David Frum: Voting Against Trump

Notorious RINO and Atlantic writer David Frum joins Jamie Weinstein to explain why he’s voting for Kamala Harris this election. Frum, a former speechwriter for President…

Thought Leader: David Frum

The great operational question before us is not “Is Joe Biden too old?” The question is “Do you trust the delegates to the Democratic convention in Chicago to replace the present ticket with a supposedly more winning ticket without ripping their party apart in catastrophic ways?”

On this issue, I am reminded of the memorable definition of a conservative offered by the Civil War veteran and writer Ambrose Bierce: one “who is enamored of existing evils, as distinguished from the Liberal who wishes to replace them with others.” So call me an Ambrose Bierce conservative.

Here’s just one data point to keep in mind. Joe Biden beat Donald Trump in 2020 in great part because he ran much better among white men than Hillary Clinton did in 2016. In 2016, Trump won white men by a margin of 30 points; in 2020, Trump won white men by a margin of only 17 points.

I notice that when Democrats speculate about alternative tickets for this election, they speculate about pairings of presidential and vice-presidential nominees intended to excite different elements of the party base. But the Democratic Party does not have as singular a “base” as Republicans do.

Educated urbanites are one Democratic base. Church-affiliated southern Black voters are a different Democratic base. Organized labor, especially in the industrial Midwest, is a third base. The Democrats are a coalition party, not a base party, and they need coalition leadership.

That’s what Biden, for all of his evident frailties, has provided. And one reason so many ardent Democrats are ready to repudiate him now is that they do not like coalition leadership.

“Democrats fall in love; Republicans fall in line” was the old joke that got reversed in 2020. Republicans loved Trump. Democrats accepted Biden. Now Democrats are out of love and yearn to fall in love again.

The need to fall in love is why Roy Cooper’s name is not mentioned. Cooper is the two-term governor of the purple state North Carolina. The need to fall in love is also why we don’t hear much mention of Katie Hobbs, the governor of suddenly purple Arizona, or Amy Klobuchar, the thrice-elected senator from Minnesota, or even the great Democratic hope from Kentucky, two-term governor Andy Beshear. These are steady, moderate figures who don’t rev up the various activist groups the same way that the more mentioned names do. Who knows whether a ticket including two such figures would, in fact, perform better than Joe Biden–Kamala Harris? But there’s more reason to hope so than there is with the more frequently mentioned names advanced by activists.

The trouble is that the Democratic pressure groups veer far from the ground on which American elections are decided. Cooper wants to sign trade deals even though his party distrusts them. Hobbs is tough on immigration and border security. Klobuchar is a former prosecutor who wants more cops on the street. Beshear woos coal country by avoiding mention of climate change.

The point, however, is not that any of these people—or other rising centrist Democrats like them—would necessarily be better than a Biden-Harris ticket. Biden has been tested in years of national elections; his strengths and weaknesses are known. The alternatives are untested, and who knows how they would actually perform?

That’s what presidential primaries are designed to test. But the oft-touted people get attention not because of their success in winning purple states and tough elections but because they perform well on television, or because activist groups approve of them, or because they match some preconception about how to mobilize this or that electoral bloc.

People who appear on political TV shows or write punditry are rewarded for saying bold, unexpected things. These talkers and writers also tend to consume a lot of political information, and react fast and loud to new developments. Most voters react more slowly and quietly, if they react at all.

Political specialists typically worry that ordinary voters are obsessed with personality and celebrity. But it’s the specialists who are familiar with political personalities. For less engaged voters, the parties are strong brands, and their image resists change.

In contrast, individual candidates need years and years of work to establish even a hazy identity. Trump has been a garish American icon for more than four decades. Biden has been in frontline politics even longer, first as a senator, then as vice president, and now as president. If Democrats execute a hasty change of nominee, they’re very likely to end up with either someone most Americans will never feel they know—or, worse, someone who gets defined by Trump with the backing of hundreds of millions of dollars in Republican campaign funds.

A smart challenger always wants to keep attention on the incumbent and his alleged failings. Got a problem? Blame the incumbent. One of Trump’s greatest liabilities as a political candidate has always been his craving for the spotlight. Until last week’s presidential debate, both Trump and Biden in effect agreed that the 2024 election should be a referendum on Trump. Biden’s flailing performance on debate night redirected attention to Biden and his weaknesses—and, for once, Trump had the self-discipline not to distract from the spectacle of his opponent harming himself. Trump has even managed to keep his mouth shut since then, while Democrats engage in further rounds of self-flagellation.

If Biden gets dumped and Democrats plunge into a civil war of who should replace him, Trump won’t even need that self-discipline: The story will be all Democratic disaster, all the time. The story told about the Democrats post–Biden dump would not be about their superb record on job creation since 2021, or about faster-than-inflation wage growth for middle-income and low-income workers, or about the funds for infrastructure and a greener economy, or about their success in reducing crime; it wouldn’t be about the Republican veto of immigration enforcement, or about Biden’s rebuilding of relationships with democratic allies, or about Democrats’ tireless work to defend women’s freedom, or about the party’s support for Ukraine and Israel in each nation’s war of self-defense. The story would be one of chaos and fratricide and splits, along lines of race and sex and ideology.

The news is not always good. The fight is not always easy. Sometimes, you take a hit, and sometimes, the hit is deserved (those may be the ones that hurt the most). What then? The answer to that question is what General Ulysses S. Grant said after the Union Army’s terrible first day at the Battle of Shiloh, in 1862: “Lick ’em tomorrow, though.”

David Frum: Voting Against Trump

Notorious RINO and Atlantic writer David Frum joins Jamie Weinstein to explain why he’s voting for Kamala Harris this election. Frum, a former speechwriter for President…

Thought Leader: David Frum

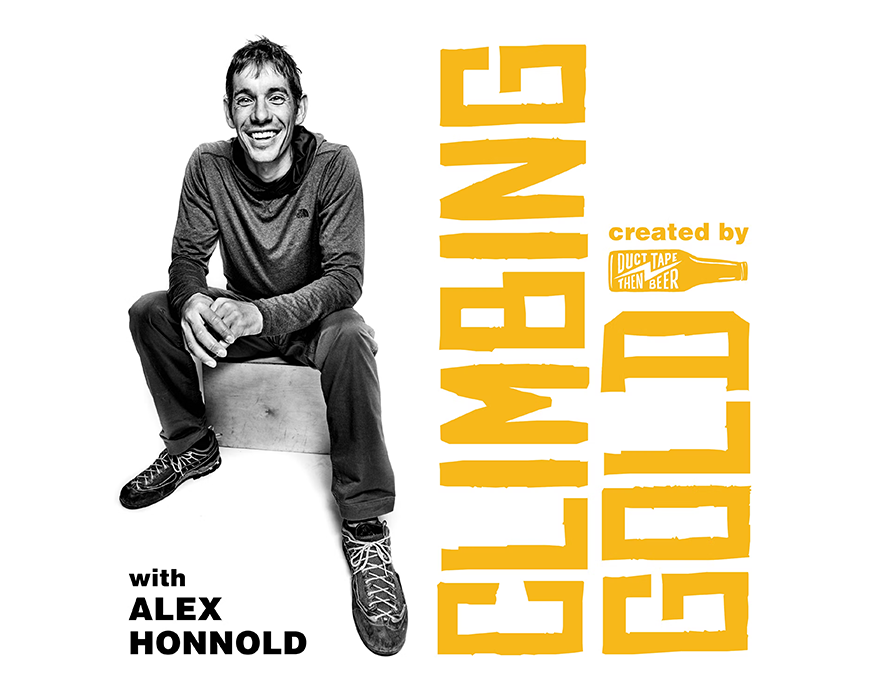

This is the latest episode of Climbing Gold with Alex Honnold. Tucked away in a corner of Chilean Patagonia, Valle Cochamó wasn’t going to stay hidden…

Thought Leader: Alex Honnold

Sanjay Gupta: Self-Exams Matter

This is the latest episode of Chasing Life with Dr. Sanjay Gupta. Sara Sidner is a hard-hitting CNN journalist. Ananda Lewis is a content creator and former…

Thought Leader: Sanjay Gupta