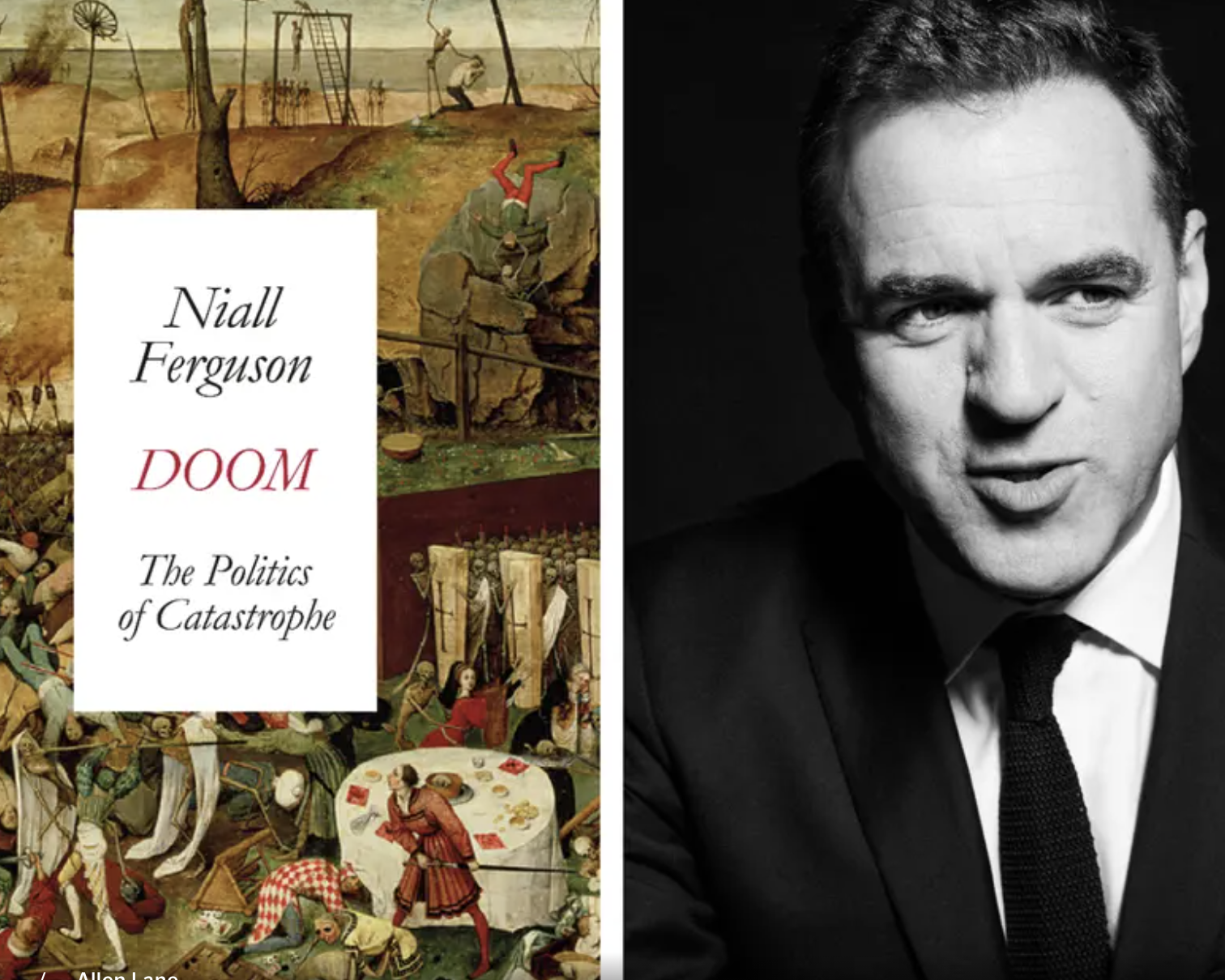

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson review

(Evening Standard) – From plagues and volcanic eruptions to the current Covid pandemic, mankind has always been faced with catastrophes.

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

Happy Constitution Day—or, to be precise, Happy Constitution and Citizenship Day.

It was on this day, in 1787—so 238 years ago—that the delegates to the Constitutional Convention signed the republic’s foundational document in Philadelphia. Congress designated September 17 as “Constitution Day and Citizenship Day” in 1952. This was the culmination of a campaign that had begun in World War I In 1917, when the Sons of the American Revolution formed a committee, whose members included future president Calvin Coolidge, to promote Constitution Day.

In 1939, on the eve of another world war, the day was rebranded as “I Am an American Day,” complete with a song of that name by Gray Gordon and his Tic-Toc Rhythm.

(You see, there’s nothing new under the sun.)

The chorus line was “I am an American, I’m proud of my liberty”—so essentially Lee Greenwood for the big band era.

In March 1941, Rep. Thad Wasielewski of Wisconsin recognized Mrs. Clara Vajda, a Hungarian immigrant, as the founder of Citizenship Day, which had by then become a celebration of “all those who, by coming of age or naturalization, have attained the status of citizenship.”

Since learning that, I must say, as a naturalized American citizen, I regard today in a new light. It is a reminder of the vital importance in American history of the legal path to citizenship, and the dangers—which have become so glaringly apparent in recent years—of blurring the distinctions between illegal residents, lawful residents, and full citizens.

In 2005 it was enacted that, each year on this day, all publicly funded educational institutions, and all federal agencies, should provide educational programming on the history of the Constitution.

Judging by the experience of the subsequent two decades, a single day’s instruction on this vital subject is not enough.

Well, we don’t need that kind of government mandate here at the University of Austin. We don’t just think about the Constitution once a year. We think about it literally every day, for the simple reason that our own governing document is deliberately modeled on it. That’s the reason we have a legislative branch (the board of trustees), an executive branch (the president, chancellor, provost and other officers), and a judicial branch (the adjudicative panel). That’s the reason we have a bill of rights, which spells out not only our freedoms, but also our responsibilities.

We adopted this system of governance because we believed that the collapse of academic freedom and academic standards that we beheld in nearly all established universities over the decade or so before our foundation had its roots, at least in part, in defective structures of governance.

Like the U.S. constitution, ours has already been amended several times as we have learned by experience. But I believe experience has already revealed it to be a functioning document, confirming that there are real checks and balances on the executive branch, and therefore real protections for the rights of professors and students.

This afternoon, however, I wish to address a broader question about the relationship between our start-up, upstart college and the republic under whose laws we operate.

It must be the case that even the most perfectly constituted university would be unable to uphold the pursuit of truth and academic excellence if it were located in a country with an illiberal political system.

We are far from the first academic institution to adopt Immanuel Kant’s sapere aude—“dare to think” as a tagline. It was the motto of the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, which was established under Joseph Stalin. I think we can be confident that its faculty and students were very careful indeed about what they thought.

The top German universities in the 1920s were universally recognized as the world’s best. They dominated the lists of Nobel Prize winners in the sciences. Yet their excellence did not protect them after Hitler came to power in 1933. Indeed, as I argued in a previous talk here, German professors and students at institutions such as Marburg, Heidelberg and Tübingen enthusiastically embraced National Socialism before and after 1933.

Their Faustian pact with Hitler’s illiberal ideology has been mirrored in our own time by the readiness of a generation of academics and academic administrators to make a similar pact with such illiberal ideologies as the various schools of “grievance studies,” deliberately terminating the teaching of western civilization in an orgy of “decolonization” that culminated in the toxic celebration of barbarism on many American campuses after October 7, 2023.

But what, some of our critics now say, if the republic itself is in danger of a fate similar to that which Germany suffered in the 1930s?

A recurrent liberal fear has been of a fascist America—or, at least, of a transition from a republican to an imperial order. “I think this is how a republic dies,” my old friend Andrew Sullivan wrote last month. “Is Trump a dictator?” asked the London Guardian on September 1, answering the question in the affirmative. Lionel Barber, the former editor of the Financial Times, recently called President Trump a “Dictator-in-waiting.”

The murder of Charlie Kirk at Utah Valley University has unquestionably turned the heat up further under American democracy. As the founder of Turning Point USA, Charlie was an indefatigable advocate for not just for Trumpian conservatism but for free speech, who worked tirelessly and cheerfully to counter the “woke” progressive consensus on college campuses around the country.

I met Charlie at a dinner in Los Angeles last May and was won over by his obvious sincerity and integrity, his commitment to Christian faith as much as to conservative politics. His assassination has sent a shock wave through the generation of young, predominantly male conservatives whom he inspired.

“Classical liberalism and moderate conservatism in America definitively kicked the bucket yesterday,” one of them wrote to me on Thursday morning:

Charlie Kirk did everything the right way and was truly earnest in engaging his opponents in good faith. He was a genuine believer in everything we have been told since youth about how politics works and was our Happy Warrior in the Marketplace of Ideas.

None of that mattered. The Left blew out his jugular IN FRONT OF HIS WIFE AND KIDS. A political martyrdom live-streamed in 4K. Charlie spent his whole life preaching and living the moderate option. Yet the Left murdered him as an extremist anyways.

I cannot understate just how important this development is. America has indeed breached a Turning Point. I fear that from Charlie’s blood sprang ten thousand Francos yesterday. The Left sowed the Years of Lead. They will reap the Storm of Steel.

I pray he is wrong about that.

In a nationwide television address, President Trump himself hailed Charlie as a “patriot” and a “martyr for truth and freedom.” “For years,” Trump said, “those on the radical left have compared wonderful Americans like Charlie to Nazis … This kind of rhetoric is directly responsible for the terrorism that we’re seeing in our country today.”

Yet it was predictable that the left—once they had tired of gloating hideously over Charlie’s murder and then claiming (without a shred of evidence) that his assassin was in fact to the right of him politically—would immediately turn Trump’s argument on its head, accusing him of instrumentalizing the event, as Hitler used the February 1933 Reichstag fire, to move America a step closer to dictatorship.

On Constitution Day, we are all obliged to remember Benjamin Franklin’s reply to the lady who asked him on this day in 1787, “Well, Doctor, what have we got a republic or a monarchy?” “A republic,” Franklin replied, “if you can keep it.”

The source of this famous quotation is the journal of James McHenry, an Irish-born Maryland delegate to the Constitutional Convention, who had served under Lafayette at the Battle of Yorktown and later was secretary of war under presidents Washington and Adams. The woman who asked Franklin the question was Elizabeth Willing Powel of Philadelphia, whose father, brother and husband all served as mayors of that city.

Well, can we keep it? Are we losing it?

My benchmark, ever since Trump emerged as a plausible presidential candidate ten years ago, is Buzz Windrip. In It Can’t Happen Here (1935), a bombastic Democratic Senator—Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip, modeled on Huey Long, the populist Louisiana governor—is elected president, overthrows the Constitution, and institutes something a lot like an American Nazi regime, complete with paramilitary thugs (“Minute Men”), a Goebbels-like sidekick, and “Corpo” economics. Resistance comes only from a motely band of conservative Republicans and libertarians like the Vermont newspaper editor, Doremus Jessup, who is the book’s hero.

American literature has produced other and better-written fascist dystopias: Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) and Philip Roth’s Plot Against America (2004), to name just two. The early Cold War produced the alternative dystopia of a Stalinist totalitarianism. Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953) describes a world where the state has banned all books and routinely burns any that it finds. But Donald Trump is the Buzz Windrip of liberal nightmares.

Sullivan likens President Trump to “a wild boar—psychologically incapable of understanding anything but dominance and revenge, with no knowledge of history, crashing obliviously and malevolently through the ruined landscape of our constitutional democracy,” because he “cannot tolerate any system where he does not have total control.”

Trump may not have gone full Windrip in his first term, Sullivan concedes, but in his second term he has been unleashed. He can and does go after domestic opponents, from law firms to bureaucrats to journalists and judges. He has already declared states of emergency more than 30 times to justify extraordinary measures. He imposes tariffs with “zero constitutional or legal authority.” He has pardoned “violent rioters, insurrectionists, and corrupt pols on the take,” assaulted the autonomy of universities, ended free-speech protections for non-citizens, and mobilized “armed, masked, anonymous men and women” to round up and deport suspected illegal immigrants.

Kim Lane Scheppele, a professor of sociology at Princeton University, has echoed Sullivan’s alarm, citing Trump’s mobilization of the national guard to clamp down on urban crime as further evidence that America is on the road to dictatorship. The United States is “collapsing into some form of authoritarianism,” Harvard political scientist Steve Levitsky told the Guardian, where “abuse of power is so widespread, so systematic, and violations of law, violations of rights are so widespread and systematic that the playing field begins to tilt against the opposition. … And you would not call that a full democracy.”

Specific incidents—the FBI raid on the home of John Bolton, Trump’s former national security advisor turned critic, the replacement of Bureau of Labor Statistics commissioner Erika McEntarfer with E.J. Antoni, a Trump ally, the attempt to fire Federal Reserve governor Lisa Cook—are grist to the mill of such critics.

And yet there is a danger of impressionism in much of this commentary. “This week,” the Guardian solemnly intoned, “a giant banner was draped over the Department of Labor building, showing Trump glaring out over Washington DC above the slogan ‘American workers first.’” Wait, banners equal fascism?

Lionel Barber recoils from “the $200m State Ballroom which Trump has ordered to be constructed on the ground occupied by the east wing of the White House.” But where in the Constitution is there a prohibition on ballrooms?

Everyone suffering from Windrip Syndrome needs a reminder of what fascism was. In Italy, following the murder of the Socialist deputy Giacomo Matteotti in 1924 (almost certainly ordered by Mussolini) political opposition was suppressed. The likes of the Leninist Antonio Gramsci were consigned to prison. Henceforth, the National Fascist Party brooked no competitors. Newspaper editors were required to be fascists, and teachers to swear an oath of loyalty. Parliament and even trade unions continued to exist, but as sham entities, subordinated to Mussolini’s dictatorship.

German National Socialism emerged from the Depression, as opposed to the sustained expansion the United States has experienced in the past decade. It was explicitly revolutionary—the stated goal was to overthrow the Weimar system and create a racially pure Volksgemeinschaft. Party agencies such as the SA systematically used violence against opponents. Soon after Hitler came to power in 1933, the new regime began exerting direct control over the civil service, the media, the police, and the military.

Rearmament became the goal of economic policy and war the goal of foreign policy. From the outset, antisemitism was core feature. Above all, the Third Reich was from the outset a lawless regime. Just think of the arrests without trial—26,000 people were already in so-called “protective custody” as early as July 1933—and the summary executions, beginning with the Night of the Long Knives in June 1934, when between 85 and 200 people were murdered in cold blood.

Another historical reminder: the “imperial presidency” long predates Trump. Franklin Roosevelt’s critics saw the New Deal as a power grab by the executive branch. Richard Nixon’s Democratic critics, notably Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., made similar arguments in 1973. As Jack Goldsmith of Harvard and the Hoover Institution has argued, there has been a sustained “escalation of power grabs” by the presidency throughout this century, “aided by … substantial delegations of power from Congress and an approving Supreme Court.”

George W. Bush greatly enlarged the power of the U.S. national security state after the 9/11 attacks, 24 years ago this month. Barack Obama used executive orders for “large-scale and sometimes legally dubious policy initiatives,” asserted broad nonenforcement discretion in cases involving immigration, marijuana, and Obamacare, and used “legally dubious threats to yank federal funds from universities” to force changes to their rules on sexual assault and harassment—changes that had many malign consequences.

Joe Biden not only abused the presidential power of pardon for the benefit of his own errant son, amongst others. He extended the Supreme Court’s unitary-executive case law to fire the statutorily protected commissioner of the Social Security Administration. He purged Trump appointees from arts and honorary institutions, the Administrative Conference of the United States and the Department of Homeland Security Advisory Council. And, of course, the Biden administration had no qualms about waging or encouraging “lawfare” against political opponents, not least Trump himself.

In recent months, there has been a crescendo of complaint about the Trump administration’s alleged undermining of the Federal Reserve’s independence. However, as Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent argued in an important article published earlier this month, it is the Fed that has been overreaching in the years since the global financial crisis. A “gain-of-function monetary policy experiment” (quantitative easing) boosted wealth inequality much more than growth, then caused a nasty bout of inflation in 2022, and may end up costing taxpayers billions. The Fed has overreached on regulation, too. And its politicization—judged by the political donations of Reserve Bank directors—dates back ten years.

Yes, since his second inauguration Trump has cited emergency powers in around three dozen orders and memoranda. But both Obama and Biden did the same thing; they just did it more slowly. In any case, the law courts are currently grappling with close to four hundred cases involving the Trump administration.

According to the website Just Security, of 404 cases, none has been closed in favor of the plaintiff, 28 have been blocked, 82 temporarily blocked, 19 blocked pending appeal, 20 temporarily blocked in part; 48 have had a temporary block denied in part or wholly, 33 are pending appeal, 162 are awaiting a court ruling, 23 have been closed, two have been transferred, and just seven have been closed or dismissed in favor of the government.

This is Trump’s fifth year in government. I can assure you, that was not how German lawcourts worked in 1938, the fifth year of Hitler’s regime.

Representative Steve Cohen, a Democrat from Tennessee, has a website that tracks what he calls the Trump administration’s “Harmful Executive Actions,” from the closure of USAID to the sending of threatening emails to federal workers. The problem here is that Cohen conflates actions that are open to legal challenge and actions that are matters of policy he doesn’t like.

Goldsmith estimates that in around four dozen cases, the Trump administration has simply accepted court rulings against it, either by not appealing them in the first place, or by not pushing further after losing in courts of appeals.

As Jed Rubenfeld argues, the cases heading to the Supreme Court are doing so precisely because they are far from open-and-shut. The International Emergency Economic Powers Act may not be a secure basis for Trump’s reciprocal tariffs, as it confers on the president the power to “regulate” imports, not the power to tax them. That was the view of the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. But Section 338 of the Tariff Act of 1930 (the infamous Smoot-Hawley Act) empowers the president to impose tariffs of up to 50 percent on any country that is placing “any burden or disadvantage” on U.S. commerce. So the Supreme Court may side with Trump.

The Supremes may rule against Trump in the case of Lisa Cook, as it seems unlikely that a majority of the justices will accept the unproven allegations of mortgage fraud as sufficient “cause” sufficient for Trump to her from the Fed. They may also rule that the administration was acting illegally when it sank a boat allegedly carrying drug-smuggling members of the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua, or when it deported gang members on the basis of the Alien Enemies Act.

But the justices may back Trump on his right to send the National Guard to Los Angeles, Chicago, and Washington, DC. There are precedents for sending in the military to protect government officials carrying out their duties—in this case, agents of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

As Harvard Law’s Noah Feldman has pointed out, sooner or later the Supreme Court will have to make its mind up on these cases. Only if it calls every one of them in the administration’s favor will we need to start worrying that the separation of powers has stopped working.

In the same way, it is too early to write Congress off as a mere rubber stamp for the White House. The Republican majorities in Senate and House alike are wafer-thin. The economy is palpably slowing, partly because of tariffs, partly because of the drastic decline in immigration. Inflation is still well above the Fed’s 2% target.

Voters are thermostatic: they wanted immigration restriction back in November but are squeamish about deportations now that they see employees and neighbors rounded up and expelled. Despite the Democrats’ tanking approval and voter registrations, the GOP could still lose the House in the midterms in November next year.

There are informal checks on presidential power, too. The chief executives of some of the biggest tech companies seem embarrassingly eager to kiss Trump’s ring in return for minimal AI and crypto regulation, but not everyone is so sycophantic. Trump has plenty of vocal critics on both Wall Street and Main Street.

The same is true of the media. It’s hard to shut up the U.S. press corps, and the Internet has made the media even more unruly than in the past. I got into a Twitter argument with Vice President Vance earlier this year. As you can see, I am not yet in protective custody.

American generals also seem unlikely to support a U.S. monarchy, as there remains a very strong culture of military loyalty to the Constitution. As for the 1.3 million practicing lawyers in the United States, they all have a vested interest in preserving the rule of law. It’s their livelihood. I am sure our excellent General Counsel would agree.

The prelude to dictatorship is often civil war or anarchy. Americans may be polarized, but they are not at war with one another. I say this even after recent events that seem calculated to increase the risk of civil strife: not only the assassination of Charlie Kirk but also the fatal stabbing of Iryna Zarutska, a 23-year-old Ukrainian refugee, in Charlotte, North Carolina, on August 22, 2025. The man accused of killing her, an African American named Decarlos Brown Jr., had previously been arrested multiple times and convicted of robbery with a dangerous weapon, breaking and entering, and larceny. After the attack, he said simply: “I got that white girl. I got that white girl.”

If a hostile foreign power intended to destabilize American politics—and I can think of at least three who do—the killings of Charlie and Iryna would be perfectly crafted to that end, one crime exacerbating political division, the other racial mistrust.

Ladies and gentlemen: As in the 1930s, when Sinclair Lewis dreamt up Buzz Windrip, there are many in the 2020s who are emotionally over-invested in the idea of an American descent into fascism. It would be naïve to dismiss the fear that—especially in the febrile atmosphere occasioned by two such shocking murders—the presidency will grow yet more powerful relative to the other branches of government.

But the serious student of history knows that the United States today is a very long way from Italy in 1927 or Germany in 1938. And now, as then, it seems much more likely from a geopolitical standpoint that the United States will end up in conflict with the truly authoritarian regimes than fighting alongside them.

I say this with some feeling, having seen just what a real fascist government is capable of in the streets of Kyiv last weekend. By a bitter irony, the street where I saw an apartment building destroyed by a Russian cruise missile—which killed 23 innocent Ukrainian men, women and children—was named Václav Havel Boulevard.

Havel personified the spirit of freedom that ultimately freed Central Europe from Soviet tyranny. We should all remember his injunction, written when he was a dissident in Prague shortly before he was sentenced to five years in jail, to “live in truth.”

As events after Pearl Harbor showed, there is nothing like fighting real fascists and real imperialists to rekindle that American love of liberty Gray Gordon crooned about. Events in the world today remind us that freedom is under threat not just at home from illiberal ideologies and their proponents, but also abroad from the Axis of Authoritarians—China, Russia, Iran and North Korea—which pose lethal threats to democracy not only in Ukraine, but also in Israel and Taiwan. I find it hard to believe that we Americans will stand idly by if the authoritarians look likely to snuff out freedom in any of those embattled countries.

Charlie Kirk—who dedicated his life to debate and died with a mic, not a knife, in his hand—personified that innate American love of liberty.

We at UATX stand with Charlie. We stand for liberty and for truth.

In our own small way, we are trying to do what the men of 1787 achieved so magnificently—and they were all men, I’m afraid, even if it took a woman to ask Ben Franklin the crucial question.

We are daring not just to think, but to build. And we are building in the belief that, with the right system of governance—the right operating system, if you like—what we are building can endure, just as the United States has endured.

Next year, we shall celebrate the passage of a quarter of a millennium since the Declaration of Independence. It will also be five years since our own declaration of academic independence in November 2021.

It should by now be clear to you that we cannot flourish if the American republic—and, for that matter, the state of Texas—do not flourish, too. The constitution of academic liberty depends for its survival on the constitution of liberty at the federal and state levels.

There is no doubt in my mind that the constitutional order is threatened by malevolent adversaries, both at home and abroad. It is also threatened by those on the right who sometimes forget that the First Amendment protects “hate speech,” too.

But all that was also true in 1787. That was why Franklin used the words: “A republic, if you can keep it.” We have created a free university, dedicated not to the imposition of egalitarianism—as our president rightly said at our Convocation—but to the preservation of liberty, and to the fearless pursuit of truth on the basis of that liberty.

A university of liberty, ladies and gentlemen—if you can keep it!

WWSG exclusive thought leader Sir Niall Ferguson is one of the world’s foremost historians of economics, international relations, and global power. His incisive analysis illuminates the geopolitical forces and economic undercurrents shaping the 21st century. From great power competition to emerging security challenges, Ferguson offers unparalleled historical context and strategic insight — helping global leaders, policymakers, and business executives anticipate what lies ahead. To invite Sir Niall Ferguson to your next event, contact WWSG.

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson review

(Evening Standard) – From plagues and volcanic eruptions to the current Covid pandemic, mankind has always been faced with catastrophes.

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

Time to end secret data laboratories—starting with the CDC

The American people are waking up to the fact that too many public health leaders have not always been straight with them. Despite housing treasure…

Thought Leader: Marty Makary

One reason so many are quitting: We want control over our lives again

The pandemic, and the challenges of balancing life and work during it, have stripped us of agency. Resigning is one way of regaining a sense…

Thought Leader: Amy Cuddy