Time to end secret data laboratories—starting with the CDC

The American people are waking up to the fact that too many public health leaders have not always been straight with them. Despite housing treasure…

Thought Leader: Marty Makary

It’s a testimony to the sheer unpopularity of Keir Starmer’s government that only three months after voters gave the Conservatives their biggest electoral kicking in two centuries, Labour has already lost its polling lead. Indeed, it has achieved this so quickly that its opponents still don’t even have a leader.

But as much as Labour has failed to impress, its dire poll numbers reflect a wider trend across the western world, where political leaders are now roundly hated almost everywhere. This suggests something more profound is going on.

If politicians are disliked, it’s in part because western countries are so badly governed, although Britain seems especially so. Our cities are overcome with squalor; crime is higher than it needs to be; housing is in crisis; public services are in a dismal state; energy costs are too high and we are at the mercy of a planning system that immiserates us. It is evident across the West that the status quo is not working, and we are at a 1970s-style moment of crisis for the consensus.

The biggest of these problems is immigration. The current system is not making us richer or safer, and not only are current migration numbers deeply unpopular, they also erode the legitimacy of democracy, which depends on the idea of a people with a shared sense of identity and history.

The Conservatives have, in every election manifesto, promised to reduce numbers, and the most recent version of the Tory regime lost the faith of voters with a cynical immigration policy of ‘human quantitative easing’. To win back that trust, they will need a fresh start with a leader plausibly distant from past mistakes – and the only person who can do that is Robert Jenrick.

It was Jenrick who, as immigration minister, fought his own government over this issue and ultimately succeeded in reducing numbers. Then, frustrated by the government’s inability to honour its promises to the electorate, he took the decision to resign. His disappointment was shared by millions of former supporters who lost faith in the party and need to be won back. Trust in the Conservatives over immigration has evaporated, and Jenrick’s record makes him best placed to win back voters from Nigel Farage’s party.

Polling suggests that Tory-to-Reform switchers are the hardest to convince, but it’s a false premise that the party has to choose between regaining defectors from Reform or the Liberal Democrats. Immigration is a major concern among Lib Dem switchers too, and those deserters are just as socially conservative as the ones who stayed.

Many Blue Wall former Tories were hostile to Brexit – ‘Eurosceptics’ who nevertheless saw leaving the EU as unwise. They dislike Farage’s populist vibe but, like millions of voters, they support what the media calls a ‘far-right’ policy on immigration, when it is presented respectably and humanely.This is already happening on the Continent, as immigration undergoes a ‘respectability cascade’ and sensible-sounding politicians who resemble characters from Borgen articulate views which were seen as unthinkable a few years ago. Poland’s Blairite government has already temporarily suspended asylum, and it won’t be the last. Jenrick has grasped that the consensus is shifting. It is why, unlike Kemi Badenoch, he has made firm promises to limit numbers while also aiming for a strategy of avoiding needless provocation.

The moment of crisis goes beyond immigration, however, and relates to a system in which authority has slipped away from democratically elected lawmakers and towards arm’s-length bodies, judges and activists, whose power to frustrate government policy in immigration, energy or criminal justice is embedded in law.

While Badenoch is a formidable character, my impression is that she sees the problem as related to culture, while Jenrick views the system itself as the issue. This in part explains why Badenoch is so willing to engage in disputes over issues of identity, such as her spat with the former Doctor Who actor David Tennant, which I think is unhelpful. Contrary to what is often said, culture can be downstream of politics: change the system, and you change the culture.

Central to this is Jenrick’s pledge to leave the European Convention on Human Rights. Unless we leave, it will be impossible to reduce the record number of unvetted illegal migrants. The government has no means to halt their arrival, and has signalled its failure by booking more hotel capacity. The numbers will continue to rise as the developing world goes through a population bulge.

The existing rules make it impossible for politicians to run a system that earns the faith of voters. Only recently, a convicted killer from Albania won the right to stay in Britain. It was one of numerous examples where the state has been unable to enforce the law and the border. In many cases, the failure has led to the murder of British citizens.

The question of ‘who governs Britain’ is as important today as it was in the 1970s. The human rights debate is not simply about living ‘under the rule of law’ or not – it is a trade-off between the rights of citizens and non-citizens, as all positive rights are. But the ECHR is part of a wider debate about how ‘the rule of law’ and ‘human rights’ are a cover for a specific political programme. It is one where alternative solutions are declared impermissible while genuine rights are eroded, turning Britain into a country where people are thrown into jail for private messages and jokes.

Labour partisans will present any change to the status quo as extreme, because they understand that natural Tories are unnerved by radical change. But they fail to appreciate that politics itself – and the world – has changed. The average British voters don’t want social upheaval: they want cheaper housing and energy costs, greater civility and less crime, better public services and effective border controls – and they know that the current system isn’t delivering these things.

What set Margaret Thatcher apart from so many other Conservatives in the 1970s was that she had read Friedrich von Hayek. In Richard Cockett’s Thinking the Unthinkable – his indispensable account of the intellectual origins of Thatcherism – he describes how Thatcher used to pull a copy of Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty out of her handbag, declaring, ‘This is what we believe.’

Charles Moore shows in his definitive biography just how widely Thatcher read in the period before she became prime minister. Karl Popper, Frédéric Bastiat, John Maynard Keynes, Edmund Burke, Joseph Schumpeter, Alexis de Tocqueville, Alfred Marshall, C.S. Lewis, Adam Smith and Rudyard Kipling – all were quoted in her speeches after she had done the requisite homework.

In preparing for a single speech in 1977, Thatcher read and annotated articles by Shirley Robin Letwin, P.T. Bauer, Milton Friedman, Samuel Brittan, Robert Skidelsky, Hayek, Alan Walters and Paul Johnson. When was the last time a Tory leader chose Dostoevsky’s The Possessed and Koestler’s Darkness at Noon as ‘holiday reading’?

When I first got to know Kemi Badenoch, I realised at once that she was cut from the same cloth. Four-and-a-half years ago, in anticipation of a trip to California, she wrote to me to ask a favour. The standard ask by British politicians visiting the Bay Area is for a meeting with one of the masters of the technological universe. (‘Do you know Peter Thiel and/or Marc Andreessen?’) This was different: ‘You wouldn’t by any chance know Thomas Sowell personally would you? He is probably the biggest reason I am a Conservative MP today and probably my last surviving hero. I am feeling very guilty that I postponed every opportunity to meet Roger Scruton when I had the chance and now it is too late! Don’t want to repeat the mistake.’ That got my attention.

Tom Sowell is less well known in the UK than he deserves to be. At the Hoover Institution and among American conservatives more generally, he is a legendary figure. Born in segregated North Carolina and raised in hard-knocks Harlem, Sowell is now the grand old man of conservative economists. His being black is important, but not the most important thing about him. He was one of that extraordinary generation of free-market economists trained at the University of Chicago after the war. In a prolific career, he has made the case against minimum wages, affirmative action and many other misconceived progressive policies. His most recent book, Social Justice Fallacies, is a tour de force.

Now aged 94, Sowell is more or less a recluse, and to my embarrassment I failed to get Badenoch the meeting she sought. But the fact that she credits Sowell with making her a Conservative MP is all the reason any Tory party member should need to vote for her.

I have nothing against Robert Jenrick. I have never met him. I have never read him. But that is the point. Jenrick is such an archetypally uninspired Tory frontbencher that he’s earned the nickname ‘Robert Generic’, whereas Kemi has convictions. She has principles. This is hard for some people to take. ‘She doesn’t suffer fools gladly,’ I have heard it said. She has ‘sharp edges’ and ‘rubs people up the wrong way’. It is astonishing to me that any British Conservative could regard any of these qualities as demerits. They are the things the party establishment said about Thatcher even after she, Hayek in her handbag, had won them three consecutive general elections.

Of course, 2024 is not 1979. The challenges Britain faces today are not the same ones we faced on the eve of the Thatcher era. But they are not completely different either. The economy has been performing worse than peer economies for most of the past decade – just as was true in the 1970s. Inflation has been more of a headache than elsewhere – as in the 1970s. Public finances are in a dire state – rather worse than in the 1970s in fact. And the entire country feels run down, the result of decades of under–investment in housing, transport and energy infrastructure. That, combined with an increase in population largely due to substantial net immigration, explains the mood of malaise that afflicts modern Britain.

What is different is that because of immigration, we are a much more racially mixed country than we were 45 years ago. And that is why Badenoch would pose such a formidable threat to the Labour government if she were to be elected Tory leader. We British are not, despite our reputation in the New York Times, mired in nostalgia for the imperial past. It should come as no surprise that we could soon have Europe’s first black female leader – and that she is a Conservative.

Badenoch has been an effective opponent of ‘critical race theory’, arguing that ‘adherents to this modern creed do not think in terms of individuality and personal responsibility, freedom of association or expression and shared experiences, but separated, segregated identities of victims and oppressors’.

But being black is not the most important thing about Badenoch. Like Thatcher, she is middle-class, the daughter of professionals. Like Thatcher, she studied a hard subject at university (computer systems engineering) and came to political and economic theory later in life, after experiencing the real world of the private sector.

Like Thatcher, Badenoch is a free–trader in a world of tariffs, as she made clear in a speech on trade at Chatham House in March in which she strongly opposed ‘hosing industries down with subsidies or slapping tariffs on products from abroad’. Like Thatcher, she is also keenly aware of the threat posed to liberty by an increasingly aggressive Communist superpower.

Best of all, from my point of view, is her sense of history. One of the books that has influenced her thinking is Daron Acemoglu and Jim Robinson’s Why Nations Fail, which makes the point that Britain’s spectacular rise in the 18th and 19th centuries owed more to constitutional constraints and the rule of law than to (as she put it) ‘colonialism or white imperialism or privilege or whatever’. That is a fundamental argument not only about Britain’s past, but also about its future, which will be prosperous only if we return our government to the principles that Badenoch holds dear.

A country adrift needs a leader with conviction. We are lucky to have her.

Time to end secret data laboratories—starting with the CDC

The American people are waking up to the fact that too many public health leaders have not always been straight with them. Despite housing treasure…

Thought Leader: Marty Makary

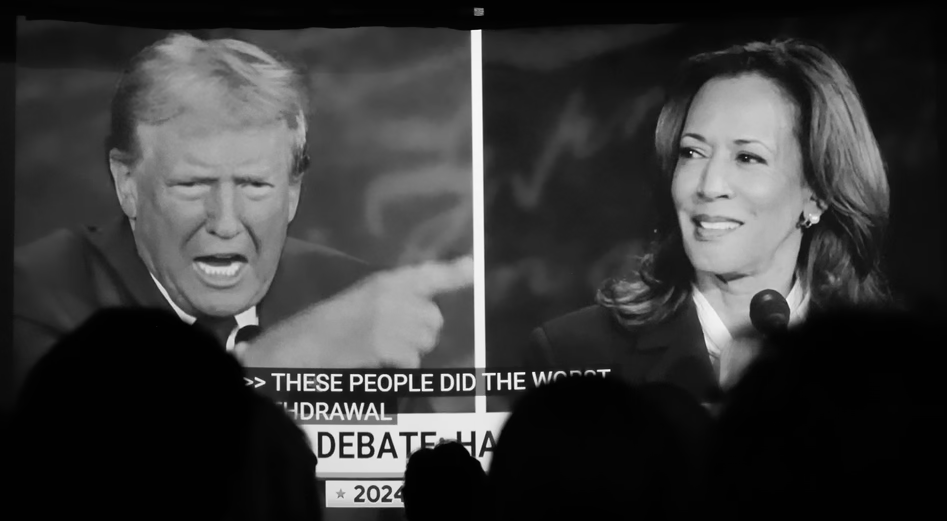

David Frum: How Harris Roped a Dope

This piece is by WWSG exclusive thought leader, David Frum. Vice President Kamala Harris walked onto the ABC News debate stage with a mission: trigger…

Thought Leader: David Frum

Michael Baker: Ukraine’s Faltering Front, Polish Sabotage Foiled, & Trump vs. Kamala

In this episode of The President’s Daily Brief with Mike Baker: We examine Russia’s ongoing push in eastern Ukraine. While Ukrainian forces continue their offensive…

Thought Leader: Mike Baker