|

The Inuit have a culture of community and love, and it has been an honor to have been welcomed into their homes and invited to share their customs and way of life since I was a young child. Even as a kid growing up in Kimmirut, Baffin Island, it was considered rude to knock on a door and wait for someone to answer it. Every door in the community was open to every person, 24-hours a day. Some nights would be spent playing under the aurora borealis until 3am. Rather than returning home, I could stop in any house on the way home and grab some bannock or warm stew that would be sitting on the kerosene stove.

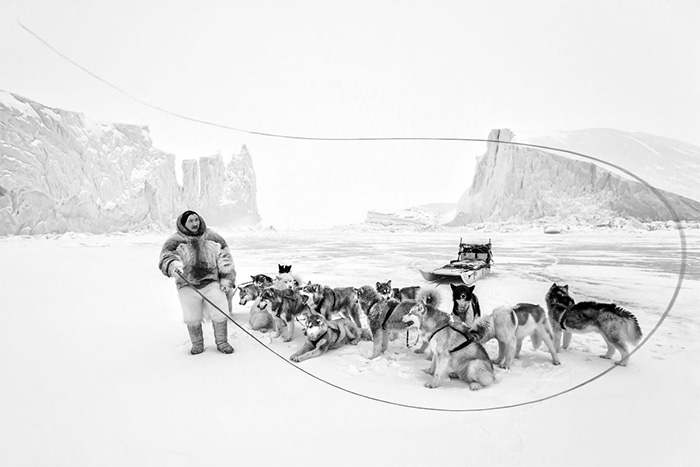

The most noticeable difference between Qaanaaq, Greenland, and the community I grew up in was the conspicuous absence of snowmobiles. I was four years old when my family moved to Baffin Island in Canada’s vast Nunavut territory. And while there are striking similarities — the low winter sun, the long dark nights in January and February, and the midnight sun in June and July — it is the contrasts that strike the senses.

The noise of engines — truck engines, power generators, snowmobile engines — make so much noise that, after a while, we no longer notice it. In fact, that was my dad’s expertise, to keep all of the diesel engines purring year round in the small northern outpost. Engine noise can startle and displace the wildlife Inuit hunters depend on to survive, though, so they opt for quieter, more traditional means of transportation, such as qamutiiks (Inuktitut for sleds) and qajaqs (Inuktitut for kayaks). Silence is golden. The silence of winter allows polar bears, caribou, Arctic foxes, and other alert animals to roam comfortably just beyond the outskirts of town. With sleds come sled dogs — huskies, in large numbers. The population of Qaanaaq is just 650 people, and yet it is home to more than a thousand dogs.

|