Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

If no one in your circle of family and friends is mentally ill, count yourself lucky — or maybe you’re just deluding yourself. In my intimate social network, I can think of at least six cases.

I’m not talking just about relatives or friends or the children of friends who say they are depressed. I’m talking about medically diagnosed mental illness requiring treatment. Three cases of chronic addiction. Two cases of severe eating disorder. One case of attempted suicide. And those are just the ones I know about. I’m also aware of two overdose deaths in my wider social circle. These may or may not have been associated with psychological problems.

The standard headline for a piece on this subject is “The Kids Are Not All Right,” an allusion to The Who’s 1965 classic, The Kids Are Alright. “I don’t mind other guys dancing with my girl,” sang Roger Daltrey, in the days when The Who still wanted to sound like a badly behaved version of The Beatles and guys still danced with girls. However, I think I’ll go with another British pop classic, from seven years later: Slade’s Mama Weer All Crazee Now.

Derek Thompson has been writing intelligently on this subject for the Atlantic, so let’s start with his take on the latest Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), published earlier this month by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The takeaway was that “American teenagers — especially girls and kids who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or questioning — are ‘engulfed’ in historic rates of anxiety and sadness.”

For Thompson, the best explanations are “the decline of physical-world interactions [due to] the prevalence of social-media use; the decline of time spent with friends; a more stressful world of mass-shooting events and existential crises such as global warming; and changes in parenting that might be reducing kids’ mental resilience.” The Covid-19 pandemic made an already bad trend worse.

My friend Jonathan Haidt of New York University has made similar arguments. According to Haidt, there has never been a generation as “depressed, anxious and fragile” as Generation Z, Americans born between 1997 and 2012. They have “extraordinarily high rates of anxiety, depression, self-harm, suicide and fragility.” Haidt lays the blame firmly on social media — to be precise, apps such as Facebook and Instagram on smartphones — and is working on a book making that case. (He’s already published much of his data and a series of related academic articles.)

Not everyone is buying this story. “People are like ‘why are kids so depressed it must be their PHONES!’” tweeted Taylor Lorenz, the Washington Post’s technology columnist, last week. “But [they] never mention the fact that we’re living in a late stage capitalist hellscape during an ongoing deadly pandemic w record wealth inequality, 0 social safety net/job security, as climate change cooks the world.”

“Not to be a doomer,” she added, “but u have to be delusional to look at life in our country rn and have any amt of hope or optimism.” (Actually, I think that does make you a “doomer.”) The obvious response is that, by most objective measures, such as disposable income or access to entertainment, America’s teenagers and 20-somethings are better off than their parents and grandparents were at the same stage in life, and if they could travel back to 1973 they’d encounter something a lot more like a “hellscape.” But that doesn’t explain the current wave of mental illness among the young.

Let’s look at the statistics (there are plenty). According to the non-profit advocacy group Mental Health America’s 2023 report (which is based on 2020 data), 11.5% of American kids aged from 12 to 17 are “experiencing depression that is severely impairing their ability to function,” while 16.4% report “suffering from at least one major depressive episode in the past year.” This is a problem that is getting worse over time. According to Office Practicum, there was “a 27% increase in anxiety and a 24% increase in depression between 2016 and 2019” in this teenage group.

The CDC has some startling data on the mental health of children. Among those aged 3 to 17, the rates of diagnosis for the following conditions are:

Amazingly, 1 in 6 US children aged between 2 and 8 has been diagnosed with a mental, behavioral or developmental disorder. Here, too, the trend looks terrible. The share of children aged 6 to 17 who have ever been diagnosed with either anxiety or depression has been rising since the early 2000s.

In this context, no one should have been surprised by the latest YRBS — which is compiled every two years from surveys of students at a nationally representative sample of public and private high schools. Here are some lowlights:

When you realize that, according to Gallup, 21% of Gen Z Americans now identify as “lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or something else that isn’t heterosexual,” these last statistics imply a staggering number of suicide attempts.

Surveys of course are about what people say, not necessarily what they do or have done. Still, according to Tanz et al. (2022), the number of overdose deaths among Americans aged 14 to 18 rose 94% from 2019 to 2020, and 20% from 2020 to 2021. True, the vast majority of these deaths were due to opioids and illicitly manufactured fentanyl, so this could just be a story of more potent drugs and more tragic mistakes, as opposed to deaths of despair. Note also that two-thirds of those who died from overdoses were male, whereas the survey evidence points to a crisis of female mental health. Nevertheless, it is striking that 41% of teenage overdose victims had evidence of mental health conditions or treatment.

In sum, you can see why the state of adolescent mental health was declared a national emergency in 2021 by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association.

There’s only one glitch with this harrowing narrative: The reality is that there is a mental illness epidemic throughout the population. It’s not just the kids who are not all right.

In 2019-2020, according to Mental Health America, 20.8% of adults were experiencing a mental illness, equivalent to more than 50 million Americans. Admittedly, the percentage of adults reporting serious thoughts of suicide is 4.8%, a quarter of the YRBS figure for high schoolers. However, according to MHA, the rate of substance-use disorder is 15.4% for adults, whereas it is only 6.4% for young people. A staggering 32.6 million people have an alcohol use disorder in the US, nearly all of them adults. Of these, at most 50% overcome their addiction and achieve sustained abstinence, according to Sliedrecht et al. (2019). Most of the estimated 108,000 drug overdose deaths in 2021 were of adults. This scourge is one of the principal reasons why — uniquely in the developed world — US life expectancy fell in 2020 and 2021, despite the fact that the US spends far more per person on health care than any comparable country.

It was the Nobel laureate Angus Deaton and his co-author Anne Case who several years ago coined the phrase “deaths of despair.” But it was not young people in particular they were worried about. It was White non-Hispanic Americans, especially middle-aged ones with only high school diplomas or less. Within this group, they observed an “important, awful, and unexpected” increase in death rates from suicide, drug overdoses and alcohol-related liver disease such as cirrhosis. They also saw an upsurge in illness (ranging from obesity to mental problems). They related all this misery to the problems of economic and social dissolution first identified by Charles Murray in his seminal book Coming Apart.

A recent New York Times report on drug overdose deaths provided a reminder that deaths of despair don’t just happen in the flyover states. According to the city’s chief medical examiner, there were about 2,700 drug overdose deaths in New York in 2021, the highest total in at least two decades, and 2022’s total is likely to be even higher. “If not for the pandemic,” he said, “this would be the public health emergency of our lifetimes.” But it seems clear that the pandemic made the opioid epidemic worse, one contagion exacerbating the other.

Contagion is the key concept if we are to understand our modern malaise, and you cannot understand contagion until you understand the structure of networks. In my 2017 book The Square and the Tower, I quoted Stanford University biology professor Deborah M. Gordon’s argument that online social networks were replicating on a vast scale many of the more insidious features of friendship circles among girls in a middle school. Malicious gossip spreads far faster and further on Facebook than it ever did in the schoolyard.

I also cited research by Holly Shakya and Nicholas Christakis, who used data from 5,208 adults over two years, to argue that “the more you use Facebook, the worse you feel.” I even quoted Facebook’s own research, which came to similar conclusions about the effects of the overuse of social media by students.

All that research was done more than five years ago. It has since been reinforced by studies such as Allcott et al. (2020), which concluded that using social media was a form of addictive behavior. The issue remains a battleground for social scientists, but I remain firmly persuaded that the creation of vast online networks greatly increased our vulnerability to contagions of the mind, including conspiracy theories and “mind viruses” of all kinds.

Into this hyper-networked world came SARS-CoV-2, a genuine virus spread through the air rather than online and capable of causing severe illness or death, especially to elderly or physically vulnerable people. To a truly unprecedented extent, normal economic and social life came to halt. Large proportions of the population were confined to their homes in what resembled mass house-arrest.

It would have been astonishing if the abrupt closure of real-world social networks had not been detrimental to the mental health of a gregarious species of naked apes. And sure enough, according to the World Health Organization last year:

Evidence suggests the pandemic and associated PHSMs [public health and social measures] have led to a worldwide increase in mental health problems, including widespread depression and anxiety. People living with pre-existing mental disorders are also at greater risk of severe illness and death from COVID-19 … There were indications of increased risk in young people and the longer-term impact of the pandemic and associated economic recession on mental health and suicide rates remains a concern …

The most recent Global Burden of Disease study estimated that Covid led to a 28% increase in major depressive disorders and a 26% increase in anxiety disorders. Women have consistently reported larger increases in mental health problems in response to the pandemic than men. Adolescents and young adults have been disproportionately affected compared to younger children and older adults. The most common explanation is that lockdowns — and especially school closures — interrupted a development phase in which social interactions outside the family context are crucial.

On closer inspection, however, the impact of the pandemic on mental health has not been so clear-cut. Suicide rates in most countries did not rise during the pandemic. Of four longitudinal population-based studies that measured and compared depressive and anxiety disorder prevalence before and during the pandemic, two found no change in the prevalence of these disorders, one found a decrease, and only one found an increase.

You might assume that Covid was especially bad for the sanity of healthcare workers. But a meta-analysis (of 206 studies found that the mental health status of healthcare workers was similar to or even better than that of the general population in 2020, the annus horribilis of the pandemic.

I have even come across an article in Elsevier’s Journal of Affective Disorders (Lee et al. 2021) claiming that lockdowns were good for mental health: “The prevalence of clinically significant depressive symptoms,” the authors argue, “was significantly lower in countries wherein governments implemented stringent policies promptly.” Another study (Sutin et al. 2022) finds that the personality trait of “neuroticism declined very slightly in 2020 compared to pre-pandemic”; by 2021–2022 there “was no significant change in neuroticism compared to pre-pandemic levels” and only “small declines in extraversion, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness.”

The reality is that, for most of us, so long as we now feel healthy, the pandemic seems over and whatever hardships it imposed on us lie in the past. The enduring mental health cost is being borne by sufferers of long Covid, an umbrella term for a variety of the lasting “sequelae” that afflict a significant minority of people infected by the virus. These include cognitive impairments such as memory loss, concentration problems, word-finding problems and impaired daily problem-solving — all colloquially known to patients as “brain fog.”

One meta-analysis of 51 studies involving 18,917 Covid patients with an average follow-up of 77 days found that 20.2% of them suffered from cognitive impairment, 19.1% from anxiety symptoms, 15.7% from post-traumatic stress symptoms, and 12.9% from depression symptoms. Another meta-analysis that assessed patients 12 weeks or more after confirmed Covid-19 diagnosis found that 22% experienced cognitive impairment. A one-year follow-up study of 153,848 survivors of Covid in the US Veterans Affairs database found an increased incidence of mental disorder with a relative risk of 1.46 compared to a contemporary group and a historical control group. Douaud et al. (2022) even found evidence that Covid infection was associated with changes in brain structure.

A common argument from mental health professionals is that not enough is being done to help Americans suffering from mental illness, whatever its cause. According to Mental Health America, 93.5% of individuals with a substance-abuse disorder in 2021 did not receive any form of treatment. Over half of adults with a mental illness did not receive treatment. Nearly a quarter of adults who report experiencing 14 or more mentally unhealthy days each month were not able to see a doctor due to costs. One in 10 adults with a mental illness was uninsured.

The problem, we are told, is especially bad for young people. Nearly 60% of those age 12 to 17 with major depression do not receive any mental health treatment. Hoffmann et al. (2022) looked at 5,034 youth suicides from 2015 to 2016 and found that the suicide rate increased as county levels of mental health coverage decreased, after adjusting for demographic and socioeconomic factors.

There is, however, another possibility that cannot be ruled out. With the number of therapists growing faster in the US than average for all occupations — and with mental health services booming in college campuses — young Americans surely have more access to psychotherapy than any previous generation of teenagers and twenty-somethings.

At the same time, from my Baby Boomer vantage point, they seem to have a lot less of what we used to think of as fun. This is the part of the latest YRBS that attracted less comment. “Sexual behaviors,” the report states, “have been improving [sic] for all students, but especially for Black and Hispanic students.” The percentage of high schoolers who have ever had sex fell from 47% in 2011 to 30% in 2021. The share who have had four or more sexual partners was down from 15% to 6%; the share who were currently sexually active was down from 34% to 21%.

As for the supposed substance-abuse epidemic, the proportion of high schoolers who drank alcohol fell from 39% to 23% over the past decade (for boys, it’s down to 19%); the share who currently use marijuana fell from 23% to 16%; the share who had ever used illicit drugs fell from 19% to 13%. And these downward trends apply to all racial and ethnic sub-groups.

The daughter of an English friend of mine began her undergraduate studies at a renowned American university last year. She chose to leave because she found the social atmosphere oppressive. “Everyone seems to have their mental health problem that they want to talk about,” she told me. “I said I didn’t have one and was pretty well-adjusted. They said: ‘Ah, your trauma must be really deeply buried.’”

Some of the most interesting recent research on human emotion has shown that emotional states can be transmitted through a social network. As James H. Fowler and Nicholas Christakis show in their book Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks, “Students with studious roommates become more studious. Diners sitting next to heavy eaters eat more food.” Remarkably, we are able to transmit ideas and behaviors over as many as three degrees of separation — in other words, to our friends’ friends’ friends. One begins to wonder if this is part of what is going on with the mental health epidemic among young people.

When I was a teenager in 1970s Glasgow, the peer group pressure was to drink alcohol, smoke cigarettes and lose one’s virginity. Have a listen to “Mama Weer All Crazee Now” and you’ll see that it’s essentially a song about drinking whisky to excess. We did a lot of that as teenagers. We even used “mental” as a compliment — as in “That party at Big Al’s on Saturday night was totally mental.”

In America today, the peer group pressure among teenagers is to get counseling rather than to get crazee. I feel sorry for Generation Z. Compared with being a teenager in the 1970s, being a teenager in the 2020s seems like no fun at all. But can there really have been as many suicide attempts by high schoolers in 2021 as the YRBS implies — which would be around 2.5 million?

The big mental health pandemic of our time is the one that is driving tens of millions of adults to shorten their lives by suicide or by an addictive intake of alcohol and drugs that amounts to slow suicide. These are the unhappy people who took Slade literally. They just attract less media coverage than the Instagram-induced angst of Generation Z.

Erika Ayers Badan: You Are The Problem (And The Solution)

This is an episode for people grappling with how to manage and how to embrace AI. Good managers in the future will seamlessly balance being…

Thought Leader: Erika Ayers Badan

Patrick McGee: Tesla’s Robotaxi Bait and Switch

Elon Musk called self-driving cars a ‘solved problem’ 10 years ago. So how come he’s still working on it? In a new column, Patrick McGee…

Thought Leader: Patrick McGee

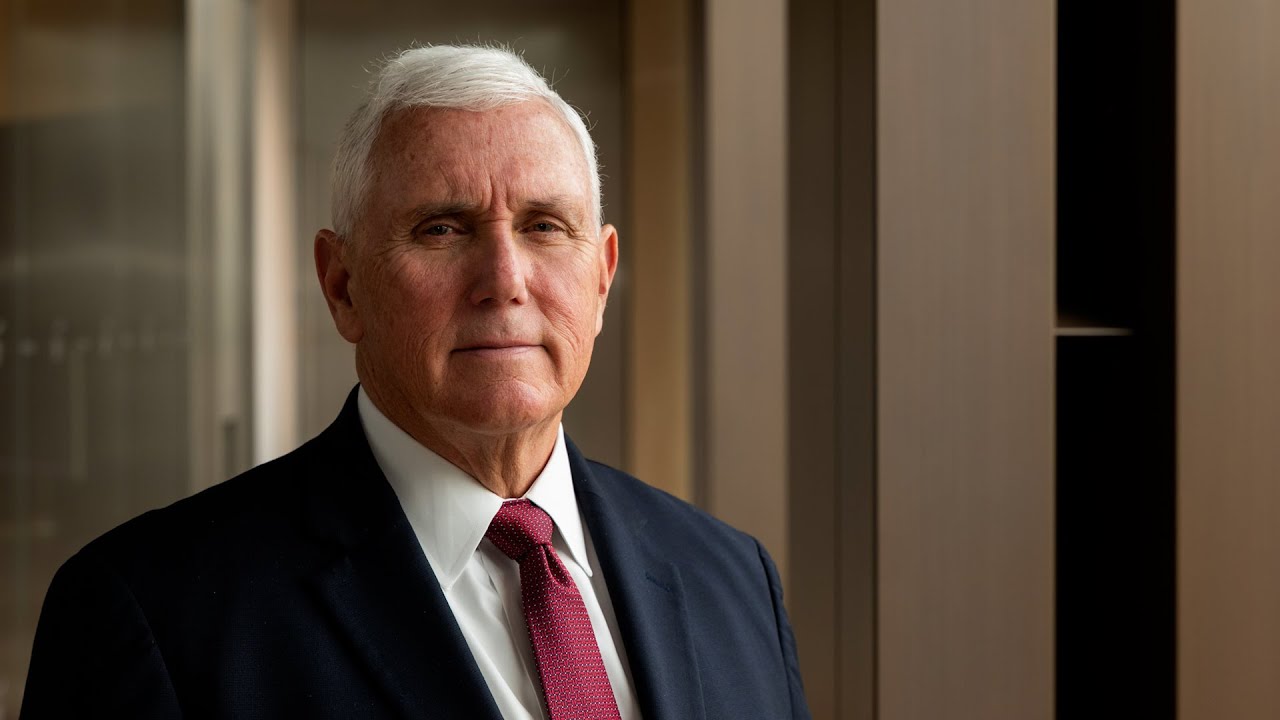

Mike Pence on U.S. Leadership and Global Strategy

Former Vice President of the United States, Mike Pence, shares his thoughts about President Trump’s framework on trying to acquire Greenland, and discusses what he…

Thought Leader: Mike Pence