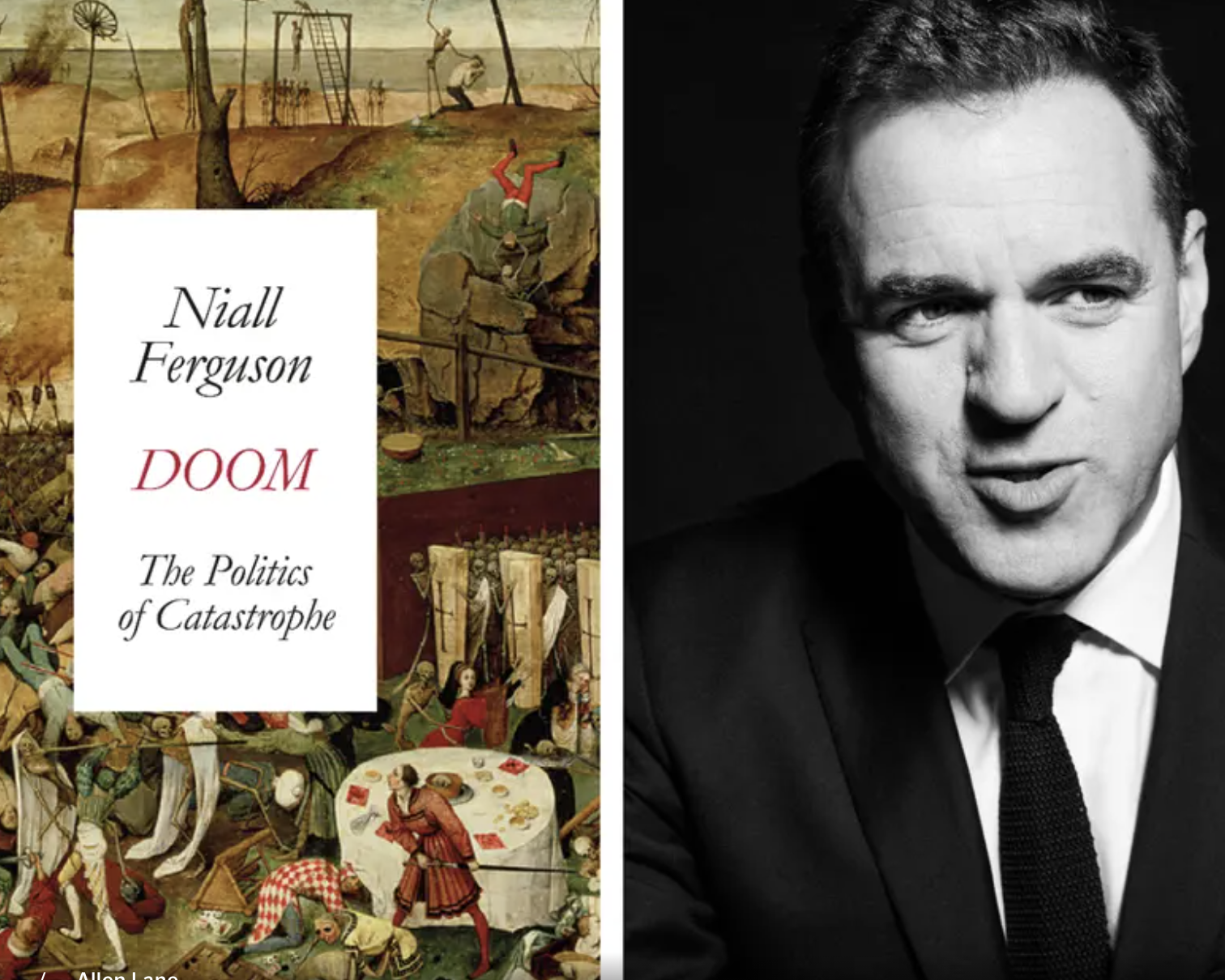

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson review

(Evening Standard) – From plagues and volcanic eruptions to the current Covid pandemic, mankind has always been faced with catastrophes.

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

The 1920s were Roaring, the Sixties were Swinging, and the Nineties were Cool (as in ‘Cool Britannia’), but what will historians call the 2020s?

As we pass the halfway mark, it’s a bit too soon to say for sure how this decade will be remembered. But — unless things drastically change in the country we used to call Great Britain — it’s not likely to be fondly. How about the Snoring Twenties? The Boring Twenties? Maybe the Lowering Twenties, as it’s hard to believe we can sink much lower.

The decade started with a global pandemic that prompted the misery of lockdowns, the social and economic costs of which almost certainly exceeded the public health benefits.

We were then hit with a bout of inflation, two bloody wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, a surge of immigration that I don’t remember anyone voting for, and one of the most anticlimactic changes of government in British history. Oh, and it’s also shaping up to be the wettest decade of my lifetime, starting with 2020, the fourth-wettest year since 1862. The Pouring Twenties, anyone?

In the worst-case scenario, this is shaping up to be a cross between the 1930s and the 1970s — two of the unhappiest decades of the past century.

In economic terms, we remember the Thirties as a time of Depression and the Seventies as a time of stagflation. I don’t think we’ll see such extremes of falling or rising prices. But in social, cultural, political and geopolitical terms, there are some worrying resemblances.

If Sir Keir Starmer is wondering why his new government’s honeymoon has been so painfully short – why his net approval rating collapsed from +19 per cent to -32 per cent in just five months – he can console himself that it’s as much the country’s circumstances as his own missteps.

Britain’s prospects are as grim today as they were bright when Tony Blair came to power with a similar Commons majority in 1997.

True, Starmer is better off than his Labour predecessor Ramsay Macdonald, who became prime minister in the middle of 1929, on the eve of the Great Depression.

Within just a few months, Wall Street crashed and the biggest economy in the world – the United States – went into a death spiral that caused prices and output to fall by a third. The shock spread throughout the world. Global trade and production plunged.

The British economy fared somewhat better than the American, but the Thirties were still bleak here. The unemployment rate peaked at 15 per cent in 1932 and did not fall below 10 per cent until 1936.

In vain did the iconoclastic economist John Maynard Keynes argue that the government could offset the collapse of private demand by public borrowing and investment. Not until the National Government of Neville Chamberlain belatedly began to rearm was there a sustained economic recovery — and that was just the prelude to another world war.

The 1970s were a kind of mirror-image crisis — the result of too much Keynesianism, rather than too little. Successive governments had used public borrowing and loose monetary policy to try to maintain full employment.

The result was stagflation: double-digit inflation (23 per cent at the peak) and lengthening dole queues. Growth slumped. So did national morale — except among over-mighty trade union leaders.

The problem for Britain today is that the previous government (not to mention the Bank of England) repeated a number of the mistakes that led to Seventies stagflation. Inflation jumped to double digits (11 per cent) in 2022. Taxes went up, but so did debt because public spending went even higher. Indeed, taxes as a share of GDP are now at a higher level than in the Seventies, and on track to match their peak in 1948.

Public debt this year is now above 98 per cent of GDP, three times what it was 20 years ago. And economic output has flatlined since Labour took over in July. The International Monetary Fund forecasts that growth will remain below 2 per cent for the remainder of the decade.

A country has a serious problem when its growth rate is below the interest rate on the national debt. That is the real ‘black hole’ that Labour inherited from the Tories. It will not be filled by making generous pay deals with the public sector unions.

As in the 1930s and the 1970s, Britain does not face its economic problems in isolation. They are part of a wider global picture of slowing growth as the sugar rush of pandemic-induced stimulus finally ends.

Europe is in a state of stagnation, the once mighty German engine of growth sputtering feebly. The Bundesbank expects just 0.2 per cent growth next year.

Under Joe Biden, the US economy has run hot. Donald Trump’s re-election on November 5 was in large measure a vote against the inflationary consequences of ‘Bidenomics’. Trump’s nominee for Treasury Secretary, Scott Bessent, has pledged to achieve the Three Threes: 3 per cent growth, cutting the budget deficit to 3 per cent of GDP and boosting oil production by 3million barrels a day. I wish him the best of luck.

Meanwhile, despite repeated attempts at government stimulus, the second-largest economy in the world — China — is also slowing, dragged down by deflation in the property sector and overcapacity in the manufacturing sector.

In short, the 2020s won’t be as deflationary as the 1930s nor as inflationary as the 1970s, but we are still likely to experience low growth. And this decade will be especially tough for Britain, which has the lowest investment rate of any G7 country (17 per cent of GDP; the rest are all above 20), and an exceptionally high reliance on imported energy (up to 40 per cent of its total supply).

As a devastating report by policy wonks Ben Southwood, Samuel Hughes and Sam Bowman shows, Britain is paying the price of two decades of under-investment in housing, energy and transport.

Stagnation won’t manifest itself in the unemployment we saw in the 20th century, however, because in most developed countries populations are ageing and there are even shortages of some kinds of labour — especially in Britain, where the total number of people claiming benefits because of long-term ill-health exceeds 3 million.

That was partly why the post-pandemic recovery produced a surge of immigration. Since 2016, gross immigration has totalled just under 7.4 million. The foreign-born share of the total population of England and Wales is now one fifth.

Yet history warns us that, when tough economic times strike multi-ethnic societies, the result is often conflict. We had a foretaste of what may lie ahead over the summer, in the riots that followed the killings in Southport.

We like to tell ourselves Britain will never be a place where a far-Right party could make the kind of political gains we have seen in the Netherlands, France, and Germany. And it is true Reform UK attracted less support in the July 4 general election than, say, Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in the recent German state elections.

Yet polls of voting intentions now put Nigel Farage’s party alarmingly close to the Tories. Reform is hardly extremist, but the existence of a party to the Right of the Tories divides the conservative vote and raises the probability of a second Labour term.

In the 1930s, and to a lesser extent in the 1970s, economic turbulence fanned the flames of radical nationalism as well as racism. Faced with hardship, people have a craving for belonging, as well as a desire to blame their troubles on outsiders. ‘Germany to the Germans, foreigners out!’ is a slogan favoured by young supporters of the AfD. Similar slogans could gain traction in England, too.

The rhetoric of populism and nationalism has a historic tendency to spill over into violence – not just riots, but sometimes civil war or even full-blown war, Niall Ferguson writes

The problem is that the rhetoric of populism and nationalism has a historic tendency to spill over into violence — not just riots, but sometimes civil war and even full-blown war between states. This is one of the central lessons of the 20th century, an issue I addressed nearly two decades ago in The War Of The World: History’s Age Of Hatred (Penguin).

Why was there so much violence in the 20th century? And why was it so heavily concentrated in time — the 1910s and the 1940s were the deadliest decades — and in space, with a huge proportion of organised lethal violence happening in the terrible triangle of territory between the Baltic Sea, the Balkans and the Black Sea?

The answer is that violence was most likely to occur when economic volatility struck, and where empires were in decline, leaving multi-ethnic societies without robust political institutions.

That is why it is not so surprising war is once again raging in Ukraine, a country perhaps more afflicted by organised violence in the past century than any other.

Russia and Eastern Europe suffered extraordinary economic instability after the collapse of Communism. The disintegration of the Soviet Union was a classic case of imperial decline and fall. But the societies it left in its wake were not well-equipped to make the most of the new opportunities of individual freedom, free markets and democracy.

After Russia was battered by inflation and inequality in the 1990s, there gradually emerged a new Muscovite fascism under Vladimir Putin. It was obvious ten years ago he was ready to use military force to prevent Ukraine from establishing itself as a stable and prosperous democracy.

Yet in 2014 the West responded feebly to his annexation of Crimea and creation of puppet states in parts of the Donbas. And in 2021 we wholly failed to deter Putin from a full-scale invasion.

A similar observation could be made about the Middle East, plagued by violence and instability for more than a century. Today, no one is in charge in the region.

Certainly not doddering, forgotten Joe Biden. Not Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, whose grand designs to modernise his kingdom increasingly recall the Shah of Iran. And not the malignant theocracy that replaced the Shah in 1979, whose terrorist proxies have wreaked havoc from the tunnels of the Gaza Strip to the bunkers of the Lebanese border.

Only the Machiavellian Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu is ending 2024 in a stronger position than a year ago, having crushed Hamas, eviscerated Hezbollah and seized the opportunity presented by the downfall of Bashar al-Assad in Syria earlier this month. But even he must worry about the ambitions of Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

The question that remains to be answered is whether China’s Xi Jinping will take advantage of Western weakness to ignite a third wildfire in the global forest, Niall Ferguson writes

The question that remains to be answered is whether China will take advantage of Western weakness to ignite a third wildfire in the global forest, either by blockading Taiwan or by picking a fight with the Philippines.

It is certainly arming itself — and stockpiling raw materials — as if it intends a showdown. According to William Burns, the director of the CIA, president Xi Jinping has told his military leaders to be ready for war by 2027.

Through overuse, parallels with the 1930s have lost much of their power. When George W. Bush referred to Iran, Iraq and North Korea as an ‘Axis of Evil’ in 2002, no such thing existed.

Yet today we do confront a genuine Axis. China, Russia, Iran and North Korea are all now openly cooperating to support Russia’s war effort in Ukraine.

In September, as I returned to England from an angry Kyiv and an anxious Vilnius (the Lithuanian capital), I contemplated a world that was all too familiar.

For decades, Britain and its European neighbours neglected their armed services, squandering the post-Cold-War ‘peace dividend’. Even today, it is maddeningly difficult to persuade German ministers that they need to get serious about rearmament.

And even with Hamas still holding hostages in Gaza, it seems impossible to convince most Labour MPs — not to mention members of the Oxford Union — that the problem we need to worry about is Islamist terrorism, not Islamophobia, much less Israeli ‘settler-colonialism’.

And even today, as the Axis of Ill Will adds to its nuclear arsenal, it is considered the height of bad taste to suggest World War III is a more imminent threat to humanity than climate change.

I wrote The War Of The World in the hope we could learn from history how to avoid a Third World War. As this decade passes the halfway mark, I can only hope we won’t end up calling it the Thermonuclear Twenties.

Sir Niall Ferguson is Milbank Family Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford, and a visiting professor at the London School of Economics. He is the author of 16 books and is currently completing his biography of Henry Kissinger.

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson review

(Evening Standard) – From plagues and volcanic eruptions to the current Covid pandemic, mankind has always been faced with catastrophes.

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

Time to end secret data laboratories—starting with the CDC

The American people are waking up to the fact that too many public health leaders have not always been straight with them. Despite housing treasure…

Thought Leader: Marty Makary

Feigenbaum: How China Wants High-Tech To Power Its Economy To The Top

Written by WWSG exclusive thought leader, Evan Feigenbaum. In mid-July, China concluded a pivotal economic strategy meeting, where it quadrupled down on technology as the…

Thought Leader: Evan Feigenbaum