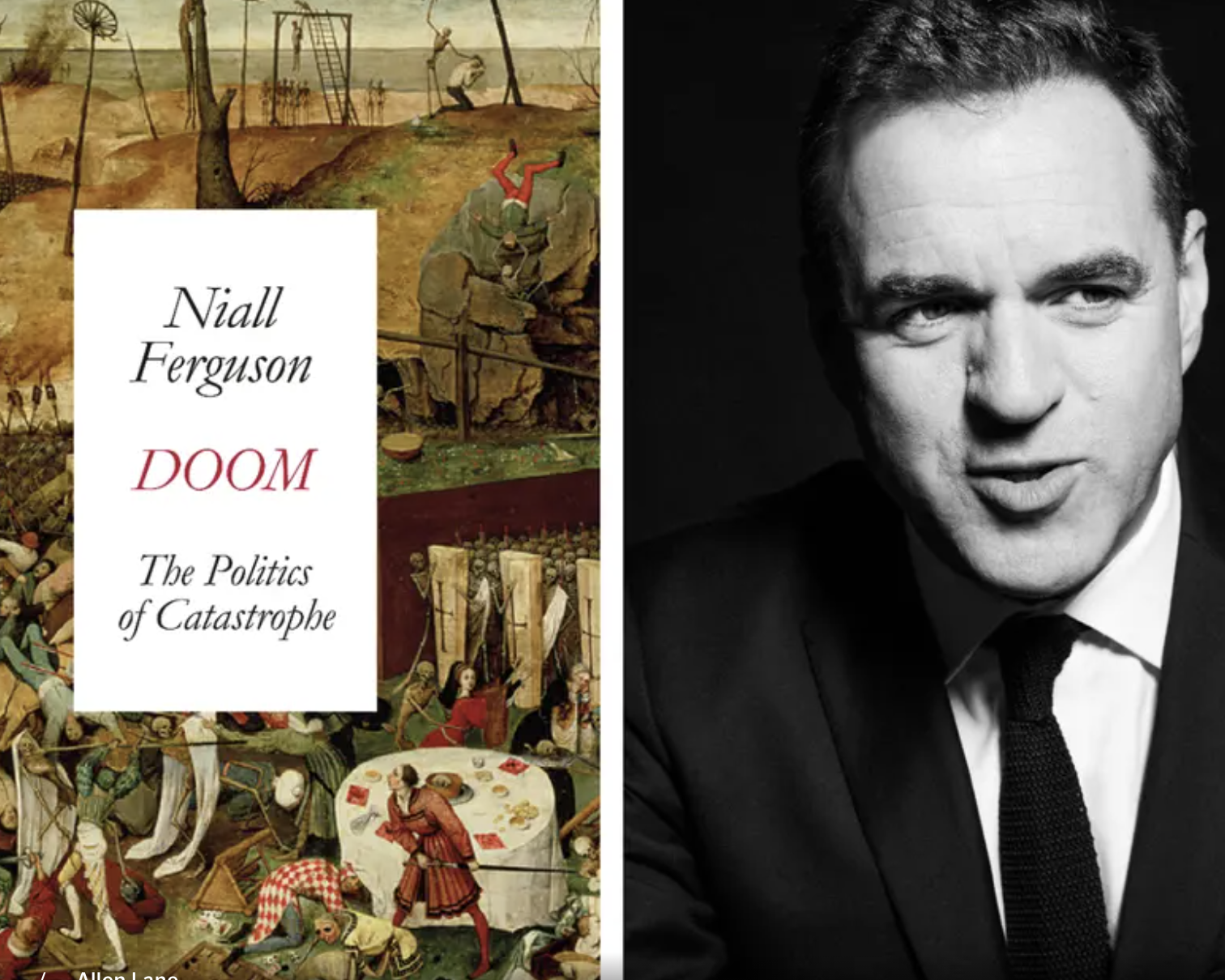

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson review

(Evening Standard) – From plagues and volcanic eruptions to the current Covid pandemic, mankind has always been faced with catastrophes.

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

Keen Footwear thought it was safe. A decade ago, long before the trade wars and the disruptions of the Covid-19 pandemic, the American company anticipated the need to limit its exposure to upheaval in the global economy.

It began abandoning factories in China that had long made its products: rugged sandals and hiking boots. It set up plants in Southeast Asia and India and then another in the Dominican Republic. In June, the company opened its newest factory, in Kentucky, an investment in the proposition now emblazoned on its shoe boxes: “American Built.”

But that branding and the company’s investment in the United States coincide with the reality that Keen, like most modern businesses, depends on access to a global supply chain for parts and raw materials. The company strives to find local suppliers to limit its vulnerability to faraway trouble, but it still moves many components around the globe to assemble its products.

That movement is now subject to an ever-changing assortment of American tariffs. Keen’s strategy to limit its dependence on any single part of the world has not been enough to spare the company from the turbulence caused by President Trump’s trade war.

On a recent morning at its factory just outside Louisville, Ky., the company’s chief operating officer, Hari Perumal, was wrestling with Mr. Trump’s latest salvo: the raising of tariffs on imports from India to 50 percent.

Mr. Perumal was also struggling to understand the details of a recently announced American trade deal with Vietnam, where Keen has a factory. And he was mulling plans to transfer the making of boot uppers from Keen’s factory in Thailand, where the tariff was 20 percent, to the Dominican Republic, where the tariff was 10 percent.

Mr. Perumal expressed confidence that Keen would manage all this without upheaval. He took comfort in having prioritized backup plans and flexibility, in contrast to the typical approach in retail — leaning heavily on one country like China to produce at the lowest cost.

Still, the exercise of having to calculate, and then recalculate, the effect of tariffs in response to Mr. Trump’s shifts was an irritating distraction.

“It changes by the day,” Mr. Perumal said. “Certainly, this kind of disruption is not good for business.”

Keen has pledged not to raise its prices this year. But the rest of the industry is already showing signs of inflation, said Matt Priest, the chief executive of the Footwear Distributors and Retailers of America, a trade association.

“President Trump’s sweeping new tariffs are a tax on every American family buying shoes during the height of back-to-school season,” he said in a statement. “These tariffs only add to the pressure at the checkout counter.”

Mr. Perumal, 58, grew up in southern India, and he now lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. He has spent his career navigating the fluctuations of global manufacturing. He first visited footwear factories in China in 1996. When he joined Keen in 2009, the company still relied heavily on Chinese factories. But as wages there rose, he began pursuing alternative places to make products.

He was intent on shrinking the distance between Keen’s factories and its customers in the United States, the source of more than half of the company’s sales.

For several years, Keen operated a factory in León, Mexico. As the pandemic spread, the local authorities halted production, prompting Keen to move the factory to the Dominican Republic. The proximity to the American market allowed Keen to double production even as the chaos of the pandemic prevented many other businesses from getting their products to customers.

But even though Keen was seasoned in adapting to crisis, it could not plan for the constant changes in trade policy delivered by the Trump administration.

Mr. Perumal had run a simulation that assumed the India tariffs would be 25 percent. That was manageable because he figured Keen’s suppliers in India would absorb some of the higher costs. Then Mr. Trump doubled the tariffs as punishment for India’s continued buying of crude oil from Russia.

“Now, that’s out the door,” Mr. Perumal said. “They can’t compensate for that level of tariff.”

For many global businesses, the latest American tariffs on India are especially unwelcome. India had beckoned as a promising alternative to China. Walmart has in recent years shifted substantial portions of its production to India from plants in China. In response to pressure from Mr. Trump to forsake China, Apple has invested heavily in shifting the production of its iPhones to India.

Mr. Perumal’s India operations already send much of their wares to Britain. Now he might also divert some of the production in India to Japan, where Keen operates stores. The few products made in India for the American market could be shifted to factories in Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam.

He was also a little less worried because of his new Kentucky factory. That plant is using machinery transferred from a facility that Keen had operated in Portland, Ore., where the company has its headquarters. Difficulty hiring workers there prompted Keen to move to Kentucky.

Louisville was already the site of its national distribution center. United Parcel Service operates an air cargo hub in the city.

In placing the new factory next door to the distribution center, Keen has reduced its carbon emissions, a key element for a brand whose marketing emphasizes its commitment to protecting the environment.

The Kentucky plant is at the core of Keen’s efforts to increase its American production from 5 percent of its global sales to 9 percent within the next 18 months. Its next milestone is 15 percent by 2030.

The factory makes boots that construction workers use. Production is heavily automated, with robotic arms placing and lifting boots onto a giant carousel, where other robots inject a gooey infusion of polyurethane that joins the upper to the sole. Every 22 seconds, a new pair are completed.

Mr. Perumal views the new plant as a useful way to serve a market that increasingly places a premium on domestic production. But he depicts domestic production as a niche, while dismissing the concept that footwear manufacturing will return en masse to American shores.

“What we are doing here, manufacturing in the United States, is not the solution to solve all these issues,” he said.

Tariffs will not force production home, Mr. Perumal said, because of differences in the price of making products in the United States versus Asia. “Where are we going to get the people?” he asked. “Are we going to find Americans willing to work for factory wages?”

He pointed at towering stacks of cardboard waiting to be folded into red-white-and-blue shoe boxes promoting the provenance of Keen’s utility boots. The boxes, which will hold boots made in Louisville, were shipped in from Cambodia. Even after the tariffs, the price was one-third what Keen would have to pay for similar packaging made in the United States.

Leather uppers made at Keen’s factory in Thailand sat in boxes waiting to be fed into the assembly line. Keen has identified a good source of leather in Mississippi. But after the cost of bringing in other needed items — shoelaces, thread, eyelets and waterproof lining, many of them made in Asia — is factored in, making uppers in the United States would be five to six times as expensive as making them overseas, Mr. Perumal said.

These sorts of details drive his interest in shifting production from Asia to the Dominican Republic, which is part of a regional trade agreement with the United States and Central American countries. Under its terms, Keen can ship components to the Dominican Republic from Asia, turn them into uppers and then export them to the United States free of duty.

That seems like a sensible adaptation, yet Mr. Perumal is under no illusions that Keen is immune to the changing variables that Mr. Trump has inserted into the global economy.

“We can only control the controllables,” he said, which appear to be a shrinking category.

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson review

(Evening Standard) – From plagues and volcanic eruptions to the current Covid pandemic, mankind has always been faced with catastrophes.

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

One reason so many are quitting: We want control over our lives again

The pandemic, and the challenges of balancing life and work during it, have stripped us of agency. Resigning is one way of regaining a sense…

Thought Leader: Amy Cuddy

Molly Fletcher: Can drive offset your burnout at work?

This piece is by Molly Fletcher. People assume that drive depletes energy. They believe that level of intensity, focus and daily effort leads to burnout.…

Thought Leader: Molly Fletcher