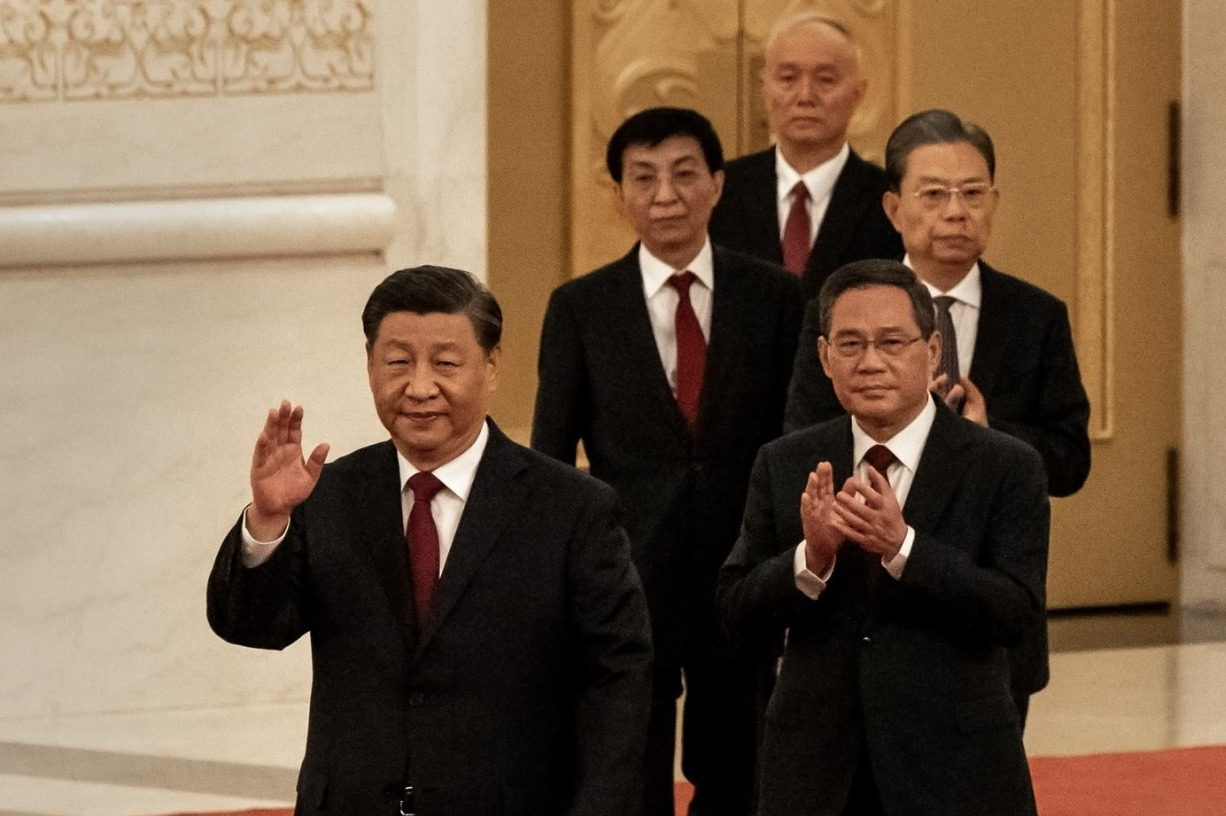

Fast forward to June 1989, when a very different wave of protests once again centered on students in Tiananmen Square. The movement had in fact started in April as spontaneous public “mourning” over the death of Hu Yaobang, general secretary from 1982 to 1987. As in 1919 and as today, a wide range of popular grievances suddenly seemed to find their focal point in the students of the capital. When the news broke on Tuesday that former leader Jiang Zemin died, there was speculation that the event might have a similar catalytic effect — especially when the official statement on Jiang’s passing praised him for ensuring a peaceful transition of power to Hu Jintao, the man humiliated by Xi Jinping at October’s Party Congress, and for stepping down voluntarily as head of the military in 2004.

John Culver of the Atlantic Council, a veteran CIA specialist on China, was moved to comment: “I’m not a mystical person but it felt that way [in the lead up to Tiananmen], like events were riding an iron rail to the bloody finale.”

In The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1895), the French social theorist Gustave Le Bon argued that a crowd was more than the sum of its individual members. Because of three characteristic features of crowds — the anonymity of the individual, the propensity for contagion between individuals, and the crowd’s suggestibility — he suggested the existence of a collective crowd mind. “The substitution of the unconscious action of crowds for the conscious activity of individuals,” wrote Le Bon, “is one of the principal characteristics of the present age.” A somewhat different argument, colored by the experience of growing up as a Jew in interwar Austria, can be found in Elias Canetti’s Crowds and Power (1960). For Canetti, the tendency of all crowds is toward density, direction, growth, and equality. A crowd resembles a besieged city, subject to the pressures of defection from within and hostility from without. “In the crowd,” wrote Canetti, “the individual feels that he is transcending the limits of his own person. He has a sense of relief.” But the resulting “discharge” could be destructive.

Perhaps forgetful of the crowd’s somewhat mixed historical record, the Western media tend to side with young people when they take to the streets. I well recall the gushing enthusiasm of the New York Times for the protests of the misnamed “Arab Spring.” Western coverage of the so-called color revolutions — Georgia’s Rose Revolution (2003), Ukraine’s Orange Revolution (2004), and Kyrgyzstan’s Tulip Revolution (2005) — was generally uncritical. I myself cheered when the Kyiv crowd drove out their corrupt president, Viktor Yanukovych, in the “Euromaidan” revolution of 2014, underestimating how swiftly that would trigger Russian intervention.

The crowd remains a potent force in Latin America, too — in recent years, forcing a revision of the Chilean constitution, the abandonment of a Colombian tax plan, the rejection of an Ecuadorian agreement with the International Monetary Fund, the reform of fuel subsidies in Peru. (For a comprehensive list of the roughly 400 antigovernment protests around the world since 2017, see Carnegie’s useful Global Protest Tracker. David Clark and Patrick Reagan have a dataset that goes back to 1990, which reveals a global surge in protest since around 2010.)

Crowds have played an unusually important role in recent American politics. The crowds that formed in so many American cities in the wake of George Floyd’s murder on May 25, 2020, expressed a widespread revulsion against racial discrimination and violence. Yet their conduct had unforeseen consequences, not least the demoralization if not defunding of the police and a significant wave of violent crime. The invasion of the Capitol by a crowd of supporters of Donald Trump on January 6, 2021, was a bungled attempt to overturn the result of the 2020 presidential election. Yet its net result has probably been to lower Trump’s chances of reelection in 2024.

That crowds are not always benign had already been made abundantly clear by the emergence of online mobs enabled and empowered by the Internet and the smartphone. As Renée DiResta has argued, the digital crowd that emerged in the 2010s was fundamentally different from the crowd of the 1930s that so fascinated and appalled Canetti. In her formulation:

1. The crowd always wants to grow — and always can, unfettered by physical limitations.

2. Within the crowd there is equality — but higher levels of deception, suspicion, and manipulation.

3. The crowd loves density — and digital identities can be more closely packed.

4. The crowd needs a direction — and clickbait makes directions cheap to manufacture.

In a brilliant new essay, “How Online Mobs Act Like Flocks of Birds,” DiResta draws an analogy between our online behavior and the murmuration of starlings, which is especially apt considering the name of the most controversial social media site. What we see on Twitter (and on other platforms) is “the rapid transmission of local behavioral response to neighbors.” The reason this so often produces conspiracy theories and vituperation, she suggests, has much more to do with network curation techniques than with defects of content moderation. “Our current system of communications infrastructure and nudges” may be a “death spiral,” she suggests, because it leads to “toxic emergent behaviors.”

With all that in mind, let’s turn back to China. The authorities’ initial response to last weekend’s protests was surprising. What were obviously government-controlled bots suddenly flooded Chinese social media with escort ads, making it more difficult for users to access or share information about the mass protests.

Initially, the Party held the line: “Our prevention and control policies can stand the test of history, and our prevention and control measures are scientific and effective, the most economical and the most effective,” wrote the “Voice of the Party Center” (zhongyin) in the People’s Daily on November 26.

But then, very surprisingly, Guangzhou eased restrictions in at least four districts. Zhengzhou also announced that residents who did not need to commute to work (such as students and elderly) would be exempted from mass PCR tests. In Chongqing, too, officials announced measures to limit testing requirements and prevent lockdowns from being extended. Other cities, including Beijing and the northern city of Shijiazhuang, eased their testing requirements and reopened malls and supermarkets. Also writing for Bloomberg, Chang Shu and David Qu pronounced that China was now “resolved to exit Covid Zero.” By the end of the first half of the next year, the Chinese economy would be “free of any material Covid curbs.”

Wait, did the crowd just win? It certainly looks that way. On Wednesday, in a complete reversal of her position the week before, Vice Premier Sun Chunlan declared that the virus’s “weakening pathogenicity” had created a “new situation” with “new tasks” for the nation, in a statement that did not use the phrase “dynamic zero COVID.” “Most Chinese people are no longer afraid of being infected,” tweeted the former editor of the pro-CCP Global Times, Hu Xijin. “China may walk out of the shadow of COVID-19 sooner than expected.”

It seems to me that President Xi and the CCP leadership confront a classic trilemma. They would like three things, but they can have at most two. (In economics, the best-known trilemma or “impossible trinity” involves a choice among a fixed exchange rate, free capital movements, and an independent monetary policy.) In China today, the choice is between:

1. Zero Covid;

2. Economic growth around 5%;

3. Social stability.

In 2020 and 2022, China opted for 1 plus 3, sacrificing option 2, growth, which the International Monetary Fund estimated at 2.2% in the first year of pandemic and 3.2% this year as a result of Covid restrictions. But option 1 now appears incompatible with option 3 as well. In theory, Xi might opt for 1 plus 2 either by crushing real wages through a big devaluation or by following the western example and handing money to households, encouraging them to spend it online. But lower wages would guarantee instability while a strategy of “stimulus checks” and consuming from home would mean ending the Party’s campaign against the country’s big tech companies. The logical solution must be to abandon zero Covid and combine options 2 and 3.

However, if this is what the Party has decided, it is hugely risky. China has 264 million over-60s and 36 million over-80s, according to government statistics. According to the National Health Commission, 32 million over-60s (12%) and 8 million over-80s (22%) have never been vaccinated at all. Tens of millions of other high-risk individuals got the first two doses but declined to get the booster. Given the low efficacy of Chinese vaccines — and the passage of 18 months since the second doses were given out — this population might as well be unvaccinated. By comparison, 98.5% of over-65s in the United States have had at least one shot of mRNA vaccines that are more effective against severe disease than the inactivated virus vaccines available in China.

Now China seems set to begin another round of vaccinations. CSPC Pharmaceutical’s SYS6006 mRNA vaccine candidate is likely far more effective than existing Chinese vaccines, judging by the impressive antibody responses it produced in middle-aged adults in its Phase 1/2 trial. The company is still awaiting safety data with respect to the elderly population. There are no Phase 3 clinical efficacy data yet. But the Chinese authorities could potentially issue emergency approval and steer the scarce doses to the highest-risk groups. They will also need to overcome anti-vaccine sentiment amongst the elderly population. The CCP may seem omnipotent. It has nevertheless evinced a very Confucian reluctance to force senior citizens to get their shots.

Yet if any Chinese city experiences a big wave of infections before the high-risk population is vaccinated or boosted, hospitals are likely to be overwhelmed, with shortages of beds, healthcare workers, and equipment, not to mention challenges distributing antiviral medications. China is especially short of intensive care unit beds: It has fewer than 5 per 100,000 people. Taiwan has 28; Singapore 12. And a surge seems very likely indeed if the zero-Covid policy really is being relaxed. In November, when local officials enacted 20 minor rule changes issued by the central government, daily reported cases rose 2,000% in the space of a month.

What might happen if a city like Guangzhou loses control of its outbreak before the vaccination issue is resolved? For an answer, look across the border to Hong Kong, where 0.1% of the population died of Covid in a six-week period last March and April. Hong Kong has far more hospital beds and healthcare workers per capita than mainland China, but the system buckled under the pressure. With morgues overflowing, living patients were left in hospital rooms with cadavers.

Western investors who have been itching to deploy capital to China this year are celebrating the apparent abandonment of the zero-Covid policy. They should be careful what they wish for. Assuming that the infection fatality rate in China would be around 0.2% (as in Taiwan’s recent Covid wave), a hasty reopening would imply around 3 million deaths, assuming no immunity, or 1 million, factoring in vaccine uptake rates and conservative assumptions about protection against severe disease. There is, in sum, no easy way out of Xi’s trilemma.

Three years ago, at a conference in Seoul, I bet the Chinese economist Justin Yifu Lin 20,000 yuan that China’s economy — defined as GDP in current US dollars — would not overtake that of America in the next 20 years. That was regarded by most experts as a wildly contrarian bet on my part. But the consensus view overestimated the resilience of the Chinese model.

In my book Civilization: The West and the Rest (2011), I argued that six “killer apps” had set western civilization apart from other civilizations so that, beginning in around 1600, growth and living standards in western Europe and its settler colonies surged ahead. These were:

Since the demise of Mao Zedong, China has belatedly downloaded four of these — 2, 4, 5 and 6 — but not two, namely political competition and the rule of law. My bet has long been that this selective adoption of the western operating system is not sustainable because it leaves far too much power in the hands of the CCP elite. That did not matter so much when China’s leaders were committed to a policy of “opening up.” The trouble began with the rise to power of Xi Jinping.

As Matt Pottinger, Matthew Johnson, and David Feith argue in a new Foreign Affairs article, Xi has set out to restore the mid-20th-century Marxist-Leninist model. His speeches and writings directed at internal Party audiences reveal “a deep fear of subversion, hostility toward the United States, sympathy with Russia, a desire to unify mainland China and Taiwan, and, above all, confidence in the ultimate victory of communism over the capitalist West.”

“Why did the Soviet Union disintegrate? Why did the Soviet Communist Party collapse?” Xi asked in a speech in December 2012. “An important reason was that their ideals and beliefs had been shaken. … It’s a profound lesson for us! … A few people tried to save the Soviet Union. They seized Gorbachev, but within days it was turned around again, because they didn’t have the tools of dictatorship. Nobody was man enough to stand up and resist.”

Central Committee Document No. 9, April 2013, called on the Party to stamp out Western “false ideological trends,” including constitutional democracy, the notion that Western values are universal, the concept of civil society, economic neoliberalism, and journalistic independence. Why? Because “Western anti-China forces” were pointing “the spearhead of Westernization, division, and ‘color revolution’ at our country.”

“Just like Marx, we must struggle for communism our entire lives,” Xi said in a 2018 speech. “A collectivized world is just there, over [the horizon]. Whoever rejects that world will be rejected by the world.” A textbook published by the People’s Liberation Army quotes Xi as saying that “our struggle and contest with Western countries is irreconcilable, so it will inevitably be long, complicated, and sometimes even very sharp.”

The good news is that I think I am going to win my bet with Justin Lin. The bad news is that, faced with an impossible trinity at home, Xi Jinping may seek to salvage the Party’s legitimacy by picking a fight abroad. He would not be the first dictator in history to go down this road in response to the internal contradictions of an authoritarian system.

It would have been a much safer world over the past century if all one-party regimes ended with the “murmuration” of disenchanted crowds. The Soviet Union did (though the revolution of 1991 did not solve the centuries-old problem of Russian imperialism) as did fascist regimes in Spain, Portugal and South Africa. Nazi Germany, fascist Italy, and imperial Japan, by contrast, ended with a mighty bang.

We shall find out much sooner than most people think how tyranny ends in China. As the crowd steers the Party — and the people — toward their fateful rendezvous with Covid-19, the final act in this vast human tragedy begins.

Mike Pence on Leadership and the Future of the Republican Party

Former US Vice President Mike Pence looks back on the events of January 6 2021, his final days in office with President Trump and his…

Thought Leader: Mike Pence

Marc Short on U.S. Investment in Critical Minerals

Why do critical minerals matter now? Marc Short explains how U.S. investment in critical minerals fits into a broader strategy around economic security, manufacturing, and…

Thought Leader: Marc Short

Marc Short on AI Policy and the Government’s Role in Chip Technology Investment

On CNBC, Marc Short breaks down the role of AI policy and how government investment is shaping the future of chip technology. A former Chief…

Thought Leader: Marc Short