Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

Pandemics have always bred political lunacy, but societies develop resistance to both.

Major pandemics often coincide with religious or political contagions. In his “History of the Peloponnesian War,” Thucydides records how, during the plague that devastated Athens between 430 and 426 BC, people seemed to lose their moral compasses. “As the disaster passed all bounds, men, not knowing what was to become of them, became utterly careless of everything, whether sacred or profane. … Perseverance in what men called honor was popular with none. … Fear of gods or law of man there was none to restrain them.” Disregard for both religion and law undermined the city’s famous democracy, leading to a reduction of noncitizen residents and ultimately to a period of oligarchy in 411.

During the Black Death that swept across Europe in the 1340s, flagellant orders roamed from town to town, ritually whipping themselves in acts of atonement intended to ward off divine wrath. Calling themselves Cross-Bearers, Flagellant Brethren or Brethren of the Cross, they wore white robes with a red cross on the front and back and similar headgear. On arriving in a town, the brethren would proceed to its church, form a circle, and prostrate themselves, arms outstretched as if crucified. On the command “Arise, by the honor of pure martyrdom,” they would stand up and beat themselves with leather scourges tipped with iron spikes, chanting hymns as they did so, periodically falling back to the ground “as though struck by lightning,” according to a contemporary source.

There was more than masochism at work here. The flagellants were a millenarian movement with a potentially revolutionary agenda that flouted the authority of the clergy and directed popular wrath against Jewish communities, which were accused of willfully spreading the plague or of inviting divine retribution by their repudiation of Christ. Jews were massacred in numerous towns, notably Frankfurt, Mainz and Cologne.

The worst pandemic of the modern era, the misnamed Spanish influenza of 1918-1919, coincided with a wave of violent revolution as the ideas of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin and his fellow Bolsheviks swept the Russian Empire and sparked proletarian risings all over the world. Many conservatives (including Winston Churchill and Herbert Hoover) explicitly referred to the “plague of Bolshevism.” Churchill was especially fond of the metaphor. In a 1920 article entitled, “The Poison Peril,” he railed against “a poisoned Russia, an infected Russia, a plague-bearing Russia, a Russia of armed hordes … accompanied and preceded by the swarms of typhus bearing vermin which slay the bodies of men, and political doctrines which destroy the health and even the soul of nations.”

The most radical anti-Bolsheviks in Europe — among them Adolf Hitler — used similar biological metaphors (“racial tuberculosis”) to characterize not only the ideology of the Soviet regime but also the Jews, whom they regarded as Lenin’s confederates. It became conventional on the American right in the 1930s to argue that Hitler had “saved all Europe from the red plague of Bolshevism,” in the words of the German-American poet George Sylvester Viereck. In reality, of course, National Socialism was itself a deadly ideological contagion that spread through the German population in ways that historians still struggle to understand.

It was therefore with the deepest anxiety that I watched the events in Washington last Wednesday, as a mob whipped into revolutionary fervor by President Donald Trump overran the Capitol in attempt to disrupt the congressional certification of the Electoral College’s votes, the final step in the constitutionally prescribed process of presidential election.

It does not matter which foreign term you wish to use: coup, putsch, autogolpe — take your pick. Since Nov. 3, Trump has attempted to overturn the result of the presidential election he lost, using mafia tactics (listen to his call to the Georgia secretary of state, Brad Raffensberger), as well as cynical “lawfare.” On Wednesday, he not only egged on the mob; he later said he “loved” them for what they had done. This clearly violated his oath of office to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

There are perfectly good English words for what Trump did and, if you could call up the founders and ask for their opinion, they would use them. Trump is a demagogue and a would-be tyrant whose disregard for the rule of law and encouragement of sedition and insurrection have, very fortunately for us all, been thwarted by his own incompetence and, of course, the separation of powers and other constitutional checks the founders devised, in the full awareness that one day such a man might become president.

What, I’ve been asked, is the best historical analogy for last week’s events in Washington? None fits perfectly. Oliver Cromwell’s dissolution of England’s Long Parliament in 1653? The obvious difference is that Cromwell succeeded in establishing himself as lord protector. The dissolution of the French National Assembly by Louis Napoleon Bonaparte in 1851? Again, Bonaparte actually succeeded in establishing the Second Empire. How about Mussolini’s March on Rome in 1922? The difference there is that King Victor Emmanuel threw Prime Minister Luigi Facta under the bus by refusing to declare a state of emergency, and then appointing Mussolini in his place.

Hitler’s Beer Hall Putsch of 1923 was, like Thursday’s affair, a fiasco. But it didn’t happen in the national capital and it wasn’t inspired by either the German chancellor or the president. Moreover, it ended with quite a lot of shooting (16 Nazis were killed on the streets of Munich) and the imprisonment of Hitler and other conspirators — in marked contrast to the mysterious leniency with which the Trumpists were treated on Thursday, with an exception being Ashli Babbitt, who was shot by a plainclothes Capitol Police officer as she climbed through the smashed door to the Speaker’s Lobby.

My Bloomberg Opinion colleague Noah Smith draws a parallel with Japan in the 1930s, but there (as in multiple South American and Middle Eastern coups) a key role was played by ultranationalist junior officers in the military. Something similar goes for the Tejerazo, the storming of the Spanish parliament by 200 Civil Guard officers led by Lieutenant Colonel Antonio Tejero in 1981. By contrast, the American military would do nothing to support an unconstitutional seizure of power. Support for Trump diminishes the higher up the command structure you go, with recently retired generals among his most vehement critics.

True, there is considerable support for Trump among police officers across the nation, and video footage from Wednesday seemed to show some Capitol cops fraternizing with the mob, even abetting them. On the whole, however, the police seem simply to have been outnumbered and overrun. It remains unclear who gave the orders not to give the pro-Trump mob the same tough treatment meted out to Black Lives Matters protesters in the summer. But I doubt this was part of a coup conspiracy.

There is another reason none of these analogies works: They all omit the peculiar conditions created by a pandemic. It is not coincidental that the nadir of modern American politics was plumbed last week just as the third wave of Covid-19 seemed to near its crest. On Thursday, new daily cases in the U.S. reached a pandemic record of 260,973; daily deaths exceeded 4,000 for the first time, bringing the total death toll to more than 370,000. Another 130,000 Americans are hospitalized. Only in terms of excess mortality relative to seasonal averages has the third wave not yet surpassed the first.

Pandemics, remember, are associated with religious and political extremism. The fear of illness, mutual suspicion, quack theories, hypochondria, hyper-skepticism and general mental dislocation caused by social distancing, lockdowns and unemployment — taken together, these things tend to generate outlandish behavior.

To the historian, it was not altogether surprising back in the summer to see hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of mostly white protesters take to the streets in processions of expiation for the sin of racism. The left-wing violence that turned parts of Portland, Seattle and Kenosha, Wisconsin, into no-go zones was more destructive than the right-wing invasion of the Capitol, even if the latter’s political significance was greater.

Look, if you want evidence of pandemic madness, at the people who ran amok among the legislature last week. The idea that this was a false-flag operation by far-left Antifa in disguise is obviously absurd. Although the mob seems to have included a few retired military members or off-duty police who had the training and the tools for a serious terrorist attack, this was mostly the lunatic fringe of the American far right in an unholy alliance with the QAnon conspiracy cult.

The bearded nutter with the “Camp Auschwitz” sweatshirt and the thug with the “6MWE” T-shirt (which stands for “Six million weren’t enough”) rubbed shoulders with the “Q shaman,” Jake Angeli, he of the buffalo horns, tattoos and stars-and-stripes face paint. Nick Fuentes, who leads the far-right “Groyper Army,” was pictured inside the Capitol next to another fascist who goes by “Baked Alaska.” There were Confederate flags and nooses, but also QAnon signs (“The Children Cry Out for Justice”), crusader crosses (yes, that red cross on white again), and anti-circumcision placards.

For a brief moment on Wednesday afternoon, I felt a strong temptation to throw up my hands and admit that this really was Weimar America after all, and that Trump was indeed the tyrant depicted in so many articles over the past five years.

A closer look at this motley crew of misfits brought me back to reality — that, and the realization that, far from proclaiming presidential rule by decree and securing the TV stations (which is what coup leaders are supposed to do), Trump and his children were vacuously watching the mayhem on television. Just as the QAnon (and KKKAnon) mob were too busy filming their own antics to prevent the members of Congress making their escape, so the putative dictator was too preoccupied with fulminating against his vice president to anticipate his own summary exclusion from the major social media platforms. (The people reflexively cheering Facebook’s action might ask themselves if that was last week’s successful coup. It was certainly the starkest revelation yet of Mark Zuckerberg’s power.)

It is possible — I cannot rule it out — that Trump and Trumpism will persist long after his departure from the White House, whether that happens tomorrow via the 25th Amendment, next week via high-speed impeachment, or on Inauguration Day. He would not be the first leader in history to linger long after his departure from high office, insisting that his loyal followers treat him as the rightful president, a kind of 21st-century version of the Jacobite Pretenders to the British throne.

Nor would Trump be the first demagogue to be nominated as a presidential candidate more than once by his party: William Jennings Bryan (who at least knew how to concede defeat) was the Democratic candidate three times from 1896 to 1908. Even if Trump’s health were to give out, we know from the three generations of the Le Pen family in France that right-wing dynasties can be remarkably durable.

The dominant media narrative of our time is of profound political polarization, with the potential one day to escalate into civil war. Perhaps that is right, and what we really witnessed last week was the Trumpist equivalent of John Brown’s abortive revolt at Harpers Ferry, a precursor to the Civil War (even if the extreme Trumpists’ views on race are clearly the opposite of the abolitionist Brown’s).

If that pessimistic view is right, then we are only just emerging from the first wave of Trumpism. Like the new variants of Covid-19 discovered in England and South Africa, which spread more rapidly than earlier strains, it could surge back in an even more virulent form.

But my contrarian view is that, rather than worsening the country’s polarization, the events of the past few months have in fact substantially restored the center ground. Trump lost in the November election; but so did the far left of the Democratic Party. Biden personifies the middle of the road. He didn’t sweep to power on a blue wave, because many voters who didn’t back Trump nevertheless voted for Republicans down the ballot. But for Trump’s criminal behavior, his party might have held the Senate.

Vice President Mike Pence’s letter breaking with Trump and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s speech rejecting the president’s challenge to Biden’s victory on Wednesday marked the long-overdue end of the Republican establishment’s sordid affair with Trump. The narrowness of the Democrats’ majorities in the Senate and House should also help the center hold. There are now incentives on both sides to work together, if only to repair the terrible damage caused by Trump’s mishandling of the pandemic.

This, at least, is my earnest hope: That, having once been infected by the virus of antidemocratic politics, Americans have now acquired some resistance to it. The optimistic view of the pandemic is that natural infection plus mass vaccination will get the U.S. to herd immunity by around May. The optimistic view of politics is that we can achieve herd immunity against Trumpism in a roughly similar timeframe.

Shorn of power, assailed by litigation, his finances tottering and his access to social media abruptly curtailed, Trump may fade as quickly as a virus with a reproduction number below 1 — to become no more than a seasonal malady, threatening only to those with the intellectual equivalent of comorbidities. The lesson of history is that pandemics eventually end — and so do political manias of the sort that briefly seized the Capitol last week.

Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

Patrick McGee: Tesla’s Robotaxi Bait and Switch

Elon Musk called self-driving cars a ‘solved problem’ 10 years ago. So how come he’s still working on it? In a new column, Patrick McGee…

Thought Leader: Patrick McGee

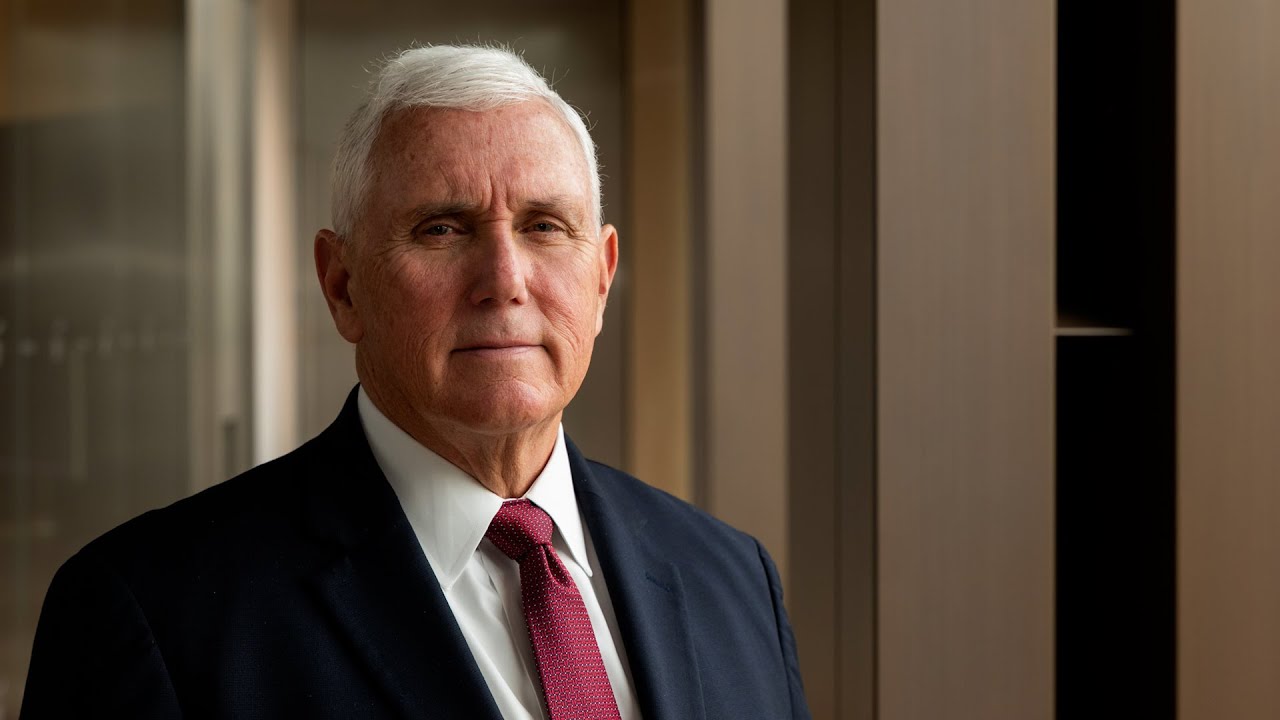

Mike Pence on U.S. Leadership and Global Strategy

Former Vice President of the United States, Mike Pence, shares his thoughts about President Trump’s framework on trying to acquire Greenland, and discusses what he…

Thought Leader: Mike Pence