Time to end secret data laboratories—starting with the CDC

The American people are waking up to the fact that too many public health leaders have not always been straight with them. Despite housing treasure…

Thought Leader: Marty Makary

This piece is by WWSG exclusive thought leader, Niall Ferguson.

As President-Elect Donald Trump prepares to seek a negotiated settlement to the worst European war since 1945, he confronts in Russia a counterparty with real bargaining power. Over the three decades since the end of the Cold War, Russia has become a serious international player, with greater military-industrial capacity than Europe and one of the world’s largest land armies, as well as the world’s second-biggest nuclear arsenal. Russia has also been coordinating its Ukrainian war effort with Iran, China, and North Korea, creating in effect a New Eurasian Axis.

The peace talks are set to begin at a time when, despite American and European military assistance to Kyiv, Russian forces are advancing westward and Ukrainian resistance is close to its breaking point. As Ukraine’s former foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba told the Financial Times recently, “If it continues like this, we will lose the war.”

Although many in the Republican Party question the fact, the United States has a major interest in Ukraine’s survival and a durable settlement. With the biggest population of any Eastern European country aside from Poland, Ukraine has significant mineral resources and is a major agricultural exporter. Though impoverished by war, the country has also developed an impressive defense-tech sector.

If Russia succeeds in its aggression, the Baltic states would be next in line. Russia may also have interfered in Romania’s recent election in an attempt to install a pro-Kremlin president. In short, there is no reason to expect Russian ambition to halt at Ukraine’s western borders. Trump has expressed skepticism about the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, but the best way to prevent Moscow from testing the treaty’s Article 5 mutual-defense clause is to preserve an independent Ukraine. Even so, the U.S. negotiating team must learn from history that Russia does not negotiate in good faith, but sees diplomacy as a way to freeze rather than resolve a conflict, to build military leverage, and to split allies.

If the U.S. is to end the Ukraine war in a way that satisfies American interests, it must counter Russia’s strategy and build military, as well as economic, leverage over Russia. This will require not just surging aid to Ukraine and tightening the sanctions regime, but also imposing costs on Russia and its allies across Eurasia, including in Europe, the Middle East, and the Pacific region.

The process will be tense and risky. Washington must ensure that Kyiv avoids the trap of a mere cease-fire and reaches a settlement that can endure. In America’s favor is that Russian President Vladimir Putin’s position has been weakened by the sudden collapse of his client Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria. That is a weakness Trump must now exploit.

Western diplomats tend to view fighting and talking as entirely distinct; when they begin negotiations, they typically set out a minimum viable position first and then make preemptive concessions as tokens of good faith. The Russian tradition of strategic thinking approaches diplomacy quite differently. From the Soviet Union’s earliest years, Moscow viewed warfare and political action, including diplomacy, as unitary. Negotiations are just another tool to improve one’s political position; the objective, as with military operations, remains the enemy’s subjugation, or at least its exhaustion.

Moscow’s negotiators seldom see talks as a route to a genuine, durable settlement, at least not initially. Instead, by controlling the pace of negotiations, Russian diplomats seek to wear down their adversaries psychologically. They are also likely to try to divide the U.S. from its allies.

This approach has a clear Cold War precedent. In Korea and Vietnam, the Soviet Union and its partners stalled negotiations, insisting on the most pedantic points, accusing the U.S. of bad faith, and starting with outlandish demands that, if the U.S. were to satisfy them, would have amounted to capitulation. After the mid-1960s, the Soviets understood the extraordinary risks of a general war with NATO.

Exploiting its relative strength in the mid to late ’70s, the U.S.S.R. encouraged its Warsaw Pact satellites, particularly East Germany and Poland, to negotiate directly with their West German neighbors, while it continued to back West European Communists in Italy and elsewhere, and to intensify its military threat. Moscow thus aimed to compartmentalize détente, hoping that a series of bilateral contacts in Europe would break the Atlantic alliance’s cohesion.

The U.S. response carried clear risks. The Reagan administration’s military buildup directly challenged Soviet offensive conventional forces, even as expanding U.S. nuclear deployments triggered large-scale protest movements in Europe. Fortunately, the political balance shifted in Germany when Helmut Kohl became chancellor in 1982, restoring the alliance’s cohesion, while the appointment of Mikhail Gorbachev as Soviet leader in 1985 ushered in an abnormal period in which Moscow made unparalleled concessions abroad in the hope of expediting reform at home. (Gorbachev may be remembered fondly in the West; he is reviled in Russia today.)

From the Russian viewpoint, its war against Ukraine is one aspect of a broader war with the West. Ukrainian resistance would not have lasted this long without NATO support, making NATO cohesion vital to Ukraine’s future. Russia’s negotiation strategy will prioritize breaking this solidarity.

Of course, this has been Russia’s strategy since 2014. The Minsk process, a slap-dash negotiation effort midwifed by Franco-German ambition, ensured that Ukraine’s status remained in limbo. Russia’s strategy failed only because Ukrainian society remained firmly pro-Western, encouraged by the economic opportunities the European Union offered, and deterred by the calamitous Russian management of its proxy statelets in the Donbas region. But Moscow did succeed in freezing Ukraine-NATO discussions and hampering Kyiv’s military buildup.

A renewed Minsk agreement is practically impossible, because Russia’s 2022 invasion made it an unmistakable belligerent in its own right; by the same token, its annexation of Ukrainian territory has rendered the concept of “autonomous zones” irrelevant. So what deal should the new Trump administration aim for?

On the campaign trail, Trump gave the impression that he could end the war virtually overnight. A more realistic goal would be for a cease-fire by March of next year.

Severe military attrition has created an incentive for Putin to enter into talks. Despite battlefield advances, Russia’s manpower losses are running as high as 45,000 a month. At a minimum, the Russian military needs a pause to reconstitute its forces. Particularly if Ukraine can hold its current positions in the east for the next few months, Russia is likely to join talks.

That will be the easy part. The challenge for U.S. policy is not simply to bring Russia and Ukraine to the table but to keep them there—and ensure that a cease-fire means more than merely a tactical pause for Moscow.

Because Putin has repeatedly questioned the legitimacy of President Volodymyr Zelensky’s government, the Kremlin may open by demanding bilateral negotiations with the West and rejecting Zelensky’s participation. If, in its opening months, the Trump administration surges aid to Kyiv, especially to enable Ukrainian strikes on Russian soil with Western weapons, that should overcome Moscow’s resistance to Ukrainian participation.

Russia will doubtless present a series of extreme demands. These are likely to include: a freeze on Ukrainian talks about NATO membership; neutrality written into the Ukrainian constitution; special rights for Russian-speakers; the removal of restrictions on the Russian Orthodox Church (a de facto arm of Russia’s intelligence apparatus in Ukraine); acceptance of responsibility for the “Donbas genocide” that Russia used as a casus belli; and withdrawal from territory in the Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia oblasts.

No Ukrainian president could accept these demands. Russia understands this—its goal will be to paint Ukraine as intransigent, providing a pretext to stall talks. At the same time, Russia will almost certainly undermine any cease-fire by exploiting weak monitoring and enforcement mechanisms to harass Ukrainian forces. This will demoralize war-weary Ukrainians, desperate for a lasting cease-fire and final settlement. Russia may also try to manipulate the talks by halting its bombardment of Ukraine’s energy sector as a phony goodwill gesture and demanding that the U.S. prevent Kyiv from striking Russian soil in return. This would play to Russia’s tactical advantages in the frontline fight.

Russia is also sure to demand major restrictions on Ukrainian military capacity and capability. For Kyiv, resisting disarmament will be vital for the country’s future. Despite shortages and wartime disruption, Ukraine’s defense industry has developed at a remarkable rate. Kyiv has already concluded a series of defense pacts across Europe, some of which include direct funding for Ukrainian industry. But Ukraine cannot reap the full benefits of these agreements until it can safeguard its industry from bombardment and re-equip its armed forces.

To achieve a meaningful settlement, the U.S. must build leverage in a much broader way, linking Russia’s position in Ukraine to other interests. Four steps make sense: increased pressure in the Middle East, disruption of Russia’s Eurasian partnerships, explicit U.S. acceptance of European-led security initiatives, and exploitation of Russia’s reliance on Chinese economic support.

Recent events have created useful opportunities on the first score. Russia’s position in the Middle East and Africa has become a vulnerability. By backing Assad and gaining air and naval bases in Syria, Russia built a military bridge through Crimea, the Levant, and Libya, and into Africa, where Russian mercenary groups control valuable mineral deposits and protect Russian-owned assets. But Russia’s position in the Middle East and Africa suddenly looks weak. Russia needs Iran in order to sustain its war effort in Ukraine and evade Western sanctions; so the more Israel can damage Iran, the less fruitful Moscow’s ties to Tehran will be. And without an ally controlling Syria, Russia will struggle to sustain its influence in Africa.

The U.S. can also disrupt Russia’s partnerships with North Korea, Georgia, and Belarus. North Korean artillery shells have become essential to Russia’s war effort, and North Korean troops are now fighting Ukrainian forces in Kursk oblast. That military support requires a response: The new Trump administration should revert to its prior “maximum pressure” policy, to increase the cost to Pyongyang of its aid for Moscow. The U.S. should lean on Georgia, too, through sanctions justified by evidence of fraud in the recent election that shifted the country back toward Russian-proxy status. Similarly, U.S. support for the Belarusian opposition to President Alexander Lukashenko’s regime can be stepped up.

For its third step, the U.S. should consider including some European powers in the opening rounds of Ukraine talks. Most relevant would be Poland, Finland, and the Baltic states, which have shown their military capabilities and commitment to Ukraine’s defense. Any future security guarantees for Ukraine are bound to involve these states, as U.S. troops certainly will not be involved. And the most effective leverage on Russia today may be accelerated European rearmament.

Finally, the United States must get serious about China’s huge support for the Russian war effort. Trump clearly intends to resume his trade war with China. This time around, that effort should target Chinese firms involved in the Russian military machine with immediate secondary sanctions.

Wars are easy to start yet hard to stop. But combining these four elements with sustained military and economic support for Ukraine will give Washington a chance to keep Russia at the negotiating table. No one entrusted by Trump with negotiating an end to the war in Ukraine should expect overnight success. The challenge will be to overcome Russia’s tried-and-tested method of cynically exploiting negotiations to gain military advantage.

The beginning of talks should mean not the end of military and economic pressure but the reverse. The new Trump presidency will be a crucial moment for the U.S. and its allies to lean harder—not just on Russia, but on the Eurasian Axis as a whole.

Time to end secret data laboratories—starting with the CDC

The American people are waking up to the fact that too many public health leaders have not always been straight with them. Despite housing treasure…

Thought Leader: Marty Makary

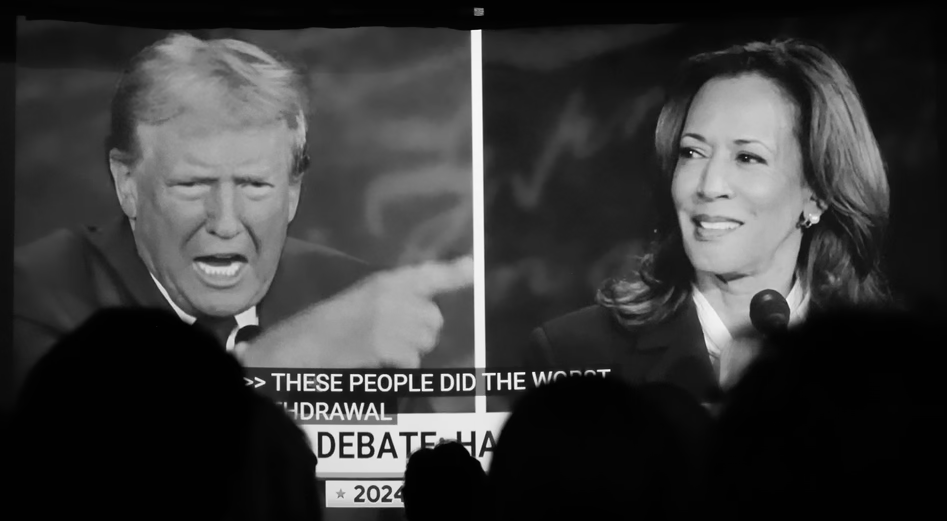

David Frum: How Harris Roped a Dope

This piece is by WWSG exclusive thought leader, David Frum. Vice President Kamala Harris walked onto the ABC News debate stage with a mission: trigger…

Thought Leader: David Frum

Michael Baker: Ukraine’s Faltering Front, Polish Sabotage Foiled, & Trump vs. Kamala

In this episode of The President’s Daily Brief with Mike Baker: We examine Russia’s ongoing push in eastern Ukraine. While Ukrainian forces continue their offensive…

Thought Leader: Mike Baker