Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson review

(Evening Standard) – From plagues and volcanic eruptions to the current Covid pandemic, mankind has always been faced with catastrophes.

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

This is what the auto industry wants people to see: sparkling factories turning reclaimed lead into batteries for Ford, Toyota, GM and the rest.

But in Africa’s lead recycling capital, reality looks very different.

Factories are poisoning people. We know because we tested them.

This dirty lead goes into American cars.

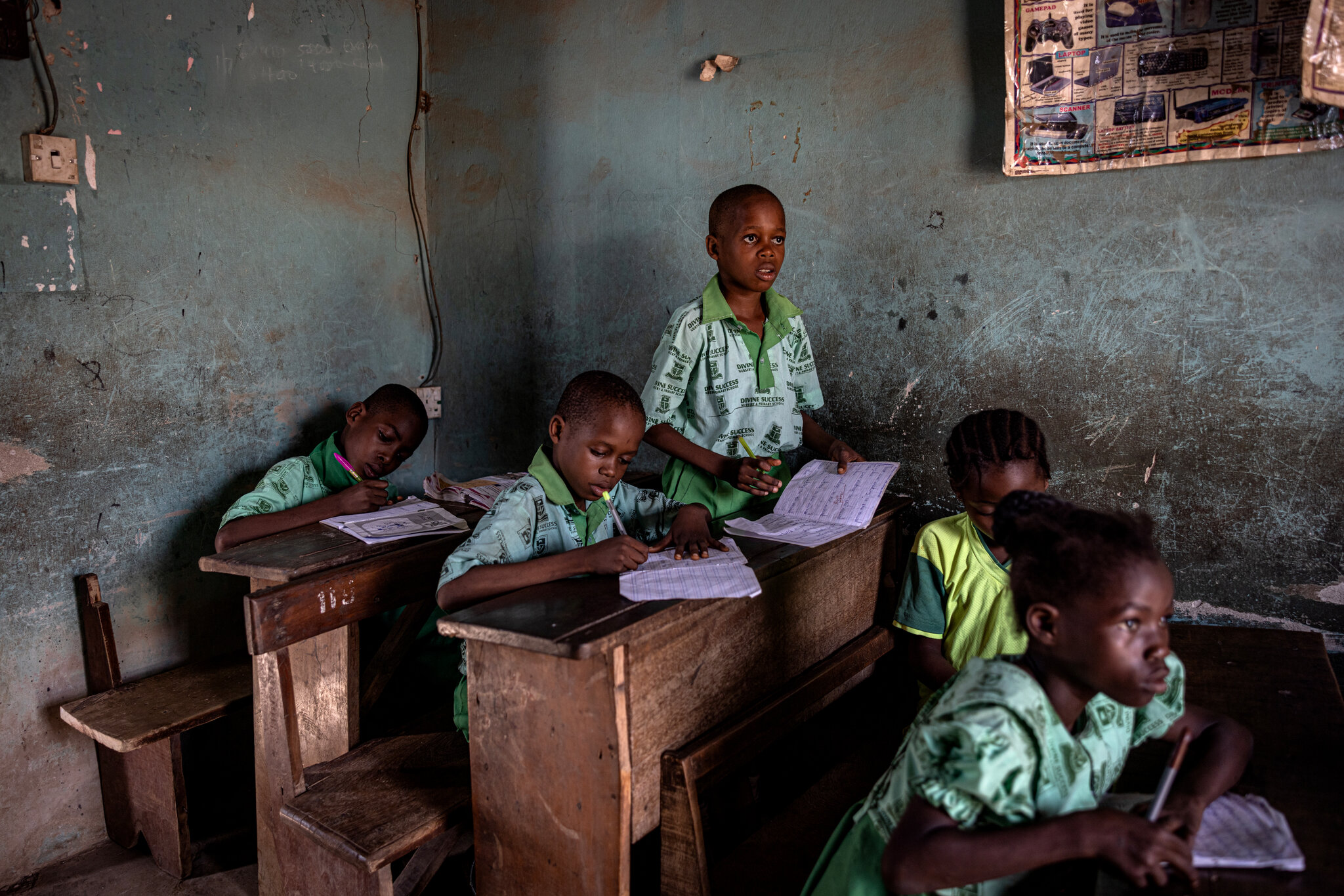

POISONOUS DUST falls from the sky over the town of Ogijo, near Lagos, Nigeria. It coats kitchen floors, vegetable gardens, churchyards and schoolyards.

The toxic soot billows from crude factories that recycle lead for American companies.

With every breath, people inhale invisible lead particles and absorb them into their bloodstream. The metal seeps into their brains, wreaking havoc on their nervous systems. It damages livers and kidneys. Toddlers ingest the dust by crawling across floors, playgrounds and backyards, then putting their hands in their mouths.

Lead is an essential element in car batteries. But mining and processing it is expensive. So companies have turned to recycling as a cheaper, seemingly sustainable source of this hazardous metal.

As the United States tightened regulations on lead processing to protect Americans over the past three decades, finding domestic lead became a challenge. So the auto industry looked overseas to supplement its supply. In doing so, car and battery manufacturers pushed the health consequences of lead recycling onto countries where enforcement is lax, testing is rare and workers are desperate for jobs.

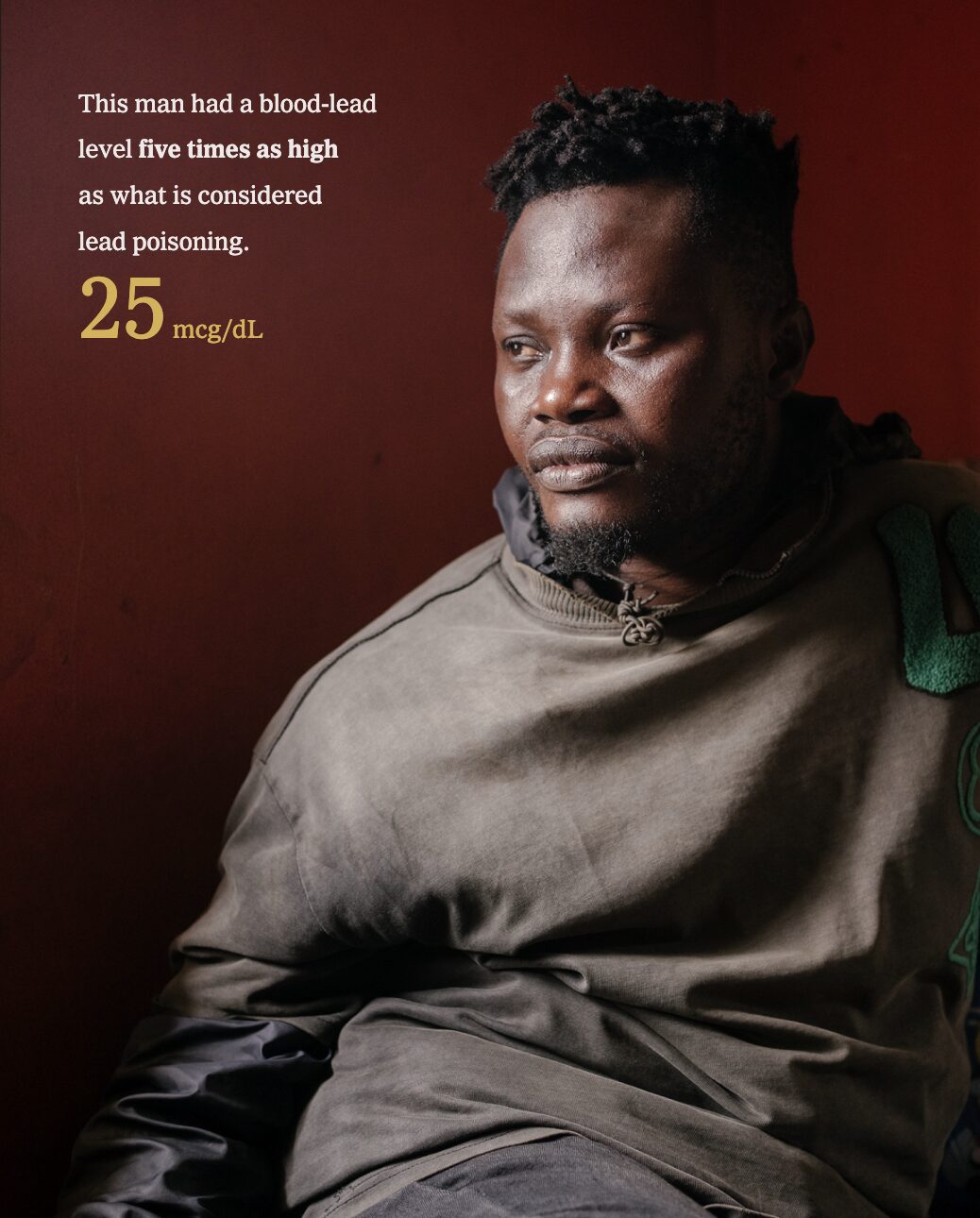

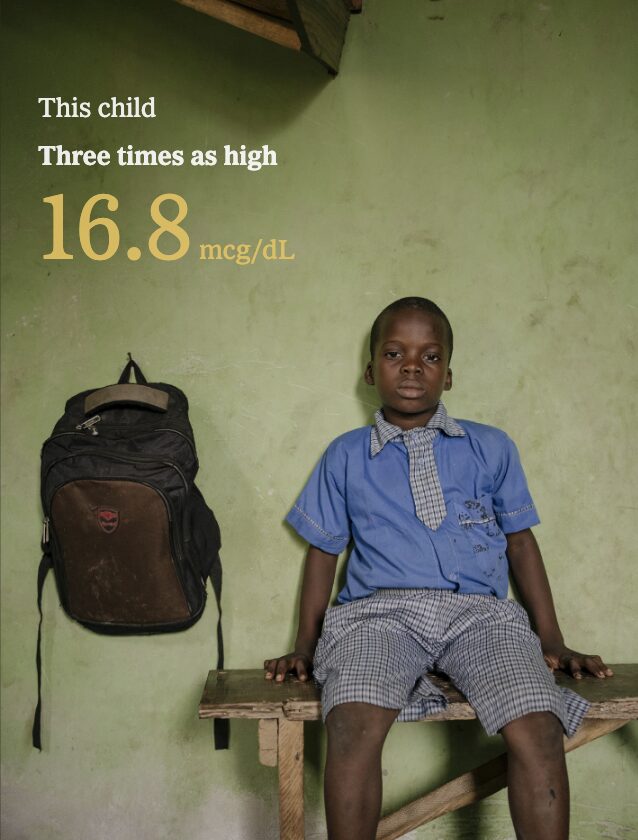

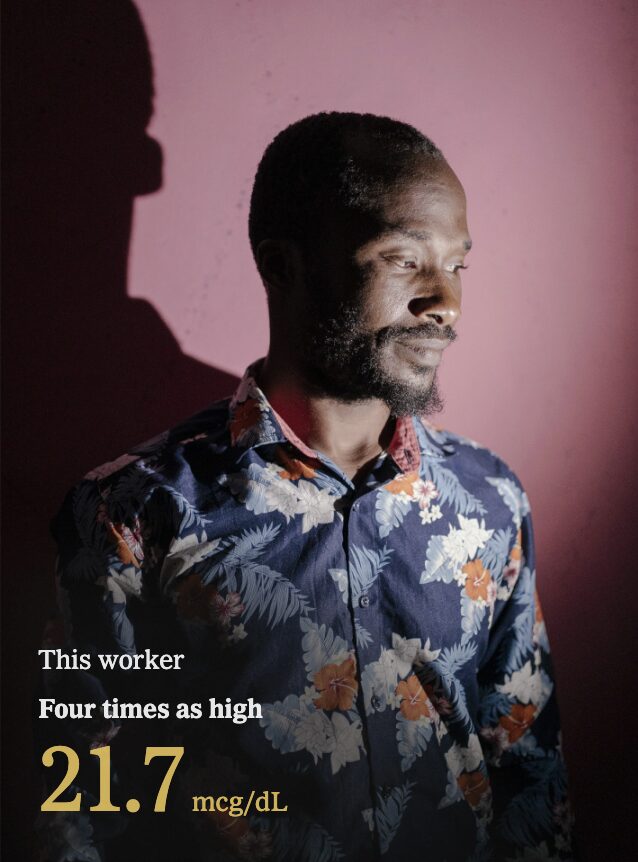

Seventy people living near and working in factories around Ogijo volunteered to have their blood tested by The New York Times and The Examination, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates global health. Seven out of 10 had harmful levels of lead. Every worker had been poisoned.

More than half the children tested in Ogijo had levels that could cause lifelong brain damage.

Dust and soil samples showed lead levels up to 186 times as high as what is generally recognized as hazardous. More than 20,000 people live within a mile of Ogijo’s factories. Experts say the test results indicate that many of them are probably being poisoned.

Lead poisoning worldwide is estimated to cause far more deaths each year than malaria and H.I.V./AIDS combined. It causes seizures, strokes, blindness and lifelong intellectual disabilities. The World Health Organization makes clear that no level of lead in the body is safe.

The poisoning of Ogijo is representative of a preventable public health disaster unfolding in communities across Africa. One factory’s lead soot falls onto tomato and pineapple farms near a village in Togo. Another factory has contaminated a soccer field in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s largest city. In Ghana, a recycler melts lead next door to a family’s chicken coop.

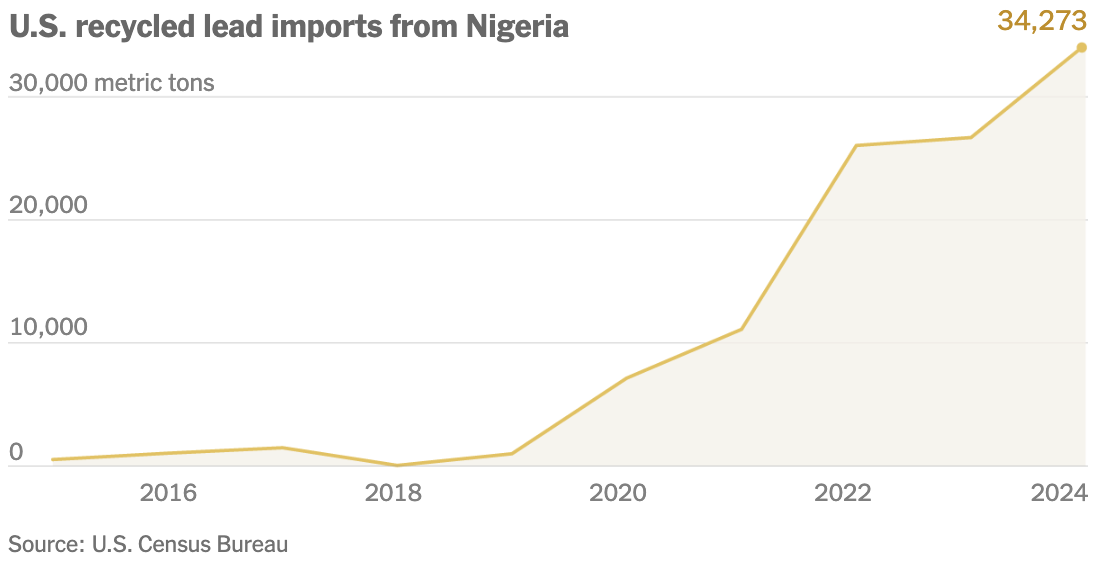

Factories in and around Ogijo recycle more lead than anywhere else in Africa. The United States imported enough lead from Nigeria alone last year to make millions of batteries. Manufacturers that use Nigerian lead make batteries for major carmakers and retailers such as Amazon, Lowe’s and Walmart.

The auto industry touts battery recycling as an environmental success story. Lead from old batteries, when recycled cleanly and safely, can be melted down and reused again and again with minimal pollution.

But companies have rejected proposals to use only lead that is certified as safely produced. Automakers have excluded lead from their environmental policies.

Battery makers rely on the assurances of trading companies that lead is recycled cleanly. These intermediaries rely on perfunctory audits that make recommendations, not demands.

The industry, in effect, built a global supply system in which everyone involved can say someone else is responsible for oversight.

Nigeria, the economic engine of West Africa, is among the fastest-growing sources of recycled lead for American companies.

Ogijo and the communities nearby make up the heart of the industry, home to at least seven lead recyclers. Two factories are near boarding schools. Another faces a seminary. Others are surrounded by homes, hotels and restaurants.

Among the largest and dirtiest lead recyclers in Ogijo is True Metals. It has supplied lead to factories that make batteries for Ford, General Motors, Tesla and other automakers, records show. True Metals did not respond to questions about its practices or the lead test results.

Four years ago, Oluwabukola Bakare was pregnant with her fifth child when she moved into a home in Ogijo within sight of a battery recycling factory.

The smoke seeped through the windows at night, making her family cough and leaving a black powder on their floor and food.

“In the morning, when we looked outside, the ground seemed to be covered in charcoal,” Ms. Bakare said.

Testing revealed that her 5-year-old son, Samuel, had a blood-lead level of 15 micrograms per deciliter, three times the level at which the World Health Organization recommends action. His 8-year-old brother, Israel, tested even higher.

Ms. Bakare, 44, has worked inside battery recycling factories for years, cleaning toilets and sinks. Her test showed she had a lead level of 31.1 micrograms per deciliter, which is associated with complications including miscarriages and preterm birth.

Now she wonders whether the smoke contributed to her son’s premature birth at seven months.

To understand the extent of Ogijo’s contamination, consider what happened more than a decade ago in Vernon, Calif., the site of one of the worst cases of lead pollution in modern American history. Soil testing around a recycling plant revealed high lead levels, including at a nearby preschool. Officials called the area an environmental disaster. The factory closed. The cleanup continues today.

Soil at the California preschool contained lead at 95 parts per million.

In Ogijo, soil at one school had more than 1,900 parts per million.

All this is avoidable. Lead batteries can indeed be recycled as cleanly as advertised. In Europe, experts say, some recycling factories are spotless. But that requires millions of dollars in technology.

Roger Miksad, the president of Battery Council International, an industry group, said that American manufacturers got 85 percent of their lead from recyclers in North America, where regulations are generally strict.

As for the growing amount from overseas, he said his group condemns unacceptable practices and advises lead recyclers on how to improve conditions.

“But at the end of the day,” Mr. Miksad said, “it’s up to regional and local governments and regulators to enforce the laws in their countries.”

Most major car companies did not address the Times and Examination findings about tainted lead from Nigeria. Volkswagen and BMW said they would look into it. Subaru said it did not use recycled lead from anywhere in Africa.

The test results, though, affirm years of research about the industry’s toll in Africa.

A 2010 study found widespread lead poisoning among workers at a recycler called Success Africa in Ghana. One employee’s lead level was so high that doctors were surprised he was alive. (Success Africa did not respond to requests for comment).

Yet the factory stayed open and in recent years has sold lead to a battery supplier for BMW, Volkswagen and Volvo. The Ghanaian Health Ministry recently found that 87 percent of children living near Success Africa had lead poisoning.

Nearly all of the lead recycled in Africa is used to make electrode plates for batteries. Because lead from various sources is combined during manufacturing, it is impossible for consumers to know the origin of the lead in their car batteries.

Nigerian officials are ill equipped to monitor any of this. The government is battling an armed insurgency and endemic corruption and struggles to provide basic health services, even for urgent concerns like malaria. Power is dispersed among federal, state and local authorities. Local monarchs hold largely ceremonial power.

In Ogijo, recycling is a dirty, dangerous process. It begins with a dead battery. There are plenty; the United States sends tens of thousands of secondhand cars to Nigeria each year.

Then, workers known as breakers prepare the batteries to be recycled. They use machetes to hack into the plastic casings and drain the acid.

These breakers work for Goodluck Ejika, 43. “Today,” he said, “True Metals has called me five times.” Mr. Ejika handles hundreds of batteries every day.

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson review

(Evening Standard) – From plagues and volcanic eruptions to the current Covid pandemic, mankind has always been faced with catastrophes.

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

Time to end secret data laboratories—starting with the CDC

The American people are waking up to the fact that too many public health leaders have not always been straight with them. Despite housing treasure…

Thought Leader: Marty Makary

Scott Gottlieb: How well can AI chatbots mimic doctors in a treatment setting?

This is an Op-ed by WWSG exclusive thought leader, Dr. Scott Gottlieb. Many consumers and medical providers are turning to chatbots, powered by large language…

Thought Leader: Scott Gottlieb