Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

In March 2020, at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, the U.S. went into lockdown. Four years later, Covid has receded into the background of our lives. As is typical after serious epidemics, people are now seeking out pleasures they had to forego. Domestic air travel has been above prepandemic levels since last spring. In 2023, LiveNation sold a total of 620 million tickets to concerts and events, its biggest year ever. Data from WHOOP, a wearable fitness tracker, shows that the million users of the device have been dancing much more.

Reckless behavior, which often accompanies people’s sense of liberation once a calamity has passed, is also increasing. Americans gambled a record $66.5 billion in 2023. Compared with 2019, there has been an 18% increase in fatal accidents involving alcohol and a 17% increase in those involving speeding. Over 500 Americans are dying every day from alcohol-related deaths, a 30% increase. Sexually transmitted diseases are rising across the nation, too.

But while we may be done with Covid, it’s not done with us. Over 1.2 million of our fellow Americans have died from the virus, swamping the number of deaths from opioid abuse or gun violence over the last four years. This figure represents excess deaths caused by Covid compared with death tolls of prior years, so it can’t be dismissed as overcounting people who would otherwise have died.

A masked patient arrives at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York, April 13, 2020. PHOTO: JOHN MINCHILLO/ASSOCIATED PRESS

The disease has erased much of our progress in life expectancy in the U.S., which is now lower than it was nearly two decades ago. And the deaths continue: Covid will remain a top 10 killer for a few more years. More than 5% of American adults are currently experiencing long Covid, too, which is not fully preventable by vaccination and for which there is currently no cure. These individuals will place continuing demands on our healthcare system.

Covid remains much more serious than the usual seasonal flu. The truth is, it’s just dumb luck that this particular coronavirus did not kill 10 million or even 100 million Americans, and that it primarily afflicted people who were old and sometimes already sick. If the virus had killed, say, 10% of the people it infected, as some other coronaviruses do, rather than having a 0.5-0.8% mortality rate, or if it had mainly killed children, as was the case with polio, we would likely have responded very differently.

Deaths among the elderly and sick do not generate the same sympathy or economic disruption as the premature loss of children or adults in their prime. (Polio at its annual peak in the 1950s resulted in just over 3,000 deaths in the U.S., but the national response was overwhelming.) Some politicians used Covid’s “old and sickly” profile to minimize the virus, while other officials exaggerated or misread the risks to school-age children, a posture that has yet to be fully reckoned with. Given the early sense of shared purpose in combating the virus, across red and blue states alike, these mistakes were unfortunate.

The relative indifference to the aged in our society has contributed to the present sense of just moving on from Covid. But this raises the question of why we were so unmoved by their plight. The many human beings who died were our fellow citizens, our parents and grandparents, friends and neighbors.

We were also lucky that highly effective and safe mRNA vaccines emerged so quickly. Covid was the first pandemic in history to feature the development of such a powerful vaccine while the pathogen was still at its outset. The efforts to make a vaccine could just as easily have resulted in abject failure or a very long delay, as with previous vaccine programs. A much higher mortality rate without vaccines would likely have resulted in greater consensus not just for lockdowns and mask mandates but perhaps even for military intervention, as imagined in the movie “Contagion.”

Yet despite the astonishing contributions of scientists to ending the pandemic and minimizing its impact, Americans’ trust in science has declined over the last four years, among Democrats as well as Republicans. According to a Pew survey, in October 2023 just 57% of Americans said science has had a mostly positive effect on society, down 8 points since November 2021 and down 16 points since before the start of the pandemic.

A woman in a senior living center in Utah talks to her great-granddaughter through a protective barrier, April 23, 2020. PHOTO: RICK BOWMER/ASSOCIATED PRESS

This paradox is less surprising when we consider that suspicion of authority and expertise is a common byproduct of pandemics going back to the Black Death. People tend to lose confidence when there is a threat that institutions are unable to fully control. And this distrust is not restricted to scientists. Polls show a similar decline in confidence over the pandemic period in institutions as diverse as higher education, the military, the Supreme Court, the presidency and organized religion.

New vaccines for controlling Covid are on the horizon, and vaccine manufacturers have their own reasons for asking us not to forget the disease. Moderna, for instance, continues to offer webinars for physicians to “examine the latest uptick in Covid-19 cases” and to learn “recommended dosing protocols to ensure maximum protection.”

Drug companies will be swimming against the tide, however, because the public no longer sees Covid as a serious threat. Despite the pandemic’s lingering consequences, we are beginning the process of forgetting, as people have done after every other pandemic in history.

Nor has it helped that Americans had such different experiences of Covid. It mattered a great deal whether you lived in Vermont or Florida; whether you were a frontline worker showing up every day or a knowledge worker hunkered down in a beach house; whether you were one of the 216,000 children (as of 2022) who lost a parent or other caregiver, or you did not know a single person who died. In a time of political polarization and divergent views of what America is about, it should not be surprising if Americans cannot coalesce around a collective memory of the pandemic. What will remain is public forgetting and private remembrance.

And so I worry that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Our ancestors tried to warn us: The Bible is full of plagues, and the Iliad opens with the Greeks being brought low by Apollo’s plague-giving arrows.

The risk is certainly increasing. For a combination of reasons, including climate change and population migration, humans are coming into more contact with wild animals and their diseases, and we have seen a rise in the number of new pathogens over the past half-century—just think of HIV, Ebola, Hantavirus, Zika, MERS, West Nile fever, Bartonellosis. Respiratory pandemics may also be increasing in frequency. They used to arrive every 10 to 30 years, with serious ones striking once a century; now they’re coming more often.

It’s only a matter of time before we face another devastating pandemic. We will have new tools at our disposal to confront the threat, but it’s unclear whether we will have new wisdom. We may just have to shoulder again the timeless burden of having forgotten the past.

Nicholas Christakis is the Sterling Professor of Social and Natural Science at Yale University and the author of “Apollo’s Arrow: The Profound and Enduring Impact of Coronavirus on the Way We Live.”

Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

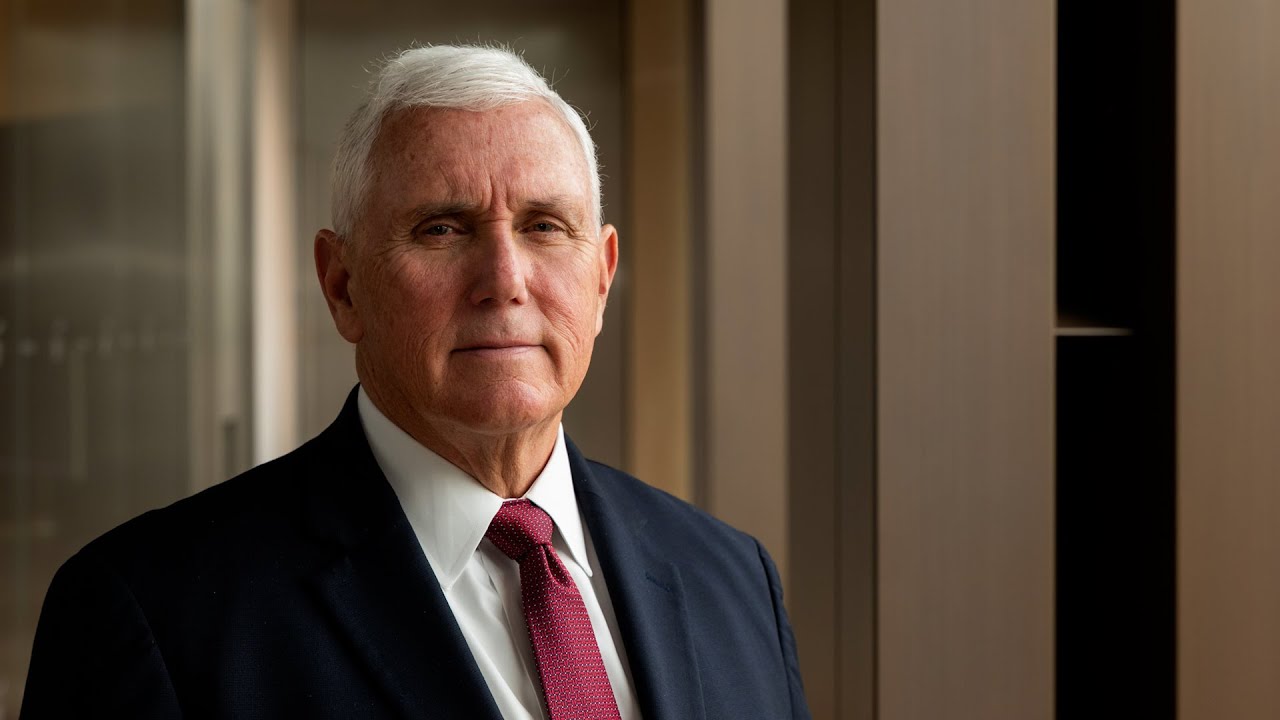

Mike Pence on U.S. Leadership and Global Strategy

Former Vice President of the United States, Mike Pence, shares his thoughts about President Trump’s framework on trying to acquire Greenland, and discusses what he…

Thought Leader: Mike Pence

Barbara Corcoran on Why Most Entrepreneurs Fail

Shark Tank star and real estate mogul Barbara Corcoran shares her unfiltered advice on entrepreneurship, investing, and building long-term success. Corcoran explains how she evaluates…

Thought Leader: Barbara Corcoran