“There is this recognition of this moment and how fleeting it is, and an evaluation that, absent the trifecta of control, it is very hard to move big policy,” said a senior official at one of the party’s leading outside advocacy groups, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal strategizing. “So you have to take your shot. I think that’s part of what undergirds ‘Go big.’”

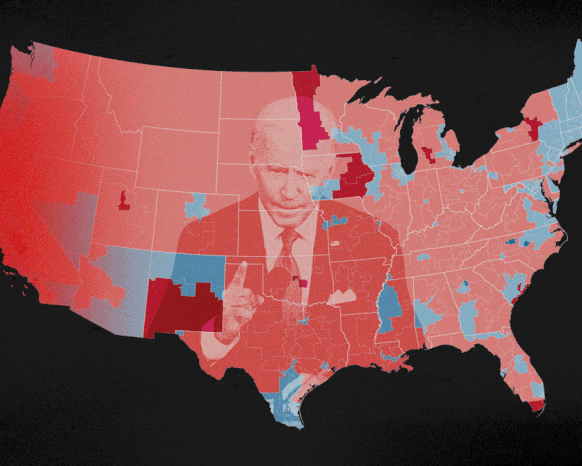

In one sense, past presidents’ first two years in office offer Biden and congressional Democrats reason to be optimistic about executing their plans. Looked at another way, though, that history is discouraging, dauntingly so.

What’s encouraging is how past presidents have managed to push through important parts of their agenda. Presidents don’t get everything they want during that initial two-year period. Clinton, for instance, failed to pass comprehensive health-care reform, and Donald Trump failed to repeal the comprehensive reform that Obama did pass—the Affordable Care Act. But presidents whose party controls Congress typically do pass some version of their core economic proposals during their first two years, even if it usually happens after some significant remodeling.

Trump and George W. Bush each pushed massive tax cuts through a Republican-controlled Congress during their first year in office. In his first months, Ronald Reagan muscled through a landmark tax reduction, despite a Congress divided between a Republican Senate and a Democratic House. With the support of a Democratic-controlled Congress, Obama signed both a large economic-stimulus package and the ACA, and Clinton, by the narrowest possible margins, likewise enacted his deficit-reduction and public-investment plans.

In each of these cases, the president was compelled to abandon or trim key elements of his blueprint. Congress forced Clinton to jettison his BTU tax (an early attempt to tax energy consumption) and accept the creation of a commission to study entitlement cuts. Dissent from two moderate Republican senators forced Bush to slash his tax cut by nearly one-fourth. Obama was compelled to reduce his stimulus spending to win over Senate Republican votes, and to drop the ACA’s public option to obtain the last Democratic votes he needed. Even Reagan’s watershed reductions in personal-income-tax rates were scaled back. Yet while these concessions were seen at the time as major setbacks, they are now remembered, if at all, as merely smudges on legislative achievements that rank among each of these presidents’ most consequential.

This history augurs well for Congress eventually approving some version of the infrastructure and human-capital plans Biden touted last night, even if the plans are adjusted to win approval from the Democratic Party’s most conservative senators, such as West Virginia’s Joe Manchin. (Democrats can pass most of Biden’s economic agenda through the reconciliation process, which requires only a simple-majority vote in the Senate. His noneconomic priorities face much dimmer prospects of passing in the upper chamber, unless Senate Democrats agree to curtail the filibuster.) Democrats often blame the devastating losses Obama suffered in 2010—he lost more House seats than any president in a midterm since 1938—on his administration’s overly cautious approach, and they don’t want to repeat that mistake. “Trying to placate the Republicans with a bunch of tax cuts and going for a more modest package, thinking that would gain support, turned out to be dead wrong,” Price told me. “You got a weaker bill and no bipartisan support: the worst of both worlds. We are trying to get a stronger bill and assuming the net effect will be to increase pressure on Republicans” who are opposing it.