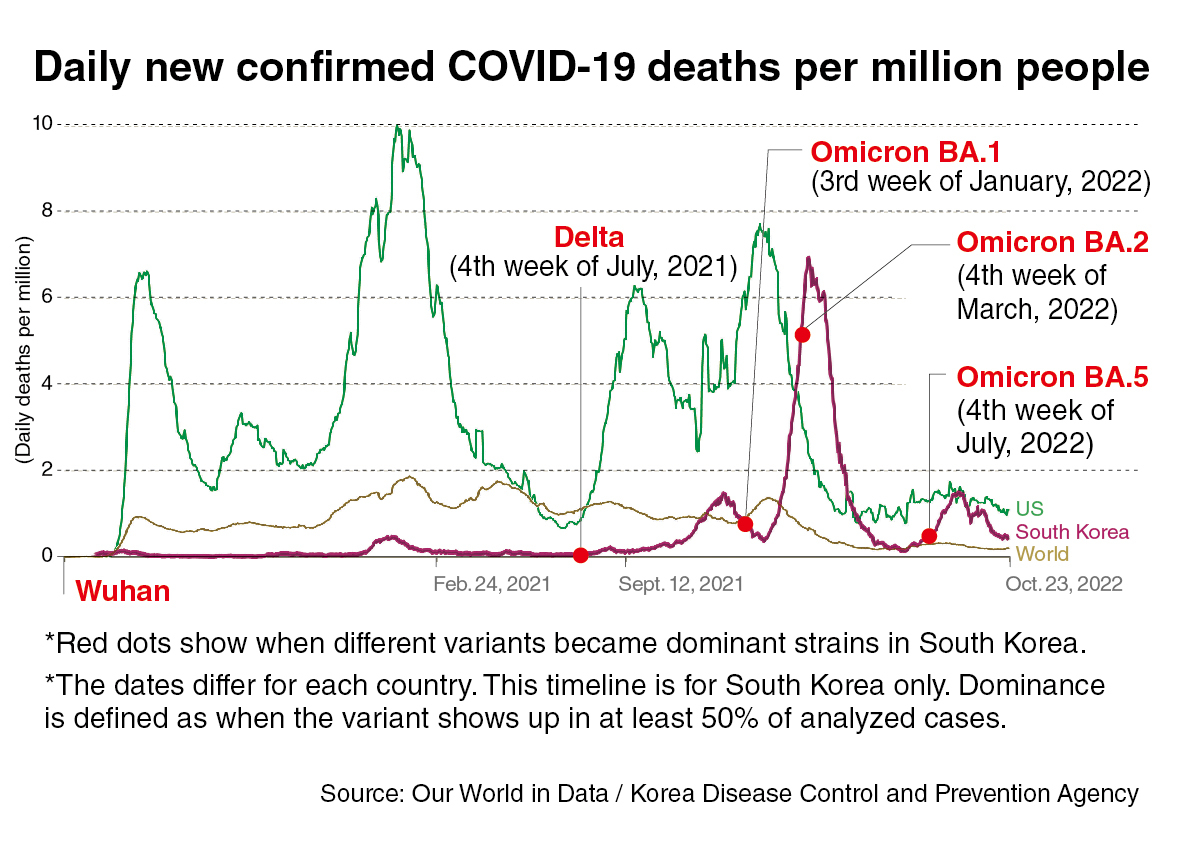

South Korea ended most of its COVID-19 policy responses as omicron hit in January this year. Then it backfired, leading to one of the world’s highest death counts from BA.1 and 2, omicron’s two subvariants that were circulating then.

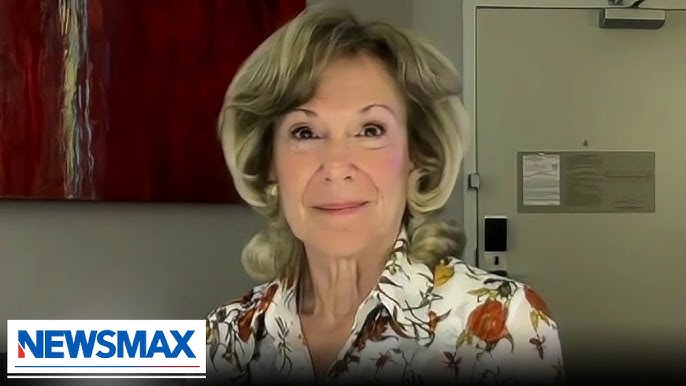

“To me it’s a teaching moment that’s unfortunate that it happened,” said Dr. Deborah Birx, who served as the White House COVID-19 response coordinator.

In an interview with The Korea Herald, Birx pushed back on the rationale given by South Korean authorities for removing government actions under what has been called the omicron response plan — that the virus has gotten milder and more flulike. And that with high vaccination rates, most people, except for those at high risk, could stop being cautious.

With the plan, free universal testing, immediate access to hospital care for the elderly and contact tracing, among other measures, came to an end.

“Viruses in general do evolve that way (to get milder), because they need to replicate and infect the next person so it’s less successful for them to kill the host quickly,” she said. She added, however, that there was no definitive data that shows that the COVID-19 virus has evolved to get milder with omicron.

“What we have is definitive data that our tools have made the outcomes better,” she said. “Our ability to treat people has gotten better. Our knowledge about how to treat them, our clinical care have gotten better.”

The progress made over the years made it difficult to do one-on-one comparisons with earlier variants.

“We’re not comparing apples to apples any longer. So I can’t tell you definitively that either delta or omicron is milder,” she said.

While some have compared omicron with the seasonal flu, Birx said, “I always think that is a complete mistake, to ever imply to the population that this is like flu.”

She said the flu comparison was “extraordinarily dangerous.” The majority of flu cases did not cause long COVID-like symptoms, neurologic late findings, new-onset diabetes, heart attacks or strokes. COVID-19, on the other hand, was causing long-term consequences “in a way we don’t even understand yet.”

The uncertainties surrounding COVID-19’s ability to leave a long-lasting impact, which can happen to even people with mild to moderate disease, made it a risk for young and otherwise healthy people too.

“If you’re a young person 35 or under, your risk of having severe disease, hospitalization and death is low. But it isn’t low to long COVID,” she said. “So it’s not like the flu.”

On the “focused protection” of high-risk people, while the rest return to normal lives, Birx pointed out that the vulnerable lived within the community, interacting with those who are not as at-risk.

“I’m not just talking about people in nursing homes. There are people over 70 who do not live in nursing homes. They live in the community. That’s a huge group. We can’t put that many of the population at risk.”

Another issue with the “let it spread” approach is that it was clear by the end of the first year of the pandemic that natural infection did not lead to long-term protection against another infection, she said. So populationwide exposure was not going to lead to herd immunity. “We know that’s not possible,” she said.

The spike in deaths that South Korea witnessed following the retreat from previous measures highlighted the importance of policy guidance.

“Your bars (of the omicron death graph) would not have been that high, if everyone was tested early and got Paxlovid or therapeutics,” she said.

“You can see the people of South Korea kept the spread extraordinarily contained a long time for nearly two years,” she said, until this year’s turnaround. “And I bet if you ask them, they would say, ‘Well, I thought you (officials) told me I didn’t have to do the mitigation so I stopped doing it.’”

Birx said that if public health decision-makers or politicians want to relax guidelines, they have to be “very clear that the virus is not gone.”

“First do the science and get the data,” she said. “As long as everyone understands the risks involved, and the government does the hard work of empowering people with the knowledge to be able to make their own decisions, and give them the tools, then I think we can have a discussion.”

Last month when US President Joe Biden said the pandemic was over, Birx countered him in a media interview. “Because the pandemic is not over,” she said.

Biden has not been the only leader eager to declare the pandemic over or suggest that the end is near. South Korea’s former President Moon Jae-in said as early as February 2020 that the novel coronavirus outbreak in South Korea was about to end. Then over the two years that followed, he said on many occasions the pandemic’s end was near.

“We have to be honest with ourselves about where we are and not make promises we can’t keep,” Birx said, adding that it was increasingly becoming an unpopular thing to do.

“But no matter who’s in charge, we can’t do pandemic response by polling. You either stick with the science and the data, or you get diluted by polling and perceptions.”

She said COVID-19 is still killing people at a rate that “isn’t acceptable” — around 2,000-3,000 deaths per week in the US for the past few months. Declaring the pandemic is over would send a message that “we’re going to accept a certain level of deaths.”

“If you don’t treat every hospitalization and every death as a programmatic failure, then you don’t fix things in real time,” she said.

“The virus is still a global threat to specific populations. People who have comorbidities or are immunosuppressed or over 65 are valuable members of the community, and we should not trivialize their lives and their contribution to society.”

In South Korea, about 80 percent of all deaths to date have been in people 70 and older.

She said that COVID-19 is “not going to miraculously disappear” but that just meant we “update our tools.”

Birx, who led the HIV/AIDS efforts at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, pointed out that HIV, far from disappearing, has been around for some 40 years.

“HIV — it’s transmitted totally differently — continues to mutate, continues to develop resistance patterns to different drugs, and continues to impact different groups of people,” she said.

And new COVID-19 variants of concern and surges of cases should no longer be a surprise.

“Because it’s the virus’ job, and it’s doing it well,” she said. “We should never be surprised that this new variant came. This is a virus that is very fit to infect humans. It’s obviously mutating away from vaccines, prior infection, immunity and all of our monoclonal antibodies.”

She said the virus will continue to cause surges until there is a vaccine that is durable and protects against infection and reinfection — which won’t be easy.

“When we made the vaccine, we mimicked natural infection. Once it was clear that natural infection did not lead to long-term protection against reinfection, then you knew the vaccine wouldn’t either,” she said.

“If we want to prevent transmission and create herd immunity, then we need to work on vaccines that do better than natural infection. That’s hard to do.”

Birx said that in the meantime, the answer was more availability of testing, therapeutics, vaccination and boosting while at the same time recognizing that protection against reinfection wanes. “And then you could accidentally infect someone,” she said.

She said that knowledge at the community level is “what stops pandemics,” and that it was possible for communities to live successfully with the virus.

“I think your data show so clearly that the people of South Korea knew what to do,” she said, adding, the members of the public should be given credit for “doing what is right.”

“They just need to have their officials reinforce when they have to do those things that they know are so successful and working.”

When another surge arrives, people “should do that once again,” she said.

“Look at how short that (surge) was. You’re asking people to modify their behavior for six to eight weeks to protect their family members, and people would do that.”

She said that with COVID-19, we are “still failing on a series of issues.”

“We still don’t have a clear therapeutic plan for people who have long COVID. We don’t know how much the vaccines protect against long COVID. We should know that by now,” she said.

“I think we’re not approaching with the same rigorous science and data to be able to say this is where we are in the pandemic, this is why reinfection is occurring.”

Thanks to therapeutics and vaccines, the key metrics on hospitalizations and deaths have improved.

“We’re better, but we’re not there yet,” she said. “I don’t like it when people give up before the job is done.”