Guest Post by Paul Nicklen | Seeing the Pod for the Narwhals

This is a guest post by WWSG exclusive speaker, Paul Nicklen.

Sometimes the wide-angle view reveals the big picture in ways that a close-up can’t.

“It is not so much for its beauty that the forest makes a claim upon men’s hearts, as for that subtle something, that quality of air that emanation from old trees, that so wonderfully changes and renews a weary spirit”.

– Robert Louis Stevenson

We have all had that moment when we are so involved in the details of something that we forget to see the situation as a whole.

This is especially true of wildlife photography, where spontaneity — being prepared for that unexpected moment, which can flash by in the blink of an eye, literally — counts for everything. When we are primed to spring into action at a moment’s notice, it’s all too easy to lose sight of the bigger picture.

Good images tend to be sharp and tightly focused on the subject at hand. Great images, though — the kind I am attentive to making and always hoping to achieve — demand context and perspective.

In the field, I try to consider every component of a composition, and that means taking in what lies just beyond the edges, not just what’s in the middle of the frame. Even if what lies at the edges doesn’t make it into the final print, it’s important that I know it’s there.

I call it ‘scanning the frame.’ I roll my eye around the entire frame and review each quadrant one after the other, starting at the bottom and working my way up the left side, then across the top and down the right. I ask myself, ‘Is this enchanting, majestic narwhal captivating enough on its own, or would including the crumbling sea ice just beyond the frame reflect the wider narrative about climate change?’

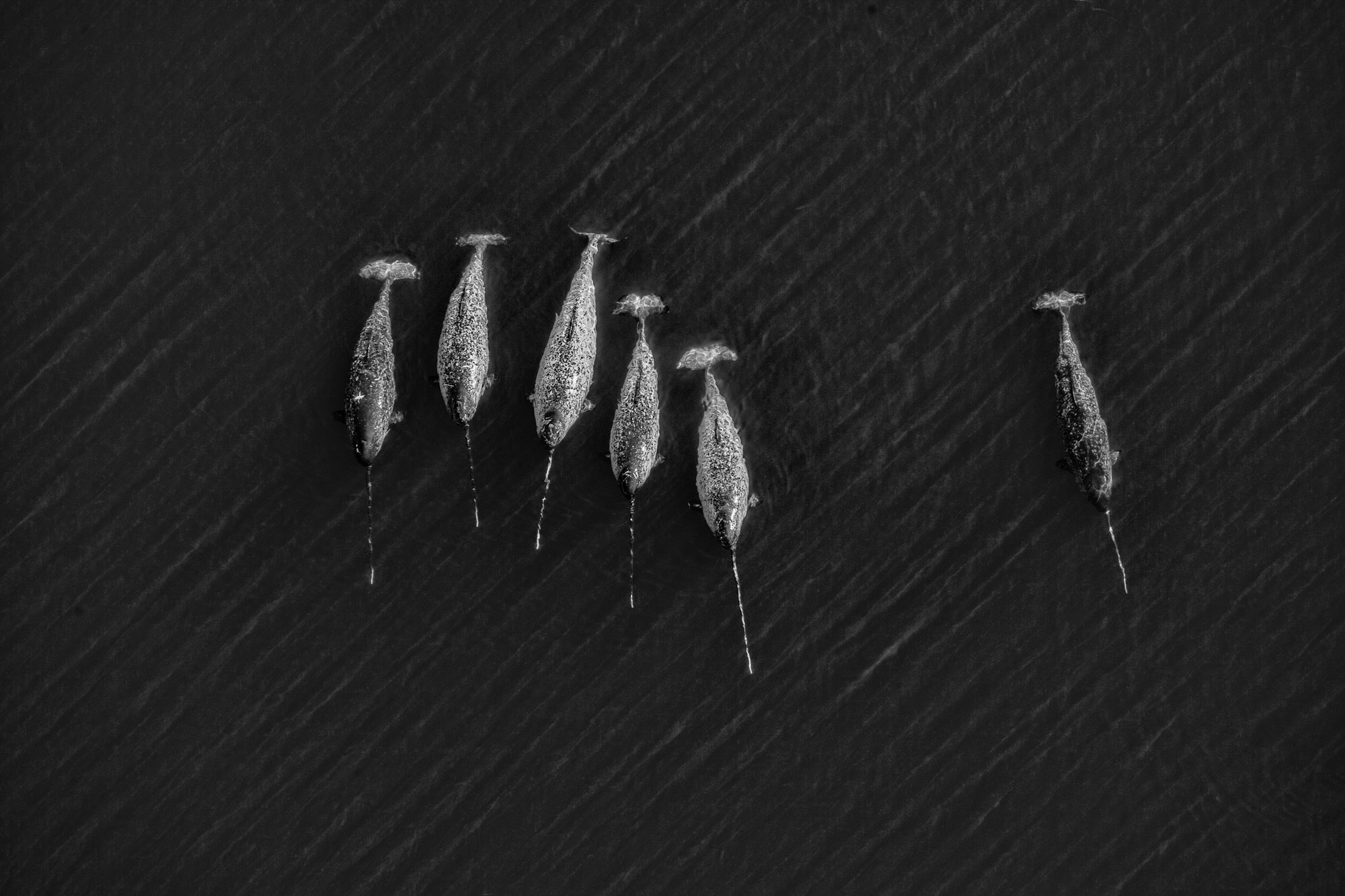

Narwhal migrations are rarely seen because they are out at sea in ice that’s breaking up — virtually impossible conditions for photography. The only real perspective you can gain is from the air, and I spotted the pod from the cockpit window of an ultralight airplane.

“Gathering of Unicorns”

My narwhal assignment for National Geographic several years ago provided as clear an example of this as any I can recall. After five years and more trips than I can remember to Nunavut’s ice edge, I finally spotted the pod of narwhals I had been dreaming about since I first pursued the idea of becoming a professional photographer.

I am always looking for opportunities to make my image more interesting, and that means inspecting the viewfinder for every minute detail while using my peripheral vision to look for context. I get the focus down as quickly as I can so that I know I have at least one image that is sharp as a tack, but then I slow down and look around the frame for things I didn’t notice at first glance.

My first instinct was to start photographing using a long lens — these crystal-clear, tight close-ups in which individual narwhals filled the frame, each one showing its own distinct personality, brought to life in vibrant colors and razor-sharp clarity. I knew instantly that they were good images, great even. This is one of the unique joys of nature photography — being there to capture that special moment you know few others have seen, let alone had the privilege to photograph.

What I did not realize, though, until I slowed down and considered my options, was that by zooming out and standing back, the entire perspective changed, and the picture changed with it. I could see entire groups of narwhals, where they formed more interesting — and unusual — lines, shapes, and patterns. It created an entirely different mood, visually and emotionally. I could see it happening in front of my very eyes.

Whether someone is flipping through the pages of National Geographic magazine or looking at a framed print on a gallery wall, I want that person to be instantly transported through that two-dimensional surface and become so immersed in that image that they have a powerful, visceral reaction. I want them to feel it.

f I’m photographing a scene, I’m analyzing it: I’m looking at the light, at various aspects of the frame, and examining everything. If I ever settled for looking at everything only with my left brain, then I wouldn’t be able to get lost in the moment. If I fail to lose myself in the moment — if I fail to find the wonder —then I can’t expect anyone else to feel that sense of wonder. Making great photographs is hard enough; we should do all we can to give ourselves a fighting chance. That day with the narwhals provided me with a lesson I have never forgotten.

With gratitude,