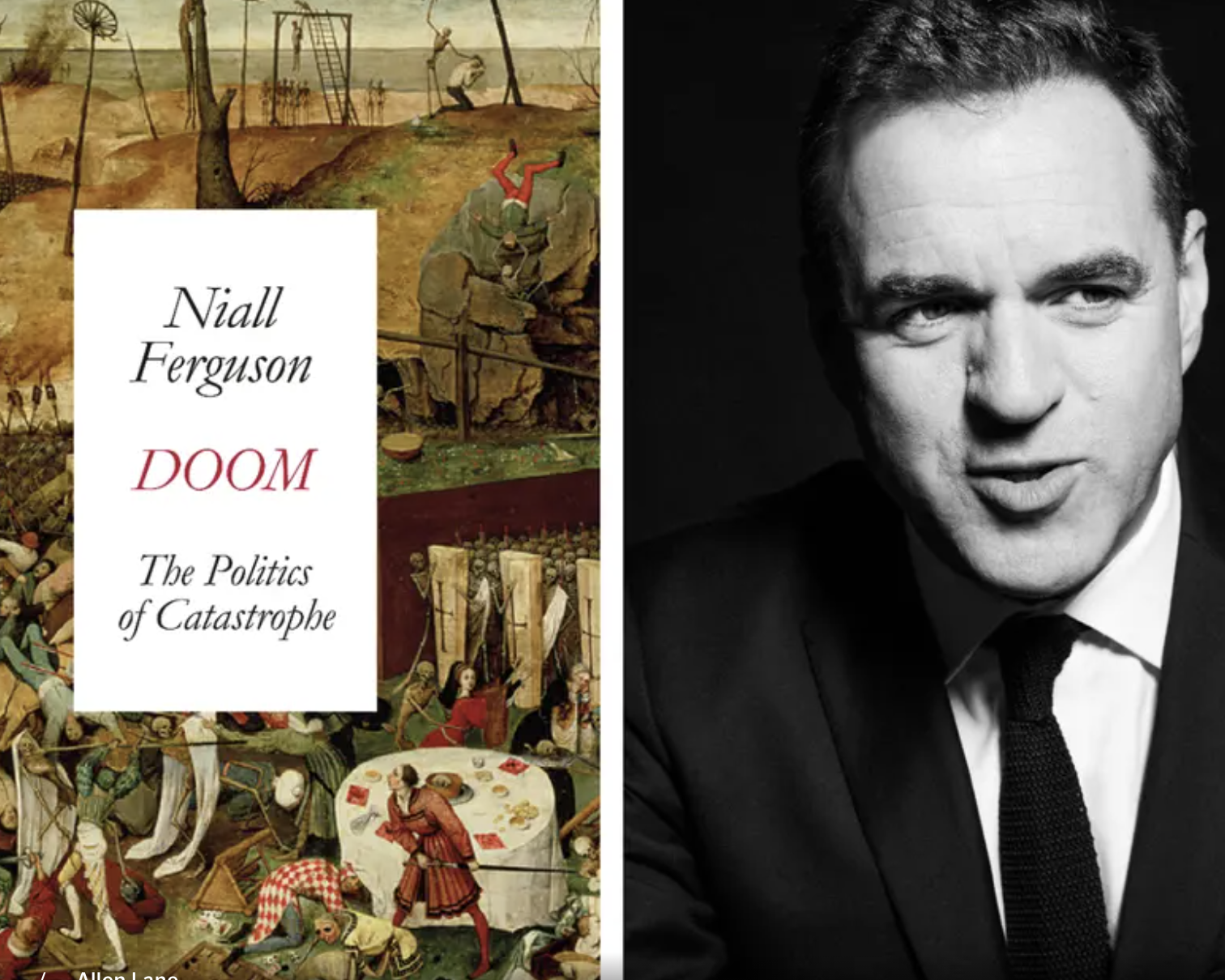

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson review

(Evening Standard) – From plagues and volcanic eruptions to the current Covid pandemic, mankind has always been faced with catastrophes.

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

Of all the powers of the presidency, none comes more naturally to Donald Trump than weaponizing America’s economic might.

Since returning to the White House, he has ordered sweeping tariffs on China, Canada and Mexico and threatened a barrage of sanctions and levies on everyone from Colombia and Russia to the European Union and the BRICS.

Trump’s second term is shaping up to be a turbocharged version of his first, when he styled himself “Tariff Man” and brandished a “Game of Thrones”–inspired poster warning “Sanctions Are Coming.” Then, as now, his actions matched his rhetoric: He slapped tariffs on China, cut microchip exports to Huawei and launched “maximum pressure” campaigns against Iran, North Korea and Venezuela. He imposed nearly as many sanctions in four years as Barack Obama did in eight.

Back then, retaliation was muted. America still inhabited a world akin to the dawn of the nuclear age in the 1940s: It possessed fearsome economic weapons, but no one else did. Today, the world looks very different. Many countries are prepared to fight back. The risk of a rapidly escalating global economic war is high—and America is poorly equipped to prevent it.

This economic arms race began in response to Trump’s first-term policies and accelerated with the Biden administration’s sanctions and export controls on Russia and China. But it also reflects a deeper tension: The global economy was designed for the benign geopolitical environment of the 1990s, not for the more dangerous one that exists today. As great-power competition has intensified, integrated supply chains and financial markets—once viewed as anchors of stability—now seem like glaring vulnerabilities. They include chokepoints that Washington, Beijing and other capitals can exploit in a multi-front economic war.

No country has devoted more energy to this contest than China. When Trump launched a trade war during his first term, Beijing was unprepared. Its counterstrategy—imposing reciprocal tariffs on American goods—ran into a hard limit: China imports far less from the U.S. than the U.S. imports from China. Beijing simply had less room to escalate, leading Trump to conclude that “trade wars are good, and easy to win.”

But China learned its lesson. In the years since, it has built its own arsenal of economic weapons. It has enacted a raft of new laws that give it the power to impose penalties ranging from targeted sanctions to full-fledged embargoes. And it has painstakingly mapped out global supply chains, identifying chokepoints it can weaponize with devastating effect. Beijing is now poised to respond to U.S. measures asymmetrically—not by mimicking Washington’s actions but by hitting America where it hurts.

We got a taste of these capabilities days before the 2024 presidential election, when China cut off Skydio, America’s largest drone company, from vital battery supplies. Skydio was forced to ration batteries, limiting them to one per drone. The consequences rippled far beyond Silicon Valley: The Ukrainian military relies on the company’s drones to gather battlefield intelligence and document war crimes. “This action makes clear that the Chinese government will use supply chains as a weapon to advance their interests over ours,” said Skydio CEO Adam Bry, who called it “an attempt to eliminate the leading American drone company.”

China has other chokepoints it can manipulate, starting with critical minerals. The country produces two-thirds of the world’s graphite, lithium and cobalt—essential for electric vehicles—and dominates the global supply of rarer minerals like gallium, germanium and antimony, which the Pentagon depends on for radar systems and precision-guided munitions. In recent months, antimony prices have more than doubled as China introduced export controls, leaving the U.S.—which hasn’t produced antimony since the 1990s—perilously exposed. It’s telling that China’s initial reaction to Trump’s new levies was not limited to tariffs but included export controls on tungsten and other key minerals. America has many more supply-chain vulnerabilities, including some that officials and business leaders have yet to fully appreciate.

By contrast, China has been actively fortifying its economy against external pressure. Scarred by curbs on access to American microchips, China has poured money into its domestic semiconductor industry, investing several times more than the U.S. has under the CHIPS Act. It has exploited loopholes in U.S. export controls to amass vast stockpiles of semiconductor equipment. And it has built a homegrown alternative to the SWIFT network to reduce its reliance on the U.S. financial system. These defensive measures won’t make China invincible, but they could blunt the impact of any new sanctions and embolden Beijing to retaliate more aggressively.

Other rivals have similarly beefed up their economic warfare capabilities. Russia has weaponized natural gas exports to Europe, and it recently restricted sales of nuclear fuel to the U.S. Despite a new law that encourages domestic sourcing, American nuclear reactors still depend on Russia for about a quarter of their fuel. As the artificial intelligence race heats up, tech firms such as Microsoft and Google are counting on nuclear energy to power the data centers that train advanced AI models—a bet illustrated by Microsoft’s deal to reopen Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island facility. Yet these plans could be jeopardized if Moscow permanently bans nuclear fuel shipments.

Russia is also spearheading an effort to weaken the dollar’s role as the default currency for international payments, which underpins the potency of American sanctions. At last fall’s BRICS Summit, Moscow unveiled a series of initiatives to help bloc members bypass the dollar entirely in their trade with one another.

A common BRICS currency is a pipe dream, but a platform allowing members to settle trade using their own digital currencies is much more plausible. In fact, a similar project called mBridge, led by the central banks of China, Thailand, the U.A.E. and Saudi Arabia, proved its ability to settle payments in mere seconds late last year. Trump’s threat of 100% tariffs against the BRICS countries if they create a shared currency misidentifies the challenge. The real issue is that Russia, China and their partners are building parallel systems that—left unchecked—could defang U.S. financial power.

It isn’t just adversaries who are gearing up for economic war. Allies are doing the same. Japan recently appointed a cabinet minister for economic security, and the EU and Britain have drastically enhanced their ability to impose sanctions.

Under the Biden administration, the U.S. encouraged these efforts, working with G-7 allies to lay the foundations of an economic security alliance. But all this progress could come undone if Trump wields sanctions and tariffs against our friends, as his targeting of Canada and Mexico—despite the announced one-month delay—shows he is prepared to do. Worse, instead of joining forces to confront China and Russia, our allies could even turn their revamped economic arsenals against the U.S. In Canada, the race to replace Justin Trudeau has already become a contest over who can deliver the most effective counterpunch to Trump’s tariffs.

With so many countries armed and ready, the challenge for Trump will be to use economic weapons to advance U.S. interests without leaving America isolated or ruining the world economy. As much as Trump values unpredictability and improvisation, they are a recipe for miscalculation and failure.

Here again, the nuclear age offers lessons. What has kept the peace in a world of multiple nuclear states isn’t bluster or brinkmanship but institutions, doctrine and diplomacy. Formally established in 1947, the Joint Chiefs of Staff unified decision-making across military branches, creating a system that could manage the complexities of nuclear competition. The strategy of mutual assured destruction deterred aggression by guaranteeing that any nuclear attack would bring total annihilation for all sides. And international agreements like the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty set clear rules and built trust to limit the spread of nuclear weapons.

We have none of these resources to guide us through today’s Age of Economic Warfare. Authority over sanctions, tariffs and export controls is scattered across multiple agencies, with no one empowered to craft an overarching strategy. We have no doctrines for economic warfare, nor do we have treaties outlining rules and norms. That is why, even when Trump hasn’t been in the White House, the U.S. has often pursued haphazard policies, with decidedly mixed results. If Trump wants to use his favorite weapons effectively, he should start by creating an economic war council to address this problem and develop a coherent strategy.

But if Trump continues on his current course—wielding sanctions and tariffs indiscriminately, against adversaries and allies alike—he risks triggering a vicious cycle of retaliation that fractures the global economy. As supply chains unravel, prices will rise, scarcity will return and our standard of living will suffer.

Painful as that will be, the geopolitical consequences could prove even worse. We originally embraced economic interdependence not only as a path to prosperity but also as a way to prevent war. If states can’t secure resources and markets through trade, the temptation of conquest and imperialism will surge. Great powers could once again find themselves drawn into military conflicts.

If we mishandle them, today’s economic wars could become tomorrow’s shooting wars.

Edward Fishman is a senior research scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy. His new book, “Chokepoints: American Power in the Age of Economic Warfare,” will be published by Portfolio on Feb. 25.

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson review

(Evening Standard) – From plagues and volcanic eruptions to the current Covid pandemic, mankind has always been faced with catastrophes.

Thought Leader: Niall Ferguson

Time to end secret data laboratories—starting with the CDC

The American people are waking up to the fact that too many public health leaders have not always been straight with them. Despite housing treasure…

Thought Leader: Marty Makary

Sanjay Gupta: There are still key questions about Trump’s injuries after attempted assassination

This piece is by WWSG exclusive thought leader, Sanjay Gupta. It’s been five days since gunfire erupted at Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump’s rally in…

Thought Leader: Sanjay Gupta