Mediaite: Can you start by giving us an overview on what measures the Chinese government is taking nationwide to stop a second outbreak of the virus?

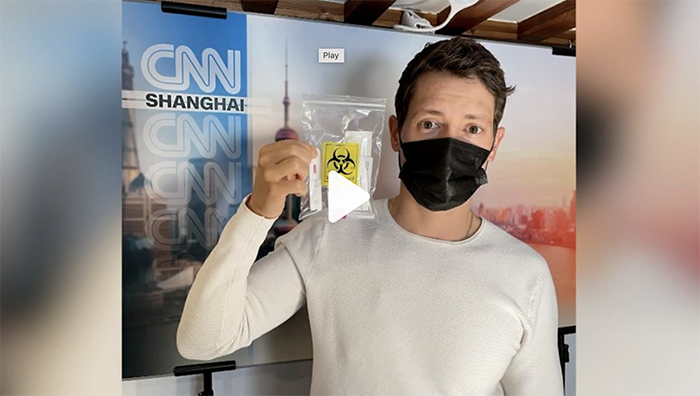

Culver: China has essentially isolated itself from the rest of the world. Nearly all foreigners — with only a few visa exceptions — are blocked from entering. Chinese nationals and those with specific visas permitted to enter, will immediately get tested and put into quarantine for at least 14 days upon arrival.

That’s for a return to a resemblance of the pre-outbreak life within China. In major cities like, Shanghai — where my team and I currently working — restaurants and shopping districts are crowded once again. However, face masks are mandatory, temperature screenings are frequent and contact tracing is maintained through your cell phone (using a local government issued QR code) to as to assess a person’s potential exposure to the virus. In other parts of the country, for example in Wuhan, fast food restaurants have blocked customers from entering and instead handle take-out orders at the storefront. Many convenience stores have mimicked that model. And it appears to reassure both customers and staff.

And further proof that not everything is done uniformly across the country, while many places are “reopening” some cities and towns are just now locking down and building up hospital capacity. It is happening at a much smaller scale compared with what we were witnessing in January and February — at the peak. And it is mostly concentrated along the border with Russia, where a surge of imported cases caused a spike in infections.

What are the most striking differences between Wuhan when you left the city in January and Wuhan when you returned three months later?

At first glance, Wuhan — a metropolis larger than any US city but considered a second-tier size in China — looks the same. But beneath its facade of normalcy, you see the long-term destruction done to the core. I’ve covered a lot of hurricanes and Wuhan feels like a city emerging from the aftermath of a Category 5, minus the physical damage. The spirit of the people is cautiously optimistic. They understand they need — and want — to be back outside and back to work. But many of them do so with a deep hesitation.

Prior to the lockdown on January 23, we were there and got a sense of the incoming storm. Though, admittedly, we had no idea how intense it would actually be. And there was a complacency among many people. I remember going to a produce market on January 22. We were wearing our masks and gloves. About half of the people walked around seemingly confident that the air they were breathing was clean and the people they were in contact with were harmless. The next day the city went on an unprecedented and brutal 76-day lockdown. Many people sealed inside their homes for much of that period.

The effects of such a lockdown are going to take weeks to process. There’s a mental health aspect that you see in the hesitation of folks on the street. There’s a distrust and uneasiness directed to foreigners out of fear that the threat is now external. As state media here stresses the number of imported cases are increasingly more than the locally transmitted ones. And then there’s the economic aspect. Driving through some of the commercial streets, more than half of the shops and restaurants are closed. Several of the small business owners told us they will likely never reopen. They couldn’t weather the outbreak.

Your reports have pointed to the discrepancy between China’s official death toll and the quantity of funeral urns that have been distributed. There has been a lot of skepticism about the accuracy of their statistics and other misinformation coming from the country. How seriously should we take China’s claims that the virus is under control with only a few thousand deaths?

Early on our reporting revealed extensive cover-up, underreporting, and mishandling at the local level within China. We connected with many in Wuhan who risked their own safety to divulge the desperate truths of what was happening. One doctor, Li Wenliang, even spoke to us by phone briefly to describe his attempts to sound the alarm of the then mysterious illness that was going around. He was instead reprimanded by police and later contracted the virus and died less than a week after we spoke with him by phone. The Chinese have also repeatedly changed the methodology in which they count cases, casting doubt on their transparency. However, anecdotally we know that when they fear a hotspot surfacing or a potential spike, they will not hesitate to respond sharply by locking down a city or province. Given the easing of restrictions currently underway internally, it is clear they’ve gained control over the outbreak domestically. However, it’s come with the sealing off of borders, invasive contract tracing and widespread testing. The real test of their effectiveness in containing the spread will come as travel internationally resumes.

The U.S. has seen protests over the lockdowns that have brought the economy to a halt. Many are calling for public health to take a backseat to allow the economy to restart. Is there a similar conversation in China about weighing public health with the economic impact?

Since making his first public appearance and addressing the outbreak in early February, President Xi Jinping has emphasized two things: containing the virus and stabilizing the economy. I would argue that in China maintaining economic growth is even more important than in the US. While health safety is paramount, in China prosperity is more than just providing your people with material comforts, it’s part of the authoritarian government’s bargain with the greater populace that in turn maintains social stability. Without it, the Central Government and Party risk losing its control.

There have been mixed messages on whether the Trump administration has evidence the virus originated from the Wuhan Institute of Virology. Trump said he has seen evidence, but declined to clarify. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo gave a confounding statement on the question in a recent interview. Dr. Anthony Fauci has said the virus likely emerged naturally. Have you seen any evidence supporting the theory that the virus came from a Chinese laboratory?

Culver: There is circumstantial evidence that puts the origins of this virus in a Wuhan laboratory, including the fact that the Wuhan Institute of Virology is located within miles of the Huanan Seafood Market — thought to be the original source — as the lab studies coronaviruses and there have been several unverified photos surfacing suggesting substandard lab conditions. But the evidence is far from concrete. And now with US allies — including Australia — downplaying the likelihood that it originated in a lab, the U.S. faces a growing obstacle in making such a case.

You said on Tuesday that tensions between China and the U.S. could go beyond trade war conflict and lead to “actual war conflict.” Could you elaborate on why you believe this might be the case?

China is growing increasingly distrustful of U.S. intentions. So much so, that Reuters reported on an internal document that was reportedly seen by Chinese leadership, including President Xi Jinping, that suggests global anti-China sentiment is at its highest since the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. Reuters says the report also warns that hostility promoted by the United States in the aftermath of the pandemic could lead to a worst-case scenario of armed conflict between the two countries.

Add to that the growing nationalism within China, an augmented distrust of foreign media and rising naval tensions on the South China Sea. The climate in many ways feels primed for conflict and heated rhetoric — the so-called war of words — could fuel emotions that in turn could spark action. However, both sides when taped into rational thinking share more reasons for restraint than to induce conflict. So long as that reasoning prevails, tensions should be kept in check.

If we briefly take away concerns about how much China has covered up during the pandemic, are there any lessons the U.S. can learn from the country in order to suppress the spread of the virus and eventually open up?

Putting aside China’s obvious mishandling at the local level amidst the start of the outbreak, China’s advantage as an authoritarian state is that localities do not question the Central Government’s decisions. To that point, when cities were locked down and schools shuttered the entire country mobilized to enforce social distancing, wearing of masks, widespread testing and forced quarantines. This in no way endorses the harsh lockdowns, as the damage incurred for cities like Wuhan could take months or years to heal, but given the resumption of normalcy underway in other parts of the country — like here in Shanghai — it does suggest there has been a level of effectiveness that’s resulted from the extreme actions.

Perhaps the greatest takeaway, however, comes from private businesses that have worked to reopen with new procedures and methods that reassure both consumers and employees. This unprecedented period and its accompanying restrictions have forced innovations and sacrifices that allow the world’s second largest economy to resume business, even as the rest of the world is still struggling to navigate the uncertain future.