Time to end secret data laboratories—starting with the CDC

The American people are waking up to the fact that too many public health leaders have not always been straight with them. Despite housing treasure…

Thought Leader: Marty Makary

At a time when the federal government is reducing funding for biomedical research at the National Institutes of Health—thereby fraying the partnership between government and academia that made US biomedicine the envy of the world—and as large-scale staff reductions at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are hindering drug development and delaying some approvals, the US’s standing as the globe’s foremost hub for biomedical innovation faces an increasingly serious challenge from China.1,2 Yet, even as US policymakers fixate on geopolitical rivalry with China, remarkably little attention is being paid to the risk that the US might surrender its strategic edge in biomedicine, a loss every bit as damaging as falling behind in semiconductors, rare earth minerals, or military hardware. If the US is serious about staying at the forefront of biomedicine, fresh approaches that reduce discovery hurdles and enable a wider spectrum of researchers, especially those in academic laboratories, are needed to navigate the complexities of drug development.

A robust biomedical ecosystem provides the US with strategic independence, reducing its vulnerability to geopolitical adversaries who might exploit crises by withholding critical technologies. By sustaining leadership in biomedical innovation, the US can also set global regulatory norms and ethical benchmarks in biotechnology, limiting the ability of rival powers to advance agendas incompatible with US interests. In the long run, maintaining a decisive edge in these areas ensures US autonomy, preventing other nations from controlling the technologies that shape the health and security of US citizens in such key goals of reducing the burden of chronic disease and addressing unmet medical needs.

For years, US drug companies had outsourced parts of their early pharmacology work to China, where local firms produced compounds according to designs provided by their Western partners. The compounds were then tested in US-based clinical trials, a global division of labor that was efficient, if uneven. Now that Chinese firms have mastered medicinal chemistry along with the underlying science and sophisticated manufacturing processes needed to develop advanced biologics, they can often produce drug candidates more quickly and cheaply than their US counterparts. Instead of merely executing Western blueprints, the Chinese drugmakers create proprietary compounds, notably in cutting-edge areas such as antibody drugs and cell therapies.

As US capital increasingly flows toward the more economical Chinese assets, this process might hollow out the US ecosystems that underpin early-stage science. Reconstituting the robust scientific infrastructure that once fueled US biotechnological breakthroughs could become exceedingly difficult. We ought to strengthen the foundations of the US’s biomedical enterprise by implementing measures that reduce the cost and complexity of initial drug development.

This strategy could help keep our entire discovery engine more cost-competitive with Chinese biotechnology firms, which are increasingly gaining the advantage. Their edge lies in a nimble ability to shuttle promising compounds more quickly through early preclinical and phase 1 clinical trials, by testing what works, discarding what does not, and sharpening their focus through real-time data. If the US can lower the regulatory barriers to preclinical and phase 1 clinical testing, we can also expand more of these experiments into the hands of nimble academic laboratories, thereby broadening, rather than narrowing, the scope and productivity of US biomedical research.

Currently, one major hurdle in the US is the FDA’s requirements for exhaustive, costly animal studies that probe obscure aspects of drug effects, sometimes far removed from their actual therapeutic use. Over the years, the toxicology component of the FDA’s drug-review process has operated with an increasing degree of independence from the agency’s clinical review divisions responsible for evaluating new medications. Drug developers often find themselves enmeshed in prolonged discussions with toxicologists about how animal studies should be conducted, followed by time spent performing those required studies. Simplifying this process could enable the US to support a larger base of early-stage drug discovery, including work conducted by academic laboratories, and ultimately bring life-changing therapies to patients more efficiently.

The FDA could leverage vast troves of existing drug data to create a more phased approach to preclinical testing. Instead of one-size-fits-all requirements, initial animal studies could be tailored to each drug program, based on the novelty of the molecule being examined and an informed estimate of its potential risks. Artificial intelligence could play a role by mining databases, extrapolating from known drug profiles, and predicting safety issues before extensive testing begins. These tools could be particularly valuable for streamlining preclinical requirements.

For example, despite the abundance of data from previous animal studies with existing drugs, we remain surprisingly ineffective at using it to refine artificial intelligence models that could offer some predictive value. A better grasp of how to translate these findings could allow us to draw more-precise conclusions from fewer animal experiments, ultimately reducing the scale of animal testing required. By using these tools, regulators would be able to better identify which drugs are most likely to reveal novel risks and thereby merit closer scrutiny in preclinical studies. For drugs structurally like already-approved compounds, some preclinical studies may be deferred entirely. If regulators could lower the cost of preclinical testing for compounds unlikely to uncover novel risks in animal models, more academic laboratories would be enabled to carry their discoveries into phase 1 clinical trials. This shift would enable academic institutions to capture a larger share of the value from their inventions and widen the circle of participants in early drug development.

The FDA could also develop standardized templates for enrolling patients and investigators in phase 1 clinical trials, explicitly aimed at lowering the complexity for academic institutions eager to conduct these early-stage studies. This would include standardized digital enrollment forms and preapproved consent documents that streamline patient recruitment and cut paperwork.

Widening the use of platform trials could also expand more opportunities for academic laboratories.3 Platform trials are an innovative type of clinical trial design that simultaneously evaluates multiple treatments for a disease within a single, ongoing trial framework. Unlike traditional clinical trials, which test a single drug or intervention separately, platform trials use a standardized master protocol that enrolls patients with a particular disorder, allowing new treatments to be added or removed seamlessly over time. Such approaches speed the assessment of multiple interventions, enabling quicker identification of effective therapies. Currently, these trial designs are typically limited to the conduct of late-stage clinical studies. By adapting these approaches to earlier, phase 1 trials, more academic institutions could become sponsors of platform studies, enabling them to assess promising compounds at the earliest stages of development.

Finally, for the later stage clinical trials, when new drugs are tested in larger groups of patients, the mature regulatory system in the US remains a clear advantage, and we should continue investing in its strength. Showing that a drug is safe and effective through rigorous clinical studies, conducted under the FDA’s oversight, gives the US a competitive edge that China cannot match. While Chinese regulators allow new compounds to advance into early-stage clinical trials with greater ease, the data from their later-stage, human trials are still viewed skeptically by US regulators and drug companies.4 The FDA’s robust system for clinical testing remains a distinctive edge, and we should seek to strengthen the successes of this model.

Recent efforts to chip away at institutions like the FDA and National Institutes of Health have undercut some of the very offices responsible for driving these kinds of policy innovations, making thoughtful reform harder to achieve. Both agencies could benefit from changes designed to boost efficiency and encourage novelty. However, recent cuts were less like targeted and strategic restructuring and more like a broad stroke to shrink the federal enterprise wholesale. Such changes will not leave these institutions more competitive—they could simply leave the entire enterprise weaker at a critical juncture in its history. If we fail to halt the drift of biomedical discovery toward China, we risk ceding a strategic technological advantage that may prove all but impossible to win back.

Dr. Scott Gottlieb, former Commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, is one of today’s most trusted voices in healthcare policy and pharmaceutical innovation. With deep experience at the highest levels of public health leadership, Dr. Gottlieb offers expert analysis on the evolving landscape of healthcare regulation, drug development, biopharma trends, and global market forces such as tariffs and supply chain disruption. A physician, policymaker, and thought leader, he regularly advises organizations navigating complex health and economic challenges. His insights are essential for anyone seeking clarity at the intersection of science, policy, and innovation. For speaking inquiries, contact WWSG.

Time to end secret data laboratories—starting with the CDC

The American people are waking up to the fact that too many public health leaders have not always been straight with them. Despite housing treasure…

Thought Leader: Marty Makary

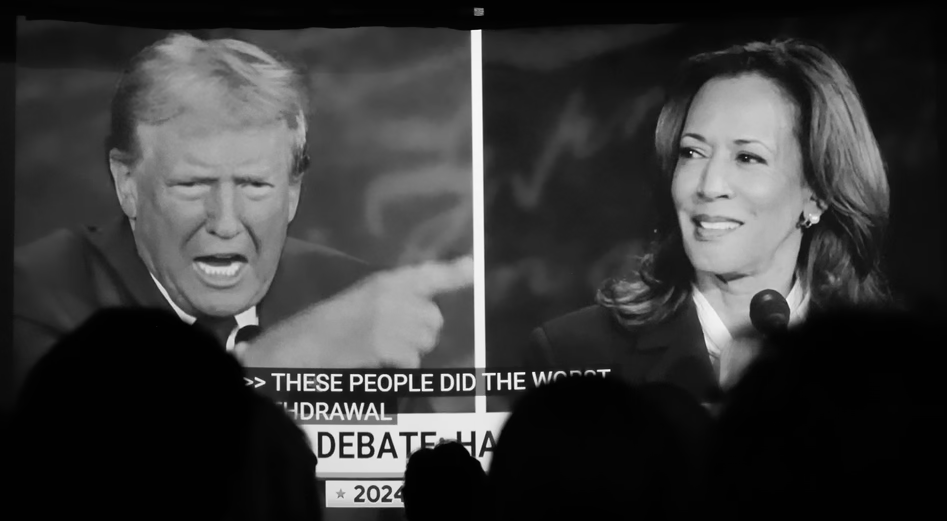

David Frum: How Harris Roped a Dope

This piece is by WWSG exclusive thought leader, David Frum. Vice President Kamala Harris walked onto the ABC News debate stage with a mission: trigger…

Thought Leader: David Frum

Michael Baker: Ukraine’s Faltering Front, Polish Sabotage Foiled, & Trump vs. Kamala

In this episode of The President’s Daily Brief with Mike Baker: We examine Russia’s ongoing push in eastern Ukraine. While Ukrainian forces continue their offensive…

Thought Leader: Mike Baker