Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson review

(Evening Standard) – From plagues and volcanic eruptions to the current Covid pandemic, mankind has always been faced with catastrophes.

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

And so the familiar rituals of peacemaking resume. The president of the United States seeks to broker a ceasefire between two warring countries. A document, intended to be used as a starting point, is partially leaked by one side, then wholly leaked by the other side. There is controversy in the press about its provenance and significance.

The negotiators gather in a neutral location. Although there are only two combatant countries, there turn out to be many others with skin in the game. While the diplomacy continues, so does the war, each side seeking to gain leverage from military pressure.

And on it goes. And on. President Donald Trump originally set a Thanksgiving deadline (tomorrow) for Ukraine to accept a new 28-point plan for peace with Russia. A high-level U.S. delegation met with Ukrainian representatives in Geneva over the weekend to delete some of the 28 points and revise some of the others, before meeting with Russian spokesmen early this week in Abu Dhabi. However, as Trump admitted last week, the Thanksgiving deadline was never a hard one: “I’ve had a lot of deadlines, but if things are working well, you tend to extend the deadlines.” You also tend to extend them when things are not working well.

Wars are quick to start, and—unless one side achieves decisive victory on the battlefield—slow to end. The time between President Woodrow Wilson’s December 1916 peace note to the combatant powers and the end of World War I was one year, 10 months, and 25 days. The duration of the Korean armistice negotiations was two years and 17 days. Henry Kissinger’s negotiations to end the Vietnam War took three years, five months, and 24 days—and failed to secure a lasting peace between North and South Vietnam. A ceasefire was reached in the Yom Kippur War on October 25, 1973. But the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty took until March 26, 1979—five years, five months, and one day later.

This history explains why I have always treated President Trump’s promises of instant pacification in Eastern Europe with skepticism.

My position on this war has been consistent. In January 2022, I warned that war was coming. When it came, I warned that Ukraine could not hope to win a protracted conflict. In March 2022, I explained the relevant variables that would determine the war’s outcome. In September 2022, I wrote: “Ukraine’s Army Is Winning but Its Economy Is Losing,” and urged the European countries to step up their support.

One year later, I noted the spreading fatigue among American and European voters for supporting Ukraine. I consistently urged the Biden administration not to protract the war by urging a counteroffensive while slow-walking aid, but to seek to end it when Ukraine was at its strongest in late 2022 and early 2023. I have repeatedly exhorted the European governments, especially Germany, to rearm more rapidly. And I continue to push the Trump administration to seek peace through strength.

Might that last approach be close to bearing fruit? You would not think so if you relied on Western media. On November 18, Axios reported that the U.S. had “been secretly working in consultation with Russia to draft a new plan to end the war.” It is now clear that the source was the Russian negotiator Kirill Dmitriev, who had indeed met with Trump’s special envoy, Steve Witkoff, and the president’s son-in-law Jared Kushner. Dmitriev told Axios the aspects of the plan that benefited Russia. The result was a rash of press claims that America was selling out to Russian war aims.

This was deeply misleading. For one thing, Witkoff and Kushner had also been in touch with Ukrainian representative Rustem Umerov. The U.S. was also about to send its top military leaders to Kyiv. The document they intended to discuss was a work in progress, not a fait accompli. And when the full text was leaked by the Ukrainians, it was immediately apparent that it was not exactly From Russia with Love.

As I have made clear, I do not much like the 28-point draft ceasefire agreement. It is not difficult to pick holes in it. As a starting point for negotiations, nevertheless, it has much to recommend it. The version given by the U.S. delegation to the Ukrainians “confirmed” Ukraine’s sovereignty. It envisioned “a total and complete non-aggression agreement. . . between Russia, Ukraine, and Europe,” committing Russia “not [to] invade its neighbors.” Ukraine would be eligible for EU membership and would “receive short-term preferred access to the European market while this is being evaluated.” There would be substantial foreign investment in Ukraine, including from the World Bank. One hundred billion dollars in frozen Russian funds would be “invested in a United States–led effort to reconstruct and invest in Ukraine.” Europe would match this $100 billion contribution. Moreover, “all civilian detainees and hostages” would “be returned, including children.”

Crucially, Ukraine would receive “robust security guarantees.” If Russia invaded Ukraine again, “in addition to a robust coordinated military response, all global sanctions [would] be restored, [and] recognition for the new territory and all other benefits from this agreement [would] be withdrawn.”

What are the drawbacks of the deal, from Ukraine’s perspective? The size of its military in peacetime would be capped at 600,000. There would be no NATO troops in Ukraine and no chance of Ukraine joining NATO. Russia would be “re-integrated into the global economy,” and “sanctions relief [would] be discussed and agreed upon in stages and on a case-by-case basis.” Russia would be invited back into the Group of 8. Some of the unfrozen Russian assets would find their way back to Russia in a “United States-Russia investment vehicle.” Russia would have membership in a “joint U.S.-Russia Security task force. . . to promote and enforce all of the provisions of this agreement.” And all parties would receive “full amnesty for wartime actions,” including Russia’s many war crimes.

But the big sticking point for Ukraine must have been the clause stating that disputed territories—Crimea, Luhansk, and Donetsk—would be internationally recognized “de facto Russian.” Ukraine would also have to give up Slovyansk and Kramatorsk—the two major towns in the Donbas still under its control. They would become “a neutral demilitarized buffer zone internationally recognized as territory belonging to the Russian Federation.”

No doubt, all these clauses would be very hard for Kyiv to swallow. And yet, the whole thing signals a significant shift in Russian thinking, if indeed it had Russian president Vladimir Putin’s blessing (which is not yet clear).

Consider negotiations that took place in April 2022, two months after the war began. Russia demanded far more extensive “demilitarization,” including an 85,000 cap on Ukrainian troops, strict quantitative and qualitative limits on Ukrainian weaponry, and an end to Western military cooperation with Ukraine. I find it astonishing that, this time around, media coverage did not lead with Russian acceptance of a security guarantee for Ukraine. Given that Russia’s core war aim was to eliminate Ukraine as an independent, democratic state, and its ultimate goal was to break NATO, these would be high prices for Putin to pay, no matter what he got in return.

In a public address on Friday evening, President Volodymyr Zelensky said that Ukraine faced an agonizing dilemma: “either the loss of our dignity or the risk of losing a key partner,” i.e., the United States. These words implicitly accepted that Kyiv could not reject the 28-point document but would try to modify it into something more tolerable. “Yes, we are made of steel,” he said, “[b]ut any metal, even the strongest, can give way.” That is code for: We cannot fight this war for much longer.

The result of the apparently fraught U.S.-Ukrainian negotiations in Geneva was a revised 19-point plan. I have not seen this document, but it reportedly leaves a number of the hard issues—e.g., territorial cessions—to a future meeting between Presidents Trump and Zelensky. Sergiy Kyslytsya, Ukraine’s first deputy foreign minister, told the Financial Times: “Very few things are left from the original version.” According to another report, under pressure from European leaders, the questions of NATO membership for Ukraine and NATO involvement in the postwar security arrangements have also been removed. At this rate, we may end up with several documents.

My concern at this point is that these efforts to improve the terms of the deal run the risk of scuttling it altogether with the Russians. There are two related questions: How many concessions should Ukraine have to make to secure an end to the hostilities? And what will it take to persuade Putin to drop his original maximalist war aims?

In the first month of the war, I suggested that there were seven questions that would determine the duration and outcome of the war. They are worth revisiting today:

Let’s return and update the answers one by one.

Clearly, the Russians did not get to Kyiv. They are still a very long way from the Ukrainian capital, their forces stretched along a front line from the Donbas down to the Black Sea and Crimea. But they are advancing, not retreating. Their grinding offensive tactics have yielded incremental but steady gains against Ukrainian defenses.

Russian tactics now have two elements: first, launching assaults in small groups, using motorbikes and other fast vehicles to avoid Ukrainian drones; second, using long-range drones to hit Ukrainian positions. This forces Ukrainian drone units to split their attention between Russian drone operators and attacking infantry. It then lets Russian infantry get close enough to Ukrainian drone operators to kill them, slowly expanding a hole in the front line.

Ukraine currently holds three vulnerable positions: near Kupiansk in the north, around Pokrovsk in the Donbas, and around Huliaipole in Zaporizhzhia Oblast. But the Ukrainian situation is serious, not desperate. The Russians have been trying to take Pokrovsk since mid-2024. Since capturing nearby Avdiivka in February 2024, they have advanced just 25 to 30 miles. In Kupiansk, Ukraine has also largely stabilized the situation. Russia’s most serious threat is against Huliaipole which, after months of bombardment, they are now attacking. Bad weather has made Ukraine’s strike drone units less effective. Russia’s goal is to force Ukraine to choose between stabilizing the Donbas and holding Huliaipole.

Meanwhile, the air war against Ukrainian civilians continues. In the early hours of Tuesday morning, Russia hit Kyiv, killing at least six people and injuring 13 in a large-scale barrage of missiles and drones. There were also air raids in five other cities. Last Wednesday, a missile strike killed at least 39 people in Ternopil. It would be a lie to claim that these almost nightly attacks are not having an effect on civilian morale.

By contrast, Ukraine’s air war has targeted Russia’s energy infrastructure, especially its oil refineries. This has become a significant problem for Russia this year. Indeed, it may be one of the reasons why the Russians are for the first time showing serious interest in negotiating a ceasefire.

These have been significantly less effective as checks on the Russian war machine than American and European policymakers originally promised. Not only has Russia been able to keep exporting substantial quantities of oil and gas, but European countries have continued to sell goods to Russia in large quantities via third countries such as Kyrgyzstan.

But things are changing. Last month, the United States imposed sanctions on two of the “Big Four” Russian oil firms. Given Biden-era sanctions on the other two, this means all of Russia’s large oil firms are now under significant U.S. sanctions. The EU has mirrored these sanctions, imposing further ones on a Russian-owned refinery in India.

If the United States now imposes secondary sanctions on Indian and Chinese buyers of sanctioned crude, it is unlikely that they will continue to buy from Russia. Chinese and Indian refiners rely on access to the U.S. financial system for capital market needs. They dare not jeopardize this access.

Two weeks ago, the U.S. sanctioned a major Chinese import terminal half-owned by a Russian oil company, which resulted in tankers being diverted to other ports and some Chinese refineries cutting processing rates. Four Chinese state-owned oil companies, collectively responsible for 250,000–500,000 barrels/day of Russian oil purchases, have reportedly suspended purchases of seaborne crude from Russian oil companies.

If you are looking for another reason why the Russians might be serious about a compromise peace—or at least a ceasefire—look no further.

In 2022 I was focused on Russian domestic politics because Ukraine seemed united by the enemy invasion. That has changed.

On November 10, 2025, Ukraine’s National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) and Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office (SAPO) unveiled Operation Midas, a long-term investigation of corruption in the energy sector. NABU and SAPO named several suspects, including the former minister of energy, now justice minister, the former deputy prime minister, and Timur Mindich, a Ukrainian-Israeli national who is an investor in Kvartal 95, the production company Zelensky founded in 2003, and from which he draws many of his closest advisers.

Zelensky has publicly backed the Midas investigation and sanctioned Mindich, who fled the country hours before anti-corruption police searched his Kyiv apartment. Prime Minister Yulia Svyrydenko has also acted quickly to endorse the anti-corruption probes, sacking the implicated ministers as well as the entire supervisory board for Ukraine’s state nuclear company.

But this isn’t over. As the public learns more about Operation Midas, protesters could once again take to the streets, as they did in the summer, perhaps demanding the dismissal of other people thought to be connected to the scandal—including the president’s powerful right-hand man, Andriy Yermak. In turn, Yermak and Zelensky see the mayor of Kyiv, Vitali Klitschko, as a potential threat, as well as the former president, Petro Poroshenko, whom Zelensky has considered arresting.

This political mess is the reason why Ukraine needs a ceasefire soon. The unity behind Zelensky that characterized the first phase of the war is a distant memory.

Despite numerous threats, the Russians have never looked like they might use nuclear weapons, though influential people warned me in 2022 that they might if Ukraine attacked the Russian Black Sea fleet with sea drones. They did not.

There are three reasons for this. First, it is not clear what military purpose a nuclear missile would serve in such a war. Second, international condemnation and even greater isolation of Russia would be an inevitable consequence. Third, China has made it quite clear that it is opposed to any escalation to the nuclear level. And, as Putin’s quartermaster general, China calls the shots.

According to the The Wall Street Journal, “Chinese leader Xi Jinping initiated a phone call with President Trump on Monday to discuss Taiwan … [and] Ukraine” and China state media “emphasized that ‘China supports all efforts committed to peace’ ” and hopes that all parties will continue to narrow their differences and reach a fair, lasting, and binding peace agreement as soon as possible. This report was later challenged by U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, but the call clearly happened, whoever initiated it.

Why? Throughout the conflict, Beijing’s rhetoric in favor of peace in Europe has been a thin façade behind which it has unwaveringly supported the Russian war economy. China’s exports to Russia have soared in the past four years—though the increase reflects a rise in value more than volume. Is Xi suffering from peacemaking FOMO? Does Trump want him to know secondary sanctions are coming if China buys any more Russian oil? Or was the real topic of conversation a quid pro quo? We’ll tell the Russians to settle in Ukraine if you come round to cutting a deal on Taiwan, Mr. Trump, perhaps?

I was right to worry about that. House Republicans interrupted U.S. aid to Ukraine in the last year of the Biden administration, and aid has largely been wound down under Trump—though weapons sales to European countries continue with the understanding that the arms can be gifted to Ukraine.

Yet American support for Ukraine continues in other ways. The U.S. has lifted its veto on Ukraine’s use of long-range weapons to strike Russia; approved a $105 million Foreign Military Sales package to upgrade Ukraine’s Patriot air-defense systems; coordinated roughly $600 million in new U.S. military aid financed by Europe; and discussed defense-industrial cooperation between the U.S. and Ukraine, particularly in drone technology.

And that doesn’t include the military intelligence sharing that continues. So Western support for Ukraine has been more tenacious than I foresaw—another reason for Russia to want to negotiate. German rearmament has only just begun, after all. If that is done in a remotely serious way, it poses a historically resonant threat to Moscow.

In the immediate aftermath of the full-scale Russian invasion, the war had a significant impact on energy prices and inflation. Yet the costs of the war over nearly four years have mainly been borne by the Ukrainians, not by their allies. And the burden of aid to Ukraine is very unevenly distributed, with countries such as Germany and Britain contributing far more than, say, Italy and Spain. As for the benefits of the war, these have probably been greatest for China.

In that sense, the rest of the world might not lose much sleep if the war in Ukraine dragged on for another year.

But my sense is that peace is coming—or at least a ceasefire. It is not so much that Trump sincerely wants it, though it matters that he does. It is more that both combatants need it. In Ukraine’s case, that is not surprising, after nearly four years of heroic defense. But Russia also may finally be seeing that the costs of prolonging this war exceed the benefits.

This is not the end of the war. But it may be the beginning of the end. And if it is, there will really be something to be thankful for on Thursday.

WWSG exclusive thought leader Sir Niall Ferguson is one of the world’s foremost historians of economics, international relations, and global power. His incisive analysis illuminates the geopolitical forces and economic undercurrents shaping the 21st century. From great power competition to emerging security challenges, Ferguson offers unparalleled historical context and strategic insight — helping global leaders, policymakers, and business executives anticipate what lies ahead. To invite Sir Niall Ferguson to your next event, contact WWSG

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson review

(Evening Standard) – From plagues and volcanic eruptions to the current Covid pandemic, mankind has always been faced with catastrophes.

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

Time to end secret data laboratories—starting with the CDC

The American people are waking up to the fact that too many public health leaders have not always been straight with them. Despite housing treasure…

Thought Leader: Marty Makary

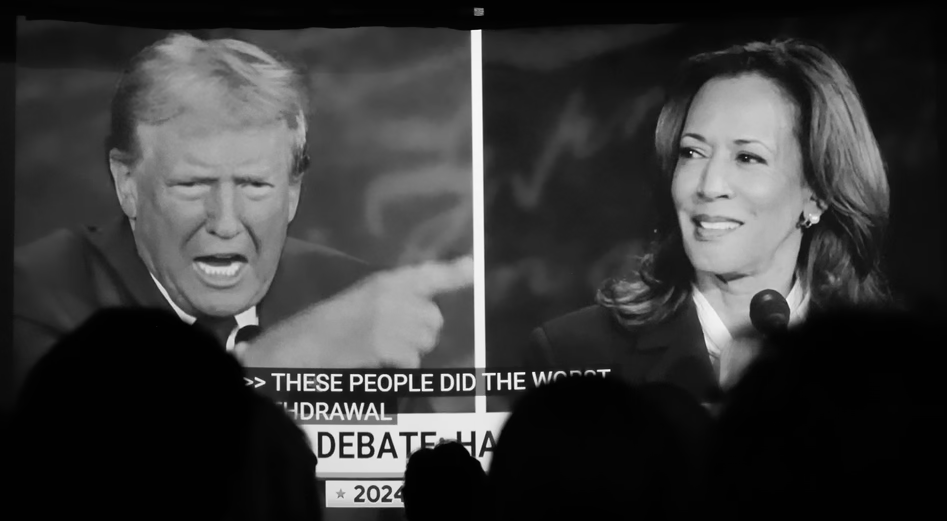

David Frum: How Harris Roped a Dope

This piece is by WWSG exclusive thought leader, David Frum. Vice President Kamala Harris walked onto the ABC News debate stage with a mission: trigger…

Thought Leader: David Frum