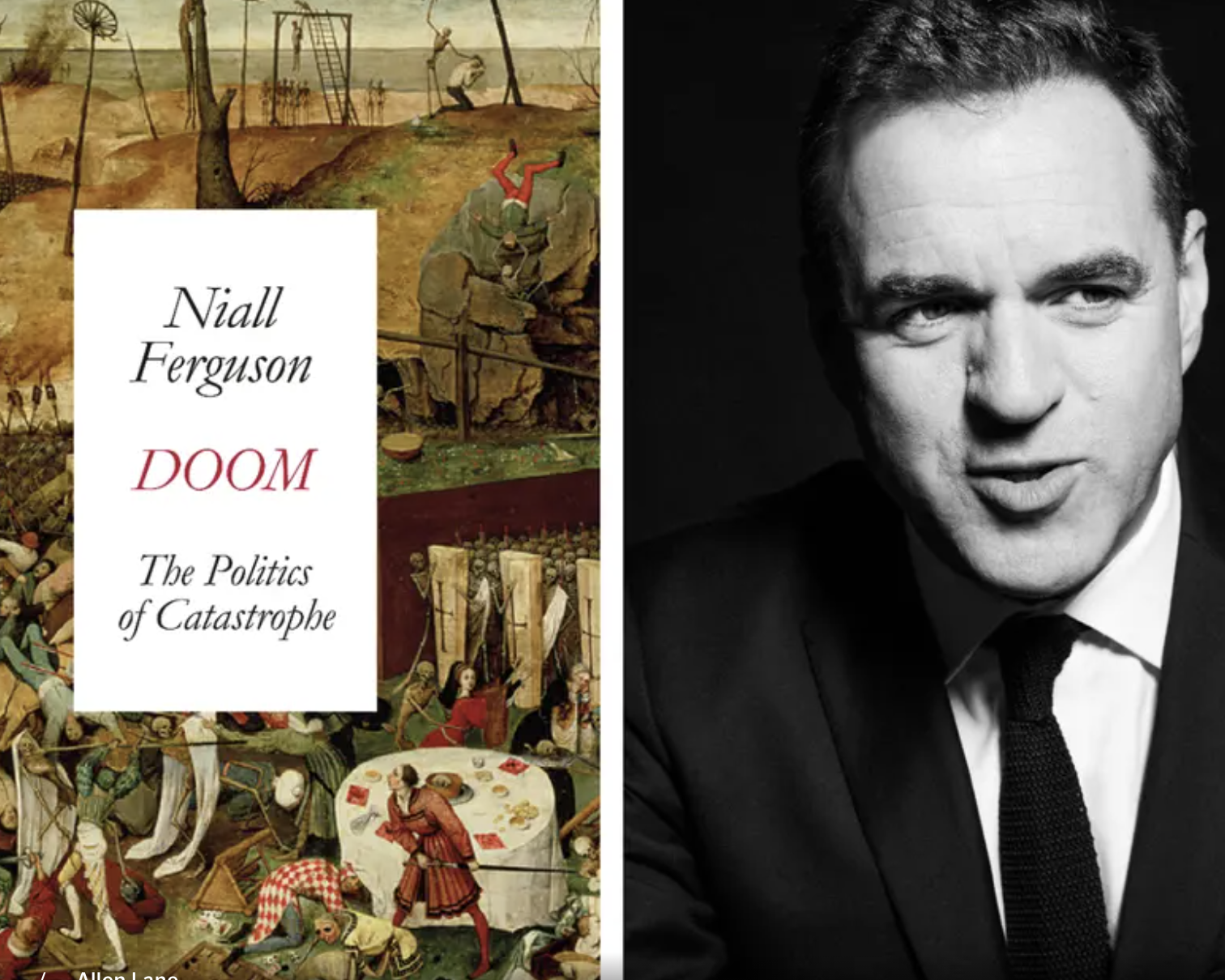

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson review

(Evening Standard) – From plagues and volcanic eruptions to the current Covid pandemic, mankind has always been faced with catastrophes.

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

A recurrent liberal fear since the 1930s has been of a fascist America — or, at least, of a transition from a republican to an imperial order. On the eve of Donald Trump’s second state visit to the United Kingdom, that fear is back on both sides of the Atlantic. “I think this is how a republic dies,” Andrew Sullivan wrote last month. “Is Trump a dictator?” asked The Guardian, answering the question in the affirmative. Lionel Barber, the former editor of the Financial Times, recently called the US president a “dictator-in-waiting”.

The killing of Charlie Kirk on Wednesday unquestionably turns the heat up further under American democracy. As the founder of Turning Point USA, Kirk was an indefatigable advocate for Trumpian conservatism, who worked tirelessly and cheerfully to counter the “woke” consensus on college campuses. I met him at a dinner in Los Angeles last May and was won over by his obvious sincerity and integrity and his commitment to his Christian faith as much as to conservative politics. Kirk’s assassination has sent a shock wave through the generation of young, mostly male right-wingers he inspired.

“Classical liberalism and moderate conservatism in America definitively kicked the bucket yesterday,” one of them wrote to me on Thursday morning. Assuming the gunman’s motive, he said: “Charlie spent his whole life preaching and living the moderate option. Yet the left murdered him as an extremist anyway … America has indeed breached a Turning Point. I fear that from Charlie’s blood sprang 10,000 Francos yesterday. The left sowed the Years of Lead. They will reap the Storm of Steel.”

In a television address, Trump hailed Kirk as a “patriot” and a “martyr for truth and freedom”. “For years,” Trump said, “those on the radical left have compared wonderful Americans like Charlie to Nazis … This kind of rhetoric is directly responsible for the terrorism we’re seeing in our country today.” It was predictable that the left would immediately turn this on its head, accusing Trump of instrumentalising Kirk’s killing, as Hitler used the February 1933 Reichstag fire, to move America a step closer to dictatorship.

My benchmark, ever since Trump emerged as a plausible presidential candidate ten years ago, is Buzz Windrip. In It Can’t Happen Here(1935), a bombastic Democratic senator — Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip, modelled on Huey Long, the populist Louisiana governor — is elected president, overthrows the constitution, and institutes something a lot like an American Nazi regime, complete with paramilitary thugs (“Minute Men”), a Goebbels-like sidekick, and “Corpo” economics. Resistance comes only from a motley band of conservative Republicans and libertarians like the Vermont newspaper editor Doremus Jessup, who is the book’s hero.

American literature has produced better-written fascist dystopias: Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) and Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America (2004), to name just two. The Cold War produced the alternative dystopia of a Stalinist totalitarianism. Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953) describes a world where the state has banned all books and routinely burns any that it finds. But Buzz Windrip is the Donald Trump of liberal nightmares.

Sullivan likens Trump to “a wild boar — psychologically incapable of understanding anything but dominance and revenge, with no knowledge of history, crashing obliviously and malevolently through the ruined landscape of our constitutional democracy”, because he “cannot tolerate any system where he does not have total control”.

Trump may not have gone full Windrip in his first term, Sullivan concedes, but in his second he has been unleashed. He can and does go after domestic opponents, from law firms to bureaucrats to journalists and judges. He imposes tariffs with “zero constitutional or legal authority”. He has pardoned “violent rioters, insurrectionists, and corrupt pols on the take,” assaulted the autonomy of universities, ended free-speech protections for non-citizens, and mobilised “armed, masked, anonymous men and women” to round up and deport suspected illegal immigrants.

Kim Lane Scheppele, a professor of sociology at Princeton University, echoes Sullivan’s alarm, citing Trump’s mobilisation of the national guard to clamp down on urban crime as further evidence that America is on the road to dictatorship. The US is “collapsing into some form of authoritarianism”, the Harvard political scientist Steve Levitsky told The Guardian, where “there’s widespread abuse of power that tilts the playing field against the opposition” so “you would not call that a full democracy”.

Specific incidents — the FBI raid on the home of John Bolton, Trump’s former national security adviser turned critic, the replacement of the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ commissioner with a Trump ally, the firing of the Federal Reserve governor Lisa Cook — are grist to the mill of such critics.

And yet there is a danger of impressionism in much of this commentary. The Guardian solemnly told readers of “a giant banner” draped over the labour department building “showing Trump glaring out over Washington DC above the slogan ‘American workers first’”. Wait, banners equal fascism? Barber recoils from “the $200 million state ballroom which Trump has ordered” to replace the east wing of the White House. But where in the constitution is there a prohibition on ballrooms?

Everyone suffering from Windrip Syndrome needs a reminder of what fascism was. In Italy, following the murder of the Socialist deputy Giacomo Matteotti in 1924 (almost certainly ordered by Mussolini), political opposition was suppressed. The likes of the Leninist Antonio Gramsci were imprisoned. Newspaper editors were required to be fascists, and teachers to swear an oath of loyalty. Parliament and even trade unions continued to exist, but as sham entities, subordinated to Mussolini’s dictatorship.

German National Socialism emerged from the Depression, as opposed to the sustained expansion the US has experienced in the past decade. It was explicitly revolutionary — the stated goal was to overthrow the Weimar system and create a racially pure Volksgemeinschaft. Party agencies systematically used violence against opponents. Soon after Hitler came to power in 1933, the new regime began exerting direct control over the civil service, the media, the military and the police. Rearmament became the goal of economic policy and war the goal of foreign policy. Antisemitism was a core feature. Above all, the Third Reich was from the outset a lawless regime. Just think of the arrests without trial — 26,000 people were in “protective custody” as early as July 1933 — and the summary executions, beginning with the Night of the Long Knives in June 1934, when at least 85 people were murdered.

Another historical reminder: the “imperial presidency” long predates Trump. Franklin Roosevelt’s critics saw the New Deal as a power grab by the executive branch. Richard Nixon’s Democratic critics made similar arguments in 1973. As Jack Goldsmith of Harvard and the Hoover Institution has argued, there has been a sustained “escalation of power grabs” by the presidency throughout this century, “aided by … substantial delegations of power from Congress and an approving Supreme Court”. George W Bush greatly enlarged the power of the US national security state after the 9/11 attacks. Barack Obama used executive orders for “largescale and sometimes legally dubious policy initiatives” and used “legally dubious threats to yank federal funds from universities” to force changes to their rules on sexual assault and harassment — changes that had many malign consequences.

Joe Biden abused the presidential power of pardon for the benefit of his own errant son, among others. He also extended the Supreme Court’s unitary executive case law to fire the statutorily protected commissioner of the Social Security Administration. He purged Trump appointees from arts and honorary institutions and administrative roles. And, of course, the Biden administration had no qualms about waging or encouraging “lawfare” against political opponents, not least Trump himself.

In recent months, there has been a crescendo of complaint about the Trump administration’s alleged undermining of the Federal Reserve’s independence. However, as the Treasury secretary Scott Bessent has argued, it is the Fed that has been overreaching in the years since the global financial crisis. A “gain-of-function monetary policy experiment” (quantitative easing) boosted wealth inequality much more than growth, then caused a nasty bout of inflation in 2022, and may end up costing taxpayers billions. The Fed has overreached on regulation, too. And its politicisation — judged by the political donations of Reserve Bank directors — dates back ten years.

Yes, since his second inauguration Trump has cited emergency powers in about three dozen orders and memoranda. But both Obama and Biden did the same thing; they just did it more slowly. In any case, the law courts are grappling with close to 400 cases involving the Trump administration. According to the website Just Security, of 389 cases, none has been closed in favour of the plaintiff, 25 have been blocked, 79 blocked temporarily, 20 blocked pending appeal, 20 temporarily blocked in part; 39 have had a temporary block denied in part or wholly, 34 are pending appeal, 147 are awaiting a court ruling, 22 have been closed, and just seven have been closed or dismissed in favour of the government. This is Trump’s fifth year in government. I can assure you, this was not how German lawcourts worked in 1938.

Steve Cohen, a Democrat congressman from Tennessee, has a website that tracks what he calls the Trump administration’s “harmful executive actions”, from the closure of USAID to the sending of threatening emails to federal workers. The problem here is that Cohen conflates actions that are open to legal challenge and actions that are matters of policy he doesn’t like. Harvard and Hoover’s Goldsmith estimates that in about four dozen cases, the Trump administration has simply accepted court rulings against it, either by not appealing them or by not pushing further after losing in courts of appeals.

As Jed Rubenfeld argues, the cases heading to the Supreme Court are doing so precisely because they are far from open-and-shut. The International Emergency Economic Powers Act may not be a secure basis for Trump’s reciprocal tariffs, as it confers on the president the power to “regulate” imports, not the power to tax them. That was the view of the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. But Section 338 of the Tariff Act of 1930 (the infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act) empowers the president to impose tariffs of up to 50 per cent on any country that is placing “any burden or disadvantage” on US commerce. So the Supreme Court may side with Trump.

The justices may rule against Trump in the case of Lisa Cook, the fired Fed governor, as it seems unlikely that a majority of them will accept the unproven allegations of mortgage fraud as sufficient “cause”. They may also rule that the administration was acting illegally when it sank a boat allegedly carrying drug-smuggling members of the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua, or when it deported gang members on the basis of the Alien Enemy Act. But the justices may well back Trump on his right to send the National Guard to Los Angeles and Washington. There are precedents for sending in the military to protect government officials carrying out their duties — in this case agents of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

As the Harvard Law School professor Noah Feldman has pointed out, sooner or later the Supreme Court will have to make its mind up on these cases. Only if it calls every one of them in the administration’s favour will we need to start worrying that the separation of powers has stopped working.

In the same way, it is too early to write Congress off as a mere rubber stamp for the White House. The Republican majorities in the Senate and House are wafer-thin. The economy is palpably slowing, partly because of tariffs, partly because of the drastic reduction in immigration. Inflation is still well above the Fed’s 2 per cent target. Voters are thermostatic: they wanted immigration restrictions back in November but are squeamish about deportations now that they see employees and neighbours rounded up and expelled. Despite the Democrats’ tanking approval and voter registrations, the GOP could still lose the House in the midterms in November next year.

There are informal checks on presidential power, too. The chief executives of some of the biggest tech companies seem embarrassingly eager to kiss Trump’s ring in return for minimal AI and crypto regulation, but not everyone is so sycophantic. Trump has plenty of vocal critics on both Wall Street and Main Street. The same is true of the media. It’s hard to shut up the US press corps, and the internet has made the media even more unruly than in the past. American generals seem unlikely to support a US monarchy as there remains a very strong culture of military loyalty to the constitution. As for the 1.3 million practising lawyers in the US, they all have a vested interest in preserving the rule of law. It’s their livelihood.

The prelude to dictatorship is often civil war or anarchy. Americans may be polarised, but they are not at war with one another. I say this even after recent events that seem calculated to increase the risk of civil strife: not only the assassination of Charlie Kirk but also the fatal stabbing of Iryna Zarutska, 23, a Ukrainian refugee, in Charlotte, North Carolina, last month. The man accused of killing her, an African American named Decarlos Brown, 34, had previously been convicted of robbery with a dangerous weapon, breaking and entering, and larceny. After the attack, he said simply: “I got that white girl. I got that white girl.”

If a hostile foreign power sincerely wished to destabilise American politics, the killings of Charlie and Iryna would be perfectly crafted to that end — one crime exacerbating political division, the other racial mistrust.

As in the 1930s, when Sinclair Lewis dreamt up Windrip, there are many in the 2020s who are emotionally overinvested in the idea of an American descent into fascism. It would be naive to dismiss the fear that — especially in the febrile atmosphere occasioned by two brutal murders — the presidency will grow yet more powerful relative to the other branches of government. But the serious student of history knows that the United States today is a very long way from Italy in 1927 or Germany in 1938. And now, as then, it seems much more likely from a geopolitical standpoint that the US will end up in conflict with the truly authoritarian regimes than fighting alongside them.

There is nothing like fighting real fascists to rekindle the American love of liberty. It is a love personified by Charlie Kirk, who dedicated his life to debate and died with a mic, not a knife, in his hand.

WWSG exclusive thought leader Sir Niall Ferguson is one of the world’s foremost historians of economics, international relations, and global power. His incisive analysis illuminates the geopolitical forces and economic undercurrents shaping the 21st century. From great power competition to emerging security challenges, Ferguson offers unparalleled historical context and strategic insight — helping global leaders, policymakers, and business executives anticipate what lies ahead. To invite Sir Niall Ferguson to your next event, contact WWSG.

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson review

(Evening Standard) – From plagues and volcanic eruptions to the current Covid pandemic, mankind has always been faced with catastrophes.

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

Time to end secret data laboratories—starting with the CDC

The American people are waking up to the fact that too many public health leaders have not always been straight with them. Despite housing treasure…

Thought Leader: Marty Makary

Molly Fletcher: Can drive offset your burnout at work?

This piece is by Molly Fletcher. People assume that drive depletes energy. They believe that level of intensity, focus and daily effort leads to burnout.…

Thought Leader: Molly Fletcher