Mike Pence on Leadership and the Future of the Republican Party

Former US Vice President Mike Pence looks back on the events of January 6 2021, his final days in office with President Trump and his…

Thought Leader: Mike Pence

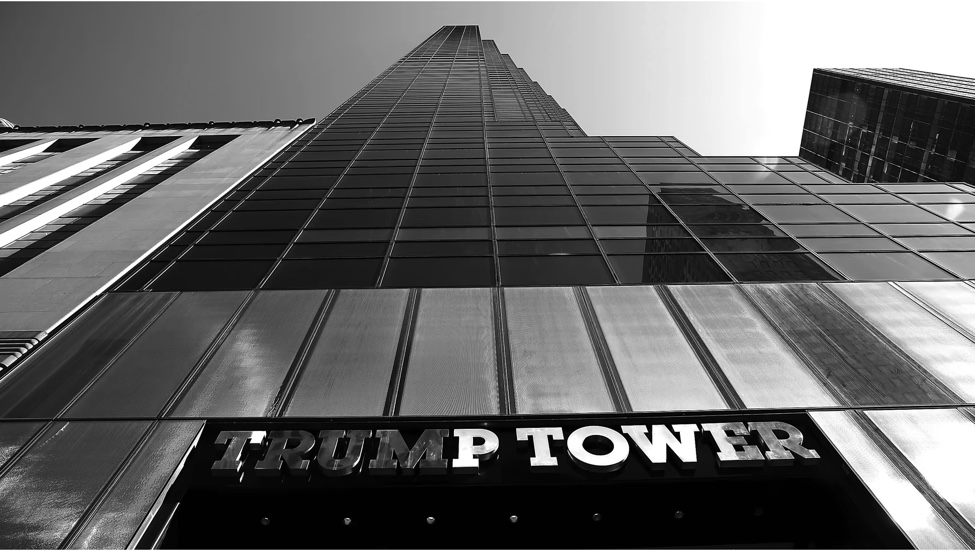

So here’s a clue as to why Donald Trump did not want anyone reading his individual tax returns. His company has just been convicted of criminal fraud for evading taxes on benefits paid to executives.

The accused was Trump’s company, not Trump himself. Nor was Trump one of the executives accused of evasion. Yet the jeopardy to Trump personally is very near and very real.

New York State’s prosecutors asserted at trial that Trump had explicitly approved the evasion scheme: “This is all part of the Trump executive compensation package. Free cars for you, free cars for your wife, free apartments for you, free apartments for your kids. Why not pay them more? Because it would cost them double to give them raises rather than give them the cars on the down-low.”

The jury’s verdicts cast light on a series of related questions that now loom large.

Why did Trump fight all the way to the Supreme Court to conceal his individual tax returns from scrutiny?

Why did Trump make such a priority of personal control of the Internal Revenue Service and the Department of Justice, given his general lack of concern with the mechanics of government?

Why was Trump willing to commit impeachable offenses in his effort to win the election of 2020, and then even more and worse impeachable offenses to hold on to power in 2021 after his defeat?

The eight years of individual tax returns (2011–19) now in the possession of the U.S. Congress must feel deeply ominous to Trump. If his 100 percent wholly owned personal company broke the rules, as has now been proved, and if Trump and his late father engaged in systematically dubious schemes to avoid inheritance and estate taxes in the 1980s and ’90s, as The New York Times reported in 2018, then it seems improbable that Trump himself abruptly turned a new leaf after 2010. A personal criminal referral could be heading his way.

But those tax issues are not of the highest public interest. Trump all along gleefully presented himself as a businessman who took every advantage, ethical or otherwise. In their first presidential debate, Hillary Clinton accused Trump of not paying any federal income taxes. “That makes me smart,” retorted Trump.

Even if tax evasion proves to be what could send Trump to prison, the highest danger to the country was something else contained within his personal and corporate tax returns.

Once in office, Trump was determined never to leave again—not only because of his crazed ego needs, but also as a matter of personal survival. As long as he held the presidency, he could resist tax scrutiny; he could benefit from the Department of Justice rule against the indictment of a serving president. But should he lose office, he would forfeit those protections and the full force of the law would bear down on him. He must not lose, no matter what.

And so he extorted the government of Ukraine—to confect a scandal against his likely presidential opponent or be denied the aid it needed to defend itself against invasion by Russia at the orders of Trump’s former business partners in Moscow. Those actions produced his first impeachment.

That scheme failed to work as hoped, although Trump and his allies never did give up entirely. After it stalled, Trump became even more frightened and desperate. He plotted to overthrow the 2020 election, first by alleged fraud, then by violence. The mob that attacked the Capitol on January 6, 2021, was sent there by then-President Trump not just to disrupt congressional proceedings but to intimidate or coerce Vice President Mike Pence into uttering magic words that Trump imagined would change the election outcome.

The jury verdicts in the Trump Organization criminal trial help us understand something that otherwise seemed murky in the January 6 plot. Even Trump had to grasp on some level that the “magic words” aspect of the plot was not very solid. Could he really expect that the 81 million people who had voted against him would quietly submit? Joe Biden won the 2020 election by the second-largest popular-vote percentage of the century, next only to Barack Obama’s in 2008. As they later testified to Congress’s committee investigating the January 6 attack, Trump’s own advisers told him that the plan was illegal, futile, and absurd.

But lurking within the January 6 plot to stop the election, I suspect, was a potentially more effective Plan B:

Create a ruckus. Get Pence into a Secret Service limo and away from the Capitol. Rapidly call the most senior senator into the presiding chair in Pence’s stead. Persuade that senator, Charles Grassley of Iowa, to do Trump’s bidding and send the electoral count back to Republican-controlled state legislatures—and hope that all of this chaos produces enough doubt about the election to buy some legal impunity after 2021.

In the second-best case, Biden would enter the presidency not as the legal winner, but only after a negotiation with Trump supporters, much like the scenario for Rutherford B. Hayes in 1877. “No prosecution” would be something Trump might have aspired to negotiate for. Although Biden’s team could not have guaranteed that individual states would take no legal action against Trump, a sufficiently convulsive crisis in 2021 might have deterred any government official from trying to apply the law to Trump in 2022.

We saw something akin to that plan at work with the presidential documents Trump removed to Mar-a-Lago. He broke the law, everybody agrees. Yet when the law was belatedly enforced by the FBI, almost all Republicans fell into lockstep behind Trump—even his would-be replacement, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. This must be Trump’s most cherished wish for how other law-enforcement actions against him could be resisted. On November 15, Trump declared his candidacy for 2024. In an interview that same week, he claimed that his candidacy should protect him from federal investigation. “It is not acceptable. It is so unfair. It is so political. I am not going to partake in it.”

Trump’s hope to use the afterglow of the presidency to buy immunity is not yet crushed. But it’s not holding up either. The Mar-a-Lago investigation is unfolding. Other legal actions against Trump continue. And a New York jury has now convicted Trump’s company of crimes on the basis of evidence that, in some cases, literally bore his signature.

Since 2015, America has faced a choice: It could have a working rule of law, or it could have a Trump presidency. Not both. After much time and anguish, the Trump presidency was repudiated at the polls. Now the rule of law has returned. The man who tried to overturn the Constitution to save his job as commander in chief and avoid the law now has to meet it as defendant in chief.

Mike Pence on Leadership and the Future of the Republican Party

Former US Vice President Mike Pence looks back on the events of January 6 2021, his final days in office with President Trump and his…

Thought Leader: Mike Pence

Marc Short on U.S. Investment in Critical Minerals

Why do critical minerals matter now? Marc Short explains how U.S. investment in critical minerals fits into a broader strategy around economic security, manufacturing, and…

Thought Leader: Marc Short

Marc Short on AI Policy and the Government’s Role in Chip Technology Investment

On CNBC, Marc Short breaks down the role of AI policy and how government investment is shaping the future of chip technology. A former Chief…

Thought Leader: Marc Short